Goetheanum from West. Image © Wladyslaw Sojka via Wikimedia Commons

Goetheanum from West. Image © Wladyslaw Sojka via Wikimedia Commons

Share

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1032300/living-cycles-in-regenerative-architecture-lessons-from-the-goetheanum

As climate uncertainty and ecosystem changes reshape design priorities, architecture plays an increasingly active role in these discussions, rather than merely observing. Within this perspective, the idea of making a “re” encourages a conscious step back to rethink, reconnect, and realign the relationship between buildings and their environments. This approach, central to regenerative architecture, extends beyond specific technologies or scales, encompassing everything from master plans that aim to re-naturalize cities to national pavilions that combine art and science.

What is the way forward? On the one hand, many current discussions emphasize technology; on the other, there are approaches that, rather than being in opposition, complement one another and broaden the range of possibilities, drawing on tradition, ancestral knowledge, and a profound understanding of the environment. Among these perspectives, the work of Rudolf Steiner and the anthroposophical movement, developed in the early 20th century, offers a vision and insights that connect architecture with ecological rhythms, materials, and community life.

Rudolf Steiner was an Austrian philosopher, educator, and social reformer who founded the anthroposophical movement, a spiritual and philosophical system that seeks to understand the human being and the world through both scientific methods and inner insight. He promoted an integrative perspective in which the spiritual, the natural, and the human intertwine, resulting in design as a living process that harmonizes the built environment as an extension of the “whole,” shaping the surroundings in conjunction with the cycles and needs of nature and society. This vision intersects with biodynamic agriculture and regenerative architecture—both practices rooted in seasonal timing, respect for the land and its processes, and careful attention to the relationships that shape the environment.

Related Article Ecovillage Design: Models for Regenerative Urban Neighborhoods  Goetheanum 1920. Image © Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Goetheanum 1920. Image © Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

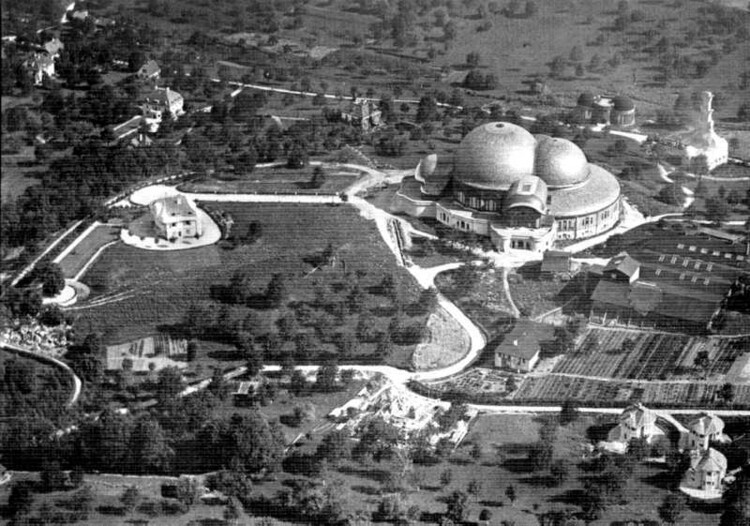

As an illustration of this philosophy, the Goetheanum—located in Dornach, Switzerland—may at first glance appear to be primarily a sculptural building. However, it embodies Steiner’s spiritual and artistic intent, his attunement to agricultural rhythms and materials, and a thoughtful approach to the experience of inhabiting a space. Built more than a century ago, it anticipates many concerns that today drive regenerative architecture: integration with the rural environment, attention to seasonal cycles, conscious use of resources, and a sensory approach to space.

When Anthroposophy Follows Form: Tracing the First and Second Goetheanum

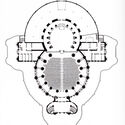

Between 1908 and 1925, Steiner designed 17 buildings, including the first Goetheanum, a wooden structure that, in its historical context, was a contemporary of the Bauhaus. However, while the Bauhaus promoted a functionalist and rationalist approach, the Goetheanum stood out for its ideas, which were relatively controversial at the time, along with its organic and expressive forms, reflecting the spiritual and holistic vision of Anthroposophy.

