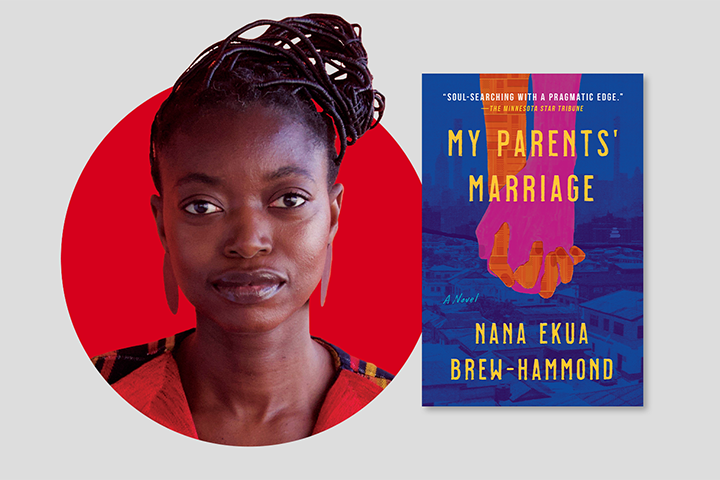

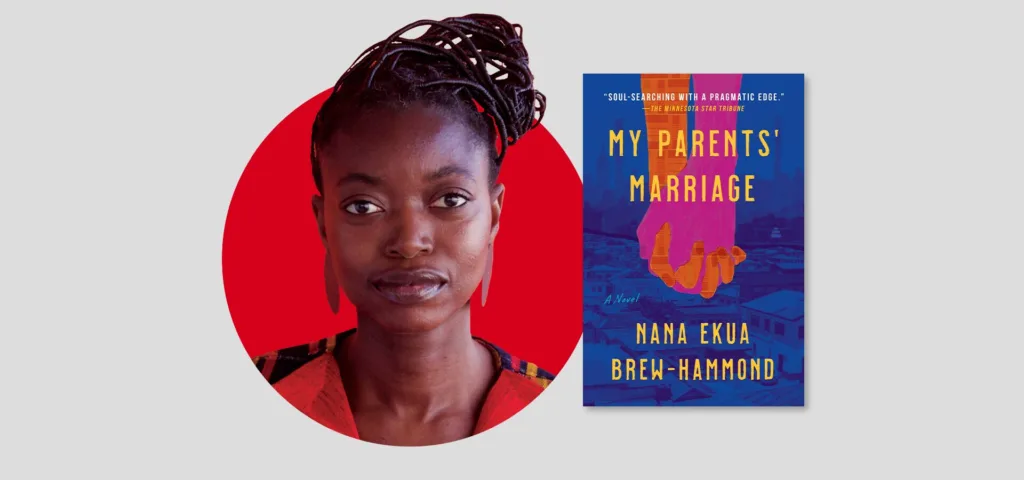

Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond has previously written both a children’s and a young adult book, but her latest release, My Parents’ Marriage (Amistad, 2025), tackles new themes for a new audience. Set in Ghana and New York City in the 1970s, the adult novel follows Kokui, a young woman who grows disillusioned with her parents’ lives and seeks out a different kind of romance for herself.

In conversation with PEN America’s communications intern Julia Goldberg for this week’s PEN Ten, Hammond reflects on the challenges of writing fiction for an older audience, Kokui’s strong bond with her sister, and the enduring nature of storytelling itself, which she says continues to give her hope amid escalating attacks on free expression. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble).

You’ve previously written a young adult novel (Powder Necklace) and, more recently, a children’s book (BLUE: A History of the Color as Deep as the Sea and as Wide as the Sky). How did you know that My Parents’ Marriage should be an adult novel? What was most surprising or difficult about writing fiction for an older audience?

I wrote My Parents’ Marriage for adult and mature readers because, at its core, this novel is an invitation to consider how your parents’ union might have impacted how you show up in relationships. I think you need some experience and maturity to be able to reflect on that with some level of humility, compassion, and grace. My Parents’ Marriage is also about the nuanced weave of culture and class, tradition and modernity, religion and colonialism, patriarchy and womanhood—with the characters making some complicated decisions at the intersections of each. Again, I think you need some life experience under your belt to appreciate the paths some of the characters choose, even if you don’t agree with their choices.

As for my experience of writing fiction for an older audience, I’d say one of the hardest parts of writing My Parents’ Marriage was finding the sweet spot in articulating the inner transition of early adulthood—when the self-righteous certainties you carry from youth confront life’s many gray areas and you are now the adult who must decide how to respond to them. That’s the journey my main character Kokui makes in this novel.

Early in the novel, Kokui describes herself as stuck in a “dizzying circle of irony.” Her family’s wealth affords her the privilege of rejecting any man’s sexual advance with ease, but it also enables her father to pursue as many wives as he’d like, much to Kokui’s dismay. What drew you to explore the relationship between class and gender/sex in My Parents’ Marriage?

