Angela Webb-Milinkovich would be the first to admit that her look is not regal: the care worker from Minnesota has tattoos, a mullet and a nose piercing, but she may play an extraordinary part in royal history.

This Midwesterner has a story that suggests she may be a secret descendant of Queen Victoria and her devoted manservant John Brown.

It sounds sensational, but Fern Riddell, a respected historian, believes it may be true. She has delved deep into the relationship between Victoria and Brown, uncovering reams of material indicating that the two were more than friends.

Riddell’s book Victoria’s Secret and Channel 4 documentary Queen Victoria: Secret Marriage, Secret Child? will prompt debate about the nature of the couple’s love, but Webb-Milinkovich may be the coup de grace.

Webb-Milinkovich with the historian Fern Riddell

ROBERT PERRY FOR THE TIMES

Her family’s story is that they are descended from Victoria and Brown’s secret child, and Webb-Milinkovich is willing to test its veracity. “I feel pretty confident that there’s some legitimacy to it. It’s not something that I myself would ever be able to confirm. It was just a fun thing for my family to share,” she said. “I think I would definitely rock a tiara.”

Riddell says her search has unearthed so much evidence that she feels it is hard to deny that the pair had a romance. To evaluate that claim, we ought to start at the beginning.

Victoria admitted, years after meeting Brown, that she had been “irresistibly drawn to him”. The young and handsome servant was among the staff at Balmoral when Victoria and her husband, Prince Albert, first arrived in 1848.

Victoria and Prince Albert in 1854

ROGER FENTON/GETTY IMAGES

He worked closely with the royal couple and was a familiar presence when Victoria suddenly found herself a widow in 1861. She entered a long period of seclusion, during which she came to depend on Brown and he became her favourite.

Brown and Victoria at Balmoral, circa 1868

W&D DOWNEY/GETTY IMAGES

She commissioned medals for him, increased his salary, insisted that he be close by and included him in portraits:

An oil painting of the pair, said to have been a gift from Victoria to Brown to mark his 50th birthday in 1876

CHARLES BURTON BARBER

His death was even noted in the Court Circular, printed in The Times. It was described as a “melancholy event” that caused “the deepest regret” to the Queen; Brown was said to have had “the real friendship” of Victoria and that “to Her Majesty the loss is irreparable”.

Victoria dismissed rumours about them as “ill-natured gossip in the higher classes”, but the evidence Riddell has amassed suggests otherwise.

Chief among the discoveries is a piece of physical evidence. The John Brown Family Archive has a photograph of a cast of his hand, made on Victoria’s orders in the days after he died in 1883.

She had done exactly the same with Albert. The cast of Albert’s hand would be buried with her, but so would a picture of Brown, a lock of his hair and his mother’s ring, which Victoria had worn.

Alongside this are reams of documentary evidence through which Riddell has trawled to make her case. This includes a never-before-seen family history of Brown which Victoria had commissioned — an odd thing to do for someone who was just a servant. However, perhaps the most telling is a rare journal entry in the Brown family archive.

Victoria’s diaries were edited heavily on her instruction after she died. Her daughter Beatrice did the bowdlerisation and destroyed originals. However, Victoria had made a copy from her own diary after Brown died and gave it to his brother Hugh. It tells of how she and her “beloved John” confessed their love for each other:

Victoria is often tender, using terms such as “beloved John” and “darling one”. A short poem refers to Brown as “my heart’s best treasure” and implores that his answer “loving be, and give me pleasure”.