First Goetheanum. Image © Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

First Goetheanum. Image © Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

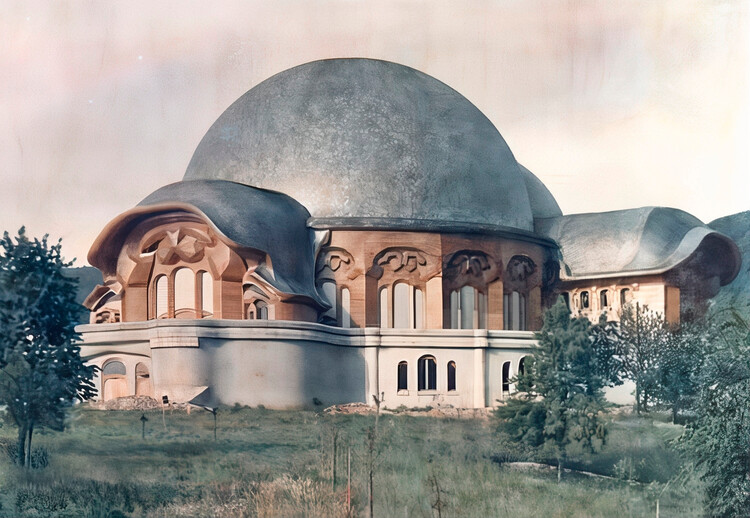

Referencing Johann Wolfgang von Goethe—renowned for his theory of the Metamorphosis of Plants—the two-domed building translates these ideas into an architecture that aims to create a coherent whole from interrelated organic forms. Steiner conceived his projects as constructions where each element evolved from an internal logic, engaging in dialogue with the materials, the surrounding landscape, and the people shaping it.

This approach led to collaborative work with artisans and artists, who incorporated wood and glass craftsmanship. In particular, wood carving played a central role: it was not seen simply as a construction act but as a process of excavating the material, producing an ensemble where materials and context are deeply intertwined.

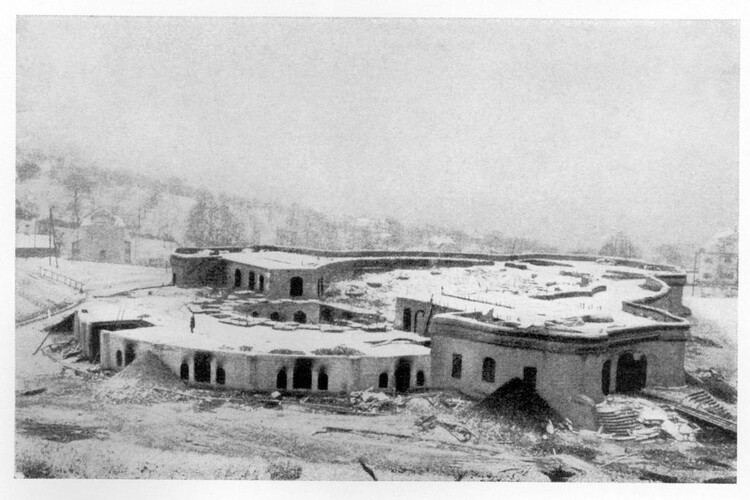

Ruins of the First Goetheanum. Image © Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Ruins of the First Goetheanum. Image © Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

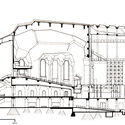

Also known as the Dornach Building, the first Goetheanum was destroyed by fire in 1922, just three years after its construction. However, by 1923, a second version was already under development. This new structure was made almost entirely of concrete, except for a few decorative wooden elements. Like its predecessor, Steiner stated that the building was to be conceived as an organic form, but not as an imitation of nature. Concrete, already explored in the outbuildings, now offered a different possibility: instead of excavating as with wood, artisans sculpted the material.

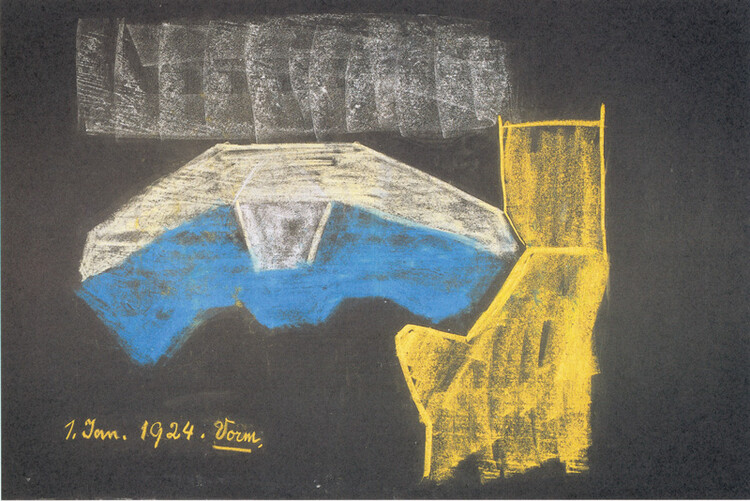

Blackboard drawing showing the idea for the second Goetheanum. Image © Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsLiving Cycles as Design Ethos: Lessons from the Goetheanum

