Great Barrier Island sits in the South Pacific Ocean, a 4½-hour ferry ride out from Auckland, New Zealand. In summer there are daily crossings, cut down to three a week in winter.

Named by Captain Cook, the volcanic island 62 miles away from the country’s biggest city, out in the Hauraki Gulf, now hosts a touch more than 1,000 people, up a few hundred in the past decade, most of whom live off the national grid. It has only one informal rugby club — the Bushpigs — who play one proper match per year. With not enough players to form age-grade sides, if you are a kid of any shape or size, you get chucked into the mixer.

This is where Jamison Gibson-Park’s story begins. The end, for now, will have the Barrier-born Irishman in a British & Irish Lions team at scrum half for the second Test against Australia at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in front of nearly 90,000 fans. It will be a little more high profile than the start of his journey.

“It was a fairly quiet upbringing, but I didn’t know any better at the time,” the No9 says. “I wouldn’t have had any official games, but ran around with 15-year-olds from two and three years old. It was just the way it was. You grow up quickly.

“It’s a pretty big island land-mass wise, but the population is small. It takes ages to get anywhere as the roads are sparse from top to bottom. I spent a lot of time in the water, on the beaches, rolling around in bare feet, on my bike.

“You can fly to Auckland from there, but it’s a small plane so I wouldn’t recommend it. I’ve had some dicey flights… far out. There’s a passenger ferry that runs for four months through summer, which takes two hours, otherwise it’s 4½ hours. It’s a bit of a trek, but it’s well worth doing.”

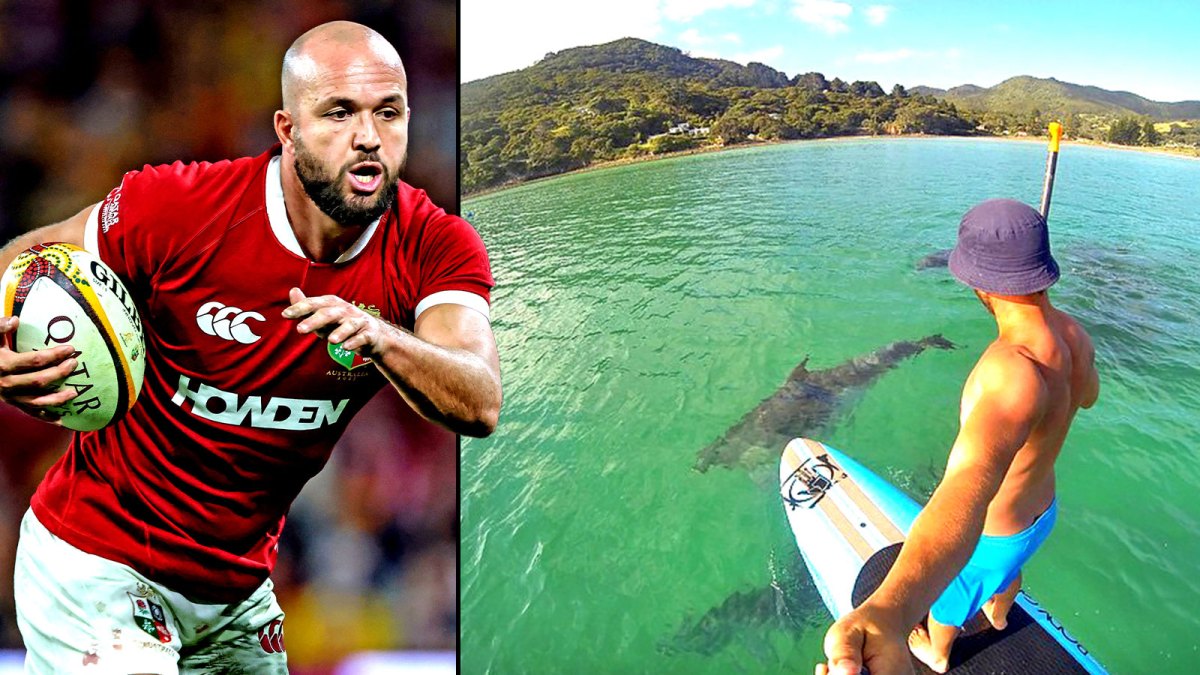

Gibson-Park posted this picture of himself paddle boarding in the company of dolphins on Great Barrier Island, which has a population of just over 1,000, in 2015

His mother, Tara, is the eldest of four daughters, so she wanted him to keep the Gibson part of her name when she married Billy Park and had children — hence the double-barrelled Jamison. Gibson-Park’s story is a little complicated as he has Maori heritage, from the Ngati Porou and Ngai Tai tribes, yet his mother’s family are from Armagh, Northern Ireland.

His journey from the island in the ocean to inspiring the sea of red Lions fans has been long and winding — his first leap came when his family left home to live and work in Gisborne; the town in Poverty Bay on the northeastern side of New Zealand.

Great Barrier Island, which was named by Captain Cook, is a 4½-hour ferry ride out from Auckland

There Gibson-Park joined Gisborne Boys High School and started playing rugby around the same time as Blade Thomson, who ended up with ten Scotland caps. Their coach was a man called Tom Cairns, now the headmaster, who knew Mark Robinson, then the Taranaki Rugby chief executive, now the departing head of New Zealand Rugby. Robinson gave Michael Collins, a former Chiefs, New Zealand A, London Irish and Glasgow Warriors prop a job as a rugby development manager, and he went about finding good kids. Gisborne Boys’ High was a decent place to start.