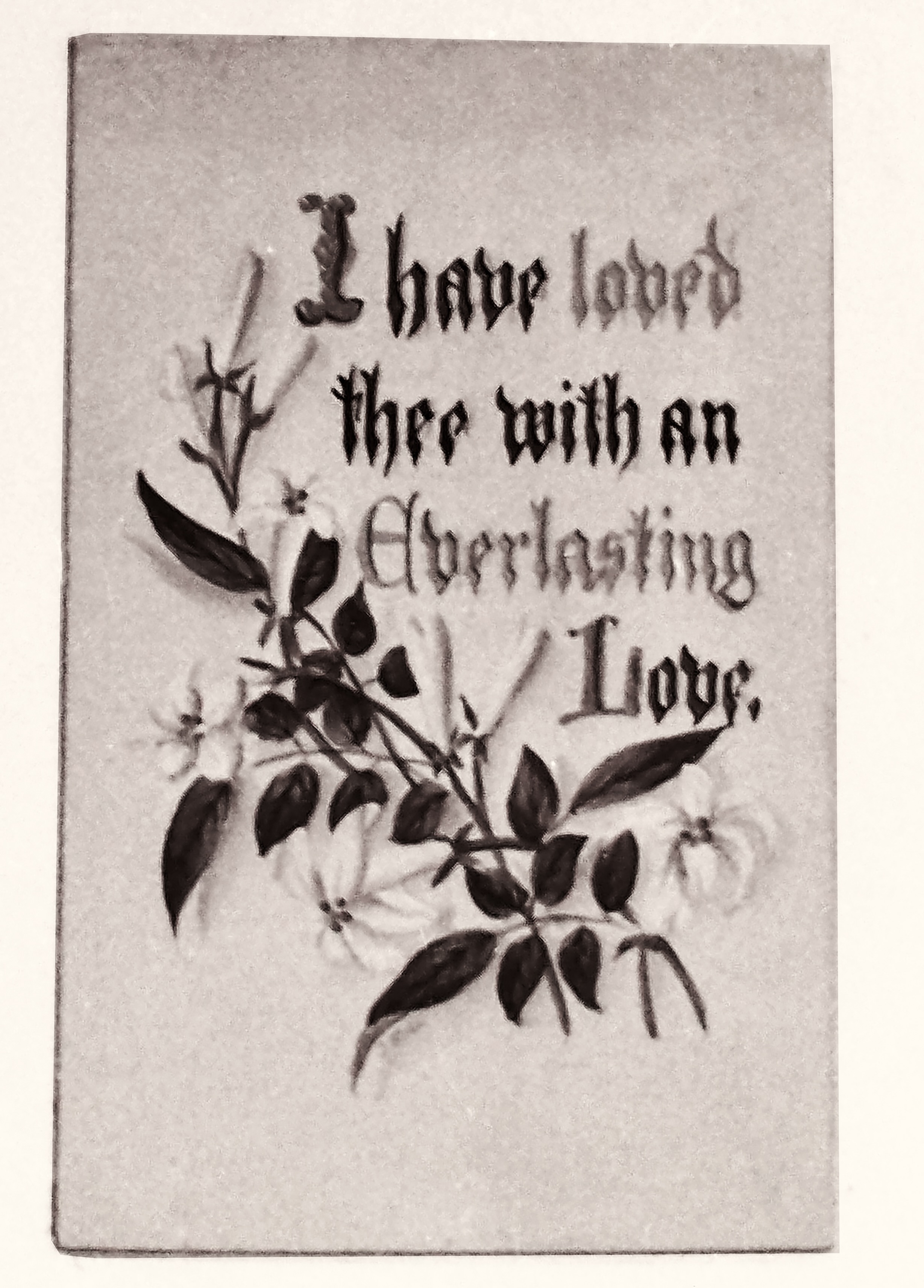

A notecard from Victoria to Brown also expresses her love for him:

Riddell notes that in a letter after Brown’s death, discovered by the art historian Bendor Grosvenor in 2004, Victoria paralleled the loss of Albert. She wrote, referring to herself in the third person: “The Queen feels that life for the second time is become most trying and sad to bear deprived of all she so needs.”

Critics will be quick to point out that Victoria often referred to herself and to Brown as a “friend”. Many will argue that this was meant literally and that Victoria knew to stay on the dutiful side of the line. Riddell argues that the word “shouldn’t blind us to the depths of feelings” between the pair, which Victoria’s language makes plain.

“Friend is always preceded by ‘beloved’ or ‘devoted’, ‘truest’ and ‘best’, terms many wives called their husbands,” Riddell said. “While romantic language often existed between friends of the same sex, we have to remember this is between a widow and an unmarried man, a queen and a servant.”

