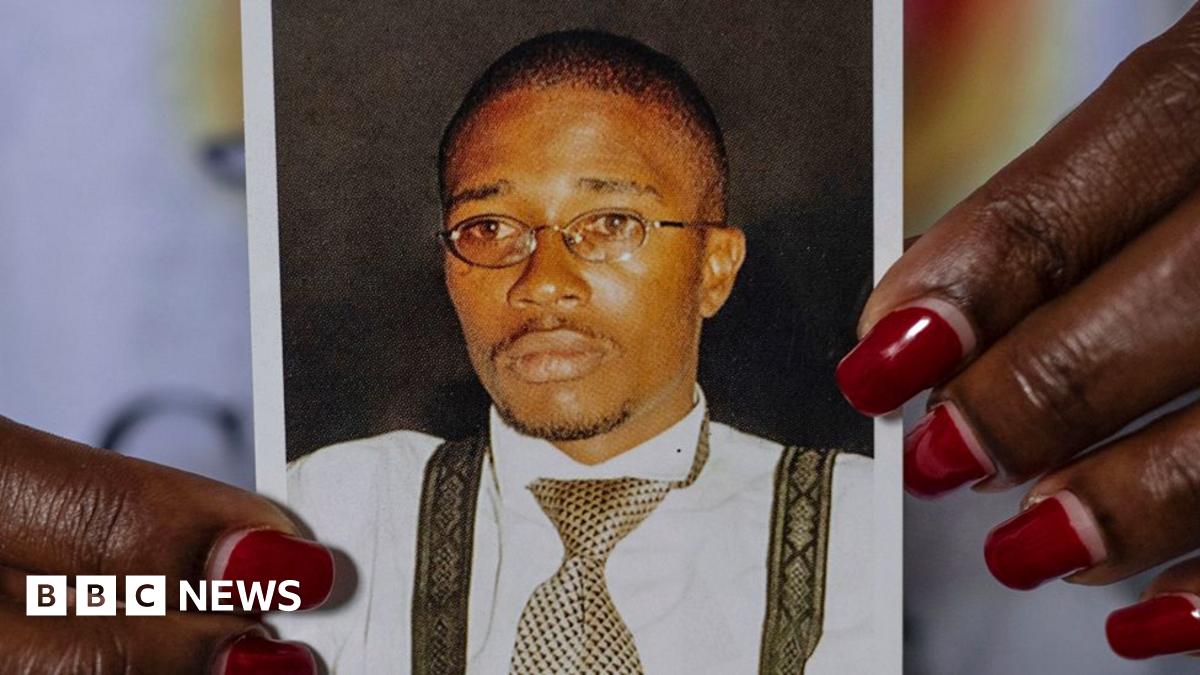

Kositi took up his mission – and in particular his efforts focused on helping street children, Fr Tedeschi said.

The region around Goma has known decades of conflict and is currently at the centre of a rebellion that has seen a powerful rebel group take over the city and swathes of territory surrounding it.

Kositi, “very affected” by the fate of children caught up in successive traumas, set up one of Sant’Egidio’s “Schools of Peace”, external – which offer food and other assistance to get children an education.

Today Goma’s School of Peace is named in honour of him and has become an actual school.

But in the early 2000s, the young undergraduate was often helping street children financially with school fees or food – or assisting them to become self-reliant in a city where almost everyone was struggling.

“What struck me,” said Fr Tedeschi, “was how Floribert was someone who took the life of others very seriously and more importantly, he would ask himself a lot of questions to understand what the roots of poverty were – the misfortunes of people.

“He liked talking, to confront these problems.”

Kositi’s reach went beyond DR Congo’s borders. In Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, some 100km (60 miles) east of Goma, Bernard Musana Segatagara, a Sant’Egidio fellow, also remembers him.

“Changing Africa and building peace was our shared dream as we observed a growing network of friendship. I think living in a region of tension was making our friendship even more special,” he told the BBC.

After graduating in 2006, Kositi began training as a customs official in the capital, Kinshasa, before taking up a senior post on the border between Rwanda and DR Congo in April 2007.

The rice dispute involved a consignment of around four or five tonnes – which he had tested as he was worried about its safety and then ordered that it be destroyed.

“At first that pushed the smugglers to try and bribe him, and later to threaten him. And Floribert always refused,” Fr Tedeschi said.

“He refused based on his Christian principles. At one point he asked a doctor – a nun working in Goma, who was a friend – so he could really understand the dangers this rice would have represented to the civilian population.

“And that’s what led him to think: ‘So me as a Christian, I can neither accept money nor that these people risk dying because of this poisoned food just because of corruption.'”