I think privilege is such an interesting topic. With all of the comforts it affords and doors it can open, in many ways privilege can also be a prison. A prison of ignorance to the struggles of others. A penitentiary of unwieldy mores to maintain your position. A solitary confinement of fear and pretense that prevents people from getting close. I wanted to explore this irony in My Parents’ Marriage and how acutely this tension plays out in Ghana where class divisions are so stark and the privileges that come with being male are pretty blatant.

Many of the relationships in the novel, whether between parent and child or husband and wife, are quite complex. Kokui and her sister, Nami, stand out as one true exception. Why did you choose to foreground such an uncomplicated, tender sibling relationship in the novel?

Thank you so much for seeing that in Kokui and Nami’s bond. I think of their relationship as complicated in its own way. Nami is overshadowed by Kokui’s dramatic personality and overlooked in some ways because of it, while Kokui admires her sister’s thoughtful, measured approach to life and wishes at least some of that came more naturally to her. But I guess, thinking more closely about your question, I chose to write their relationship in the way I did because I wanted to show their overarching instinct to protect one another as a counterpoint to the desperately competitive, adversarial dynamic between many of the other women in the book. With each other, the sisters’ weaknesses are not vulnerabilities to exploit. Rather, when situations arise that require Kokui to be out front, Nami can exhale and trust her sister to push the door open for both of them. And when Kokui needs Nami’s level head to sort through the details of whatever they’re facing, she can be sure she has a true advocate looking out for both of their best interests.

I think privilege is such an interesting topic. With all of the comforts it affords and doors it can open, in many ways privilege can also be a prison. A prison of ignorance to the struggles of others. A penitentiary of unwieldy mores to maintain your position. A solitary confinement of fear and pretense that prevents people from getting close.

Kokui repeatedly emphasizes that she craves nothing more than a husband who will stay loyal to her, sparing her the pain and humiliation that her mother suffered at the hands of her father. Did you develop the novel around this theme, or did you realize only later in the writing process that it would be central to your work?

After many years of rewriting and revising an earlier narrative set in Ghana that spanned almost four decades, I arrived at this tighter time period and theme. The idea came to me as I found myself in a deepening relationship. I wanted marriage, but I had great anxiety connected to my own past relationships and many of the unions I had seen growing up. As I came to this realization, I started hearing the same in conversation after conversation with friends. I began to write into this realization with trepidation not sure I was willing to explore this in novel form, but I felt more and more emboldened as it became clearer that I had tripped over a well that was deeper than me and my friend group.

In the copyediting phase of My Parents’ Marriage, I got another unexpected confirmation. Watching season six of the reality dating show Love Is Blind, I was riveted by the relationship between Amber Desiree “AD” Smith and Clay Gravesande because he repeatedly expressed fear of marriage due to the anguish he witnessed in his parents’ union. After Clay declined to say “I do” to AD at the altar, I was so touched by the candid talk his mother had with Clay’s dad about their son’s struggle and the discussion it sparked. Talk show host Tamron Hall said it best: “There’s a bigger conversation about this trauma and pain, and how it blocks love.”

The novel is set in both Ghana and New York City in the 1970s. What drew you to these settings and this time period?

I set the book in the 1970s because it was an acutely rich moment in Ghanaian history and in women’s history around the globe. It was the decade Nigerian singer and activist Fela Kuti released his hit “Lady,” in which he crooned about African women: “she go say him equal to man.” It was the era when The Pill and abortion were being hotly contested in U.S. senate hearings. And in Ghana, it was a period where powerful men invited women to trade their sexuality for financial spoils.

My Parents’ Marriage opens in December 1972, eleven months into the military regime of Colonel Ignatius Kutu Acheampong. The Acheampong administration was noted for its men lavishing their girlfriends with extravagant gifts, including houses and cars, at the expense of the nation’s purse. The practice even went on to inspire the crude colloquialism “fa wo to, bɛ gye Golf” (“bring your ass and get a [Volkswagen] Golf.”). For many ambitious young women living during this government, financial ascendancy meant being attached to the right man.

In general, Ghanaian culture is patriarchal so Acheampong’s administration was not necessarily introducing anything new, however, the leadership’s dalliances enshrined a Sugar Daddy subculture that my novel’s protagonist Kokui had to confront in her desire to make independent choices about her future.

In your previous PEN Ten interview, you mentioned that your Ghanaian identity was called into question when you lived in Ghana and that, as a result, you’re hypersensitive to how those in Ghana receive your work. Did you have a specific readership in mind while writing this novel? To what extent did you consider how certain aspects of the novel, such as Kokui’s disillusionment with her parents’ lives, might be received by that readership?