One recruit was Gibson-Park, who he convinced to make the eight-hour drive over from Gisborne to New Plymouth, on the opposite side of the country, to join Tukapa Rugby club and the Taranaki Bulls provincial side.

“A lot of our players would leave school and go to university, so we needed to find kids that didn’t want to go to university but wanted to do trades,” Collins says.

“When he grew up he worked on fishing boats, and started building an apprenticeship and working in construction. The first year he came in out of school he was a skinny kid, really quiet but he had this confidence about him.

Gibson-Park said that he spent much of his childhood immersed in nature on the island

“He was slight, but really tough. We had no concerns around putting him into senior club footy, even though he would have been 75kg ringing wet.

“As an 18-year-old he was so tough and could take a hit, having grown up playing with older kids. He was one of the few guys who we never had any dramas with. He had really strong support from mum and dad, who weren’t helicopter parents. They’re the exact opposite. They would float in, watch a rugby game, say g’day to us, and his dad was the most laid-back character in the entire world.

“When you spoke to Jamo, he wouldn’t say much in a crowd but if you asked him a question he’d be quietly spoken and would nail the answer nine times out of ten. He wouldn’t stand out as a rugby nerd, just an immensely talented kid who never showed off or made too much of it.”

Gibson-Park quickly started to fly in Taranaki. He paired with Beauden Barrett at half-back, behind lock Scott Barrett and turned heads whether playing sevens or XVs. His fitness trainer was a Welshman, Aled Walters, who is now coaching him with the Lions. It is funny how the world works.

“He scored some fantastic tries [in] that first year, you could see what a special player he was,” Collins remembers. “He ran great support lines, he was really quick, he was always really fit, had a great instinct for running support lines, and his box-kick always set him apart. He just had this long box-kick, before box-kicking was a thing.”

Aged 21, Gibson-Park quickly moved up to the Blues Super Rugby side in Auckland for three years around the time when he played eight times for the Maori All Blacks.

Gibson-Park played eight times for the Maori All Blacks

CLAUS ANDERSEN/GETTY IMAGES

Yet despite having so much so soon, he could not find a way into starting teams, or the All Blacks, stuck behind TJ Perenara — who ended up winning 89 caps for New Zealand and a World Cup — and Jono Kitto — who did not make it, so moved to Europe. The Taranaki crew always felt that guys from Canterbury, like Kitto, were overly favoured.

“It was more his game management,” Collins says of Gibson-Park. “He was a really good runner, a really good passer. He had a box kick like no one else, but it was controlling the game, controlling his forwards, because he wasn’t the loudest guy. He missed out on the New Zealand under 20s, but I always believed he was good enough. Everyone in Taranaki knew he was good enough — he was just a bit slight. Back in Gisborne and Great Barrier, there probably wasn’t a lot of weights programming.”

When Gibson-Park was at the Hurricanes, in 2016, where he sat behind Perenara, Collins fielded a phone call. It was from Leo Cullen, the Leinster coach. He wondered if the 24-year-old scrum half was available.

Gibson-Park joined Leinster from the Hurricanes in 2016 aged 24

DAVID RODGERS/GETTY

“They wanted to negotiate an early release,” Collins says. “He still had a year on his Taranaki contract, but we had a chat and we understood that we were a pathway for players and we would never stand in his way. We were happy for him.

“We would’ve loved him to stay in the New Zealand system, but were also happy that he was going off to play professional rugby for Leinster.”

By 2020, he was an Ireland international, having completed three years of residency under World Rugby regulations, and supplanted the seemingly-immovable Conor Murray as Ireland’s first-choice No9. In 2023 he became an Irish citizen, and now he conducts the Lions’ tempo in Test matches alongside Finn Russell.

Collins does not lament Gibson-Park’s departure. Maybe, he thinks, a race-to-the-bottom for talent means that kids are pushed through too early, then sit on benches, and are squeezed out. Equally, professional contracts are sparse in New Zealand, with about 190 deals across the five Super Rugby franchises. Some are bound to slip away — and that is why he does not agree with the criticism of Gibson-Park being a “foreign Lion” and undeserving of his red jersey.

“Two of our All Blacks who came through the academy at the same time as Jamo were Waisake Naholo and Seta Tamanivalu. They’re Fijian boys,” Collins says.

Gibson-Park helped the Lions defeat Australia in the first Test on Saturday

BRENDAN MORAN/SPORTSFILE

“Waisake came from his village to live with his uncle in Wanganui, did a year’s schooling and we picked him up into the Taranaki academy about the same time Jamo came. Seta came from an outer island of Fiji, went to secondary school in St Kentigern’s in Auckland, and then we picked him up for the Taranaki academy. They both went on to play for the All Blacks. It’s no different from what Jamo’s done. It seems to be more widely accepted down here in the South Pacific.

“If I put myself in those players’ shoes, it’s an opportunity to travel, to experience a different culture and a different lifestyle. As New Zealanders, we all want to leave New Zealand for a couple of years, and some go back. Rugby’s a great vehicle to take you around the world and to give you unique experiences.

“Jamo’s been performing at a high level for Ireland for three or four years, and they have been close to the number one team in the world — which obviously grates us New Zealanders — but we’re just so excited and proud of him for having those experiences.

“I don’t feel it’s a shame he didn’t play for the All Blacks, I’m just proud that he’s playing for Ireland and playing for the Lions.”