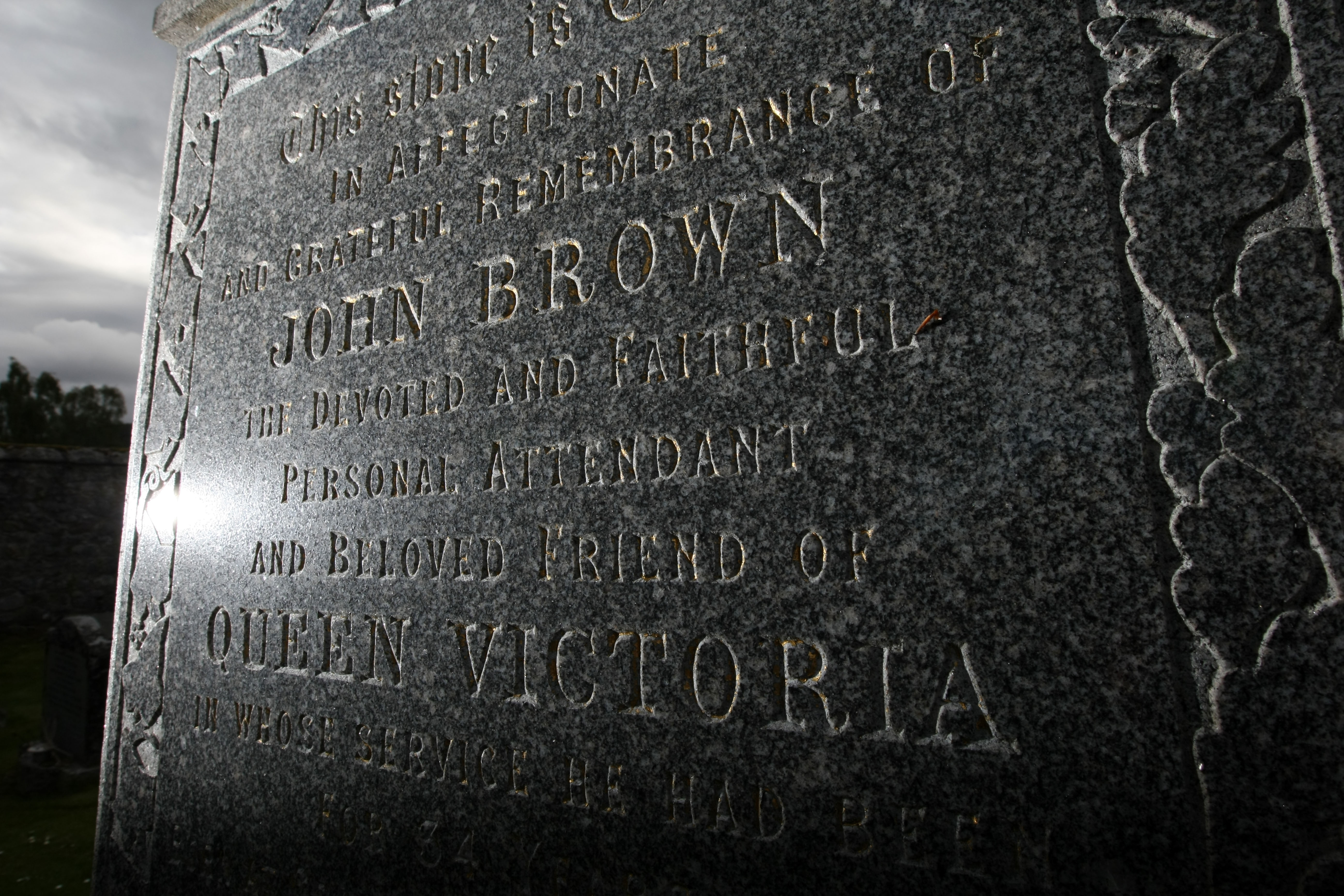

John Brown’s gravestone, which describes him as “beloved friend of Queen Victoria”, at Crathie Kirkyard near Balmoral

ALAMY

Riddell also argues that historians have too easily assumed that Victoria was a woman of unparalleled reserve. “We’ve eradicated who Victoria was as a woman in favour of seeing her just as queen,” she said. “It really, really matters to me that we give her back her womanhood.”