I wrote this novel thinking about the generations who lived through the transition from “The Gold Coast” to Ghana, and their children. Prior to sitting with the ideas in this book and writing My Parents’ Marriage, I had only thought of the switch from colonialism to Independence in political terms. With this novel, I really wanted to meditate on the personal. What did it feel like to be born and raised in a society that was, in real time, experiencing the push and pull of generations’ old traditions and their hybridization, dilution, or demonization under colonialism and then Independence—all while the political and economic situation began to grow more and more volatile? I wanted to examine what that felt like for them, even as they had to figure out all of the other issues of life like work, romance, and family. And I wanted to explore the impact their choices had on the generation that came after them—not as an indictment but a bridge to mutual understanding of each other and where the culture stands now. I hope My Parents’ Marriage opens up an opportunity for readers across Ghana’s older and younger generations to sit together and discuss these things with candor and without judgment.

With this novel, I really wanted to meditate on the personal. What did it feel like to be born and raised in a society that was, in real time, experiencing the push and pull of generations’ old traditions and their hybridization, dilution, or demonization under colonialism and then Independence—all while the political and economic situation began to grow more and more volatile?

In that interview, you also identified Buchi Emecheta, Tayari Jones, Zadie Smith, Janet Fitch, Sharon Draper, and Chinua Achebe as your “literary north stars.” Which of these authors and their works most inspired the content and style of My Parents’ Marriage?

Buchi Emecheta’s The Joys of Motherhood is the first book I read that examined the passage from young womanhood to wifehood to motherhood with such detail and care—and the first time I remember really considering who my parents were before they had us children. Tayari Jones’ Silver Sparrow and An American Marriage are both a master class in conveying the myriad ways the tensions endemic in a wider culture can seep into personal relationships and families. Janet Fitch’s White Oleander so beautifully navigates the subtleties that distinguish the mother-daughter relationship. I love that Zadie Smith canonizes characters and communities who are usually ignored in “great literature,” and does so with fresh wit and humor. I also admire how Sharon Draper’s writing in Copper Sun presents history in a way we don’t often hear, and that it feels so current and urgent. Chinua Achebe’s Man of the People is a powerful study of the human susceptibility to compromising core values. These works didn’t directly inspire the content of My Parents’ Marriage, but reading these authors’ nuanced explorations of marriage, family, and the systems that make up culture inspired me to explore the same in my own way.

Every month, you co-lead the Redeemed Writers Group, which is open to writers of all genres, including journalists, songwriters, graphic novelists, and comedians. How do you facilitate sessions for such a wide array of participants? What do you hope writers of such varying styles can learn from one another?

We structure sessions with the goal of supporting writers on their faith journey and on their writing journey. In a usual meeting, we spend the first half discussing a passage of scripture and considering the ways it informs our everyday experiences as writers managing the demands of finding time and space to write, figuring out how to navigate social media, handling rejection, and handling success, for example. We talk, too, about what it means to us to be a writer and a Christian in the world: What does loving God and loving our neighbors as ourselves practically look like as writers?

Then, we move into a time of sharing our works in progress for open critique. It’s wonderful listening to writing from such a mixed group, and sharing and receiving feedback. I feel like the speculative fiction writers in the group have made me more cognizant of the world I’m building in my stories, and more confident about conveying the things that make it unique.

Also, we are all over the map in terms of career stages, and have expertise in a range of disciplines from podcasting to marketing to illustration, so we share skills and advice and encourage collaboration.

PEN America’s most recent banned books report found that during the 2023-2024 school year, 36% of all banned titles featured characters of color. In May, PEN America also identified over 350 words — including “immigrant,” “minority,” and “women” — that have been banned or flagged on government websites and documents. Amid growing attacks on free expression, what continues to bring you hope as an author?

I’m encouraged by all of the good people who work exceedingly hard with meager resources to deliver stories to readers with the goal of helping them articulate their own lives or inviting them to learn about others. But what gives me the most hope is the enduring nature of storytelling itself. Telling stories is as old as humanity. It’s part of who we are, how we connect with one another, and how we understand our existence—that’s why stories survive migration, and get passed down for generations. We will always tell stories, and we will always share the stories that mean something to us. That gives me comfort and helps me stay focused.

I hope My Parents’ Marriage opens up an opportunity for readers across Ghana’s older and younger generations to sit together and discuss these things with candor and without judgment.

You’ve now published fiction, poetry, and edited an anthology of your own. What’s next for you?

I am at the very beginning stages of a new novel for adult readers, and I have two children’s picture books coming to follow. Blue—Yellow releases in summer 2026 and Red in fall 2027.

Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond is the author of the children’s picture book Blue: A History of the Color as Deep as the Sea and as Wide as the Sky, illustrated by Caldecott Honor Artist Daniel Minter; and the young adult novel Powder Necklace. Her short fiction for adults has been included in the anthologies Accra Noir, Africa39, New Daughters of Africa, Everyday People, and Woman’s Work. Learn more at nanabrewhammond.com.