Blackboard drawing showing the idea for the second Goetheanum. Image © Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsLiving Cycles as Design Ethos: Lessons from the Goetheanum

From the ideas carried over from the first building and integrated into the second Goetheanum, completed in 1928, a series of lessons emerges that, beyond their original context, resonates in contemporary discussions on regenerative design and rural ecology. It is not merely an architecture with symbolic or spiritual intent, but a construction that proposes new ways of relating to the environment, materials, and life cycles.

At the Goetheanum, architects conceive architecture not as an isolated object but as a living presence that engages with the rhythms of its surroundings. The building is situated within a rural landscape shaped by biodynamic agricultural practices, also pioneered by Steiner, and its design is attuned to the changing light throughout the day and year. Sunlight, filtered through colored-glass windows, illuminates watercolor murals arranged in a spectrum of greens, blues, violets, and pinks, creating an experience attuned to the daily and seasonal changes. Here, color does not merely embellish; it captures the tones of the landscape and becomes part of a broader sensory atmosphere.

Aerial view of Goetheanum. Image © Wladyslaw Sojka via Wikimedia Commons

Aerial view of Goetheanum. Image © Wladyslaw Sojka via Wikimedia Commons

This experience opens up the possibility of approaching architecture as an active ally to the cycles of the territory, rather than as a force aiming to dominate or deplete them. In settings where seasonal variation is a determining factor—such as floodplains, deserts, or subsistence agricultural regions—this approach calls for designing spaces that respond sensitively to environmental rhythms. The idea is not to build against nature, but to build with it.

- Building Place Through Shared Making and Material Know-How

In the Dornach building, materials are not used solely for their structural function. Wood, glass, and concrete were worked by hand by local craftsmen and artists, resulting in carved surfaces, engraved stained glass, and sculpted forms that express ideas extending beyond the technical. This way of building did not follow a fixed plan. Still, it unfolded as a collective process of experimentation and attentiveness, where craft and shared vision were as vital as Steiner’s proposed design. The materials thus became carriers of meaning, capable of conveying cultural, ecological, and symbolic connections.

Goetheanum, Great hall. Image © Wladyslaw Sojka via Wikimedia Commons

Goetheanum, Great hall. Image © Wladyslaw Sojka via Wikimedia Commons

The emphasis on craftsmanship, the scarcity of raw materials caused by World War I, and the use of non-industrial geometries—such as those in the windows—reflect a desire to build by hand, in dialogue with the environment and in rhythm with time.

This approach is especially fertile in rural environments, where vernacular knowledge and access to locally sourced materials are more prevalent. By thinking globally but building locally, architecture can reclaim indigenous practices and activate co-creation processes with communities, allowing each decision—from structural joints to finishes—to emerge from the dialogue between traditional techniques and contemporary needs. Recovering the artisanal dimension is not a nostalgic gesture, but a way for design to regenerate connections between people, territories, and resources.

Interior. Image Courtesy of desigboom

Interior. Image Courtesy of desigboom

This building—and, more specifically, Anthroposophy—while serving as a bridge between the sensible and the spiritual, opens up a broad field of analysis for exploring the relationship between the building process and the environment from multiple perspectives. Rather than separating the natural from the built environment, this vision understands them as inseparable parts of a single, interconnected whole.

From this perspective, meaningful intersections emerge with contemporary approaches, including horticulture, ecovillage design, and vernacular techniques. These movements, echoing the ideas developed at the Goetheanum, draw on Anthroposophy not as a utopian or nostalgic reference, but as a resource for rethinking rural life. They propose an experimental and ecological path—one that embraces the complexity of the territory, fosters co-creation with local communities, and seeks to restore deep connections between people, the land, and its resources.

Interior. Image Courtesy of desigboom

Interior. Image Courtesy of desigboom

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Regenerative Design & Rural Ecologies. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.