She thinks there is a case to be made that the pair had an “irregular marriage”, which was common in Scotland at the time. A deathbed confession by one of the Queen’s chaplains, the Rev Norman Macleod, supposedly expressed his regret at overseeing the ceremony. This confession was recorded indirectly and some years after the fact, but Riddell thinks it has been too quickly dismissed.

In the 1950s the historian Harold Nicolson said that he had found “marriage lines”, a form of marriage record, for Victoria and Brown in a book at Balmoral.

Balmoral Castle in the late 19th century

THE PRINT COLLECTOR/GETTY IMAGES

Riddell points to Victoria’s insistence on how Brown should be treated. Her children were expected to shake his hand as if he were an aristocratic equal — when her son Alfred refused to do so, he was expelled from Buckingham Palace — and Brown’s bedroom was next to Victoria’s. The historian also suggests that a signet ring Brown wore from 1872 may have been a subtle sign of a morganatic marriage, one between people of mismatching social ranks.

“In conversations that we’ve had for the documentary, that they were married seems to be the general feeling among some parts of the Balmoral community even today,” Riddell said.

“Their relationship has been downplayed and sanitised,” she added. “I hope we give John Brown back his place in history and his legacy, which is that he was Victoria’s de facto royal consort for 20 years.”

The marriage argument will fire up debate, but it’s a storm in a teacup compared to the suggestion that the couple had a secret child. This was not something Riddell was looking for when she contacted Brown’s surviving relatives in Minnesota.

On paper, she and her sister Annette are the great-great-grandaughters of John Brown’s brother Hugh.

As well as a small basket of fascinating heirlooms, including a brooch commissioned by Victoria, Webb-Milinkovich told Riddell that her family had a story they “told at dinner parties”.

The brooch, commissioned by Queen Victoria for Hugh Brown’s widow, containing a lock of his hair, is among a collection of heirlooms owned by Webb-Milinkovich and her sister

IMPOSSIBLE FACTUAL

She said: “The story that my family grew up with is that John Brown and Queen Victoria had a romantic relationship. They went on a long boat journey. After that a child was produced and from that child came my family’s lineage.”

Both Webb-Milinkovich and Riddell have said they do not know if this is true, but Riddell thinks it is a possibility worth exploring.

She looked into the idea that the story might have become muddled. Victoria and Brown never took a long boat journey, but Hugh and his wife, Jessie, emigrated to New Zealand in about 1865. Their daughter Mary Ann was registered there, but their family home is not marked as the place of birth.

Then, in 1874, Victoria paid for Hugh’s family to travel back, housing them at Balmoral. When Victoria moved to Windsor, they followed.

For Webb-Milinkovich’s story to be true, Mary Ann would have to be the love child. It would be incredible and many would call it improbable, but it is not impossible.

Victoria’s daughter Vicky noted that “Mama so longed for another child” after Albert’s death. She was in her forties and, while some thought it meant she could no longer have children, a prolapsed uterus found after her death is in mothers later in life. The Queen’s seclusion would have given some privacy to disguise a pregnancy. Illegitimate royal children by men were frequent and dealt with in a number of ways. Riddell wonders if a woman’s illegitimate children would be so different.

A DNA test could prove Webb-Milinkovich’s family story. Ideally, several descendants of Victoria — many are available — would be needed to give the best chance of identifying a match. Webb-Milinkovich is happy to do a test and accept the result. It may end up being a footnote in this story, or it could be a moment in royal history.

ROBERT PERRY FOR THE TIMES

“My family’s story is something that I’m proud of,” she said. “I would love for this story to get out. Especially if it’s a legitimate story.”

Queen Victoria: Secret Marriage, Secret Child? will be broadcast by Channel 4 at 9pm on July 31