U.S. President Donald J. Trump has torn up the WTO’s rule book and unilaterally raised tariffs on almost everyone, including the EU.

The EU even agreed not to retaliate against a 15 percent across the board tariff hike in its deal with Trump, to the dismay of some.

More on:

But for now, the U.S. keeps on importing, limiting the damage to the rest of the world economy.*

Follow the Money

Brad Setser tracks cross-border flows, with a bit of macroeconomics thrown in.

Imports are running ahead of their 2024 pace, even excluding pharmaceuticals.

China, on the other hand, is squeezing foreign imports out of its market.

It hasn’t quite mastered top-of-the-line chips, protecting Taiwan.

But it has mastered autos—both EVs and ICEs.

More on:

And construction equipment. And industrial robots. And most specialty chemicals. And batteries, permanent magnets, solar PVs and their chemical precursors, industrial diamonds, wind turbines, and high-speed rail.

While China hasn’t quite mastered the production of top-line civil aircraft, Comac is ramping up the production of the C919. Plus, there are signs that the Chinese content of the made-in-China Airbus narrow bodies is rising.*

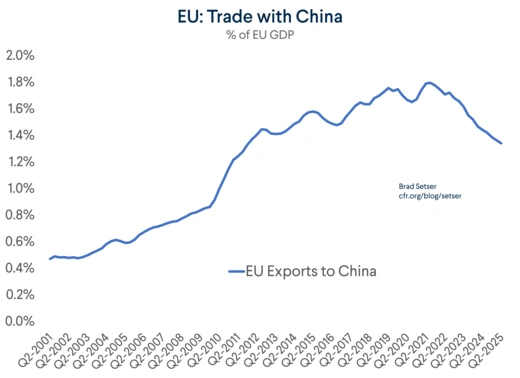

In other words, China’s continued manufacturing boom is eating into core European export strengths. Exports have been in steep fall as as a share of Europe’s economy since 2022.

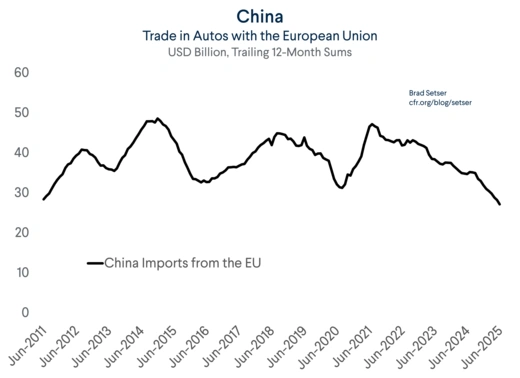

That is obvious in autos.

Extend that series into a forecast, and European exports of autos will be down to around $10 billion by 2027.

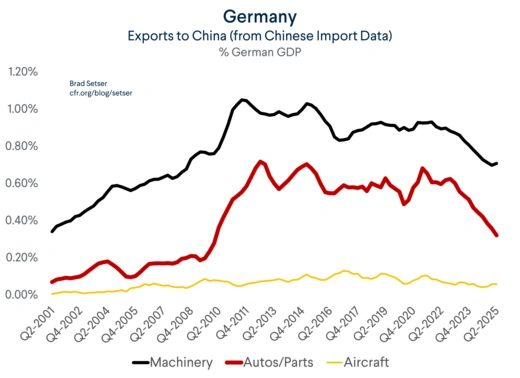

No wonder Germany has been hit especially hard; it is now more widely recognized that falling exports to China are an important reason why Germany’s overall economy has stagnated over the last 5 years.

But the export slump is visible in most industrial sectors.

And it is a big enough shock to be of macroeconomic significance.

European exports to China (measured by China’s imports) are now down about half a percentage point of European GDP over the last few years.

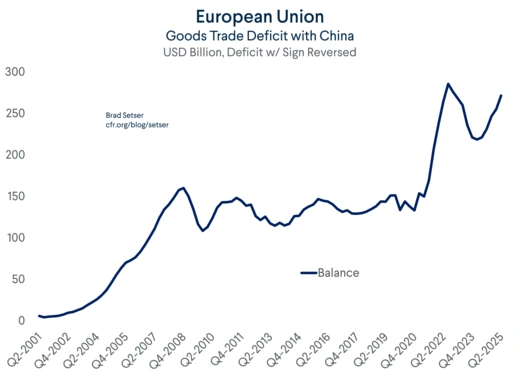

While European imports from China rising again, the EU’s trade deficit with China is set to double between 2020 and 2025 in euro terms: that is a negative shock to a European economy that hasn’t exactly boomed over the last five years.

These calculations ignore the additional impact of increased Chinese competition in third party markets.

The second China shock—which for Germany is really the first China shock—now shows up basically everywhere. The auto shock, for example, is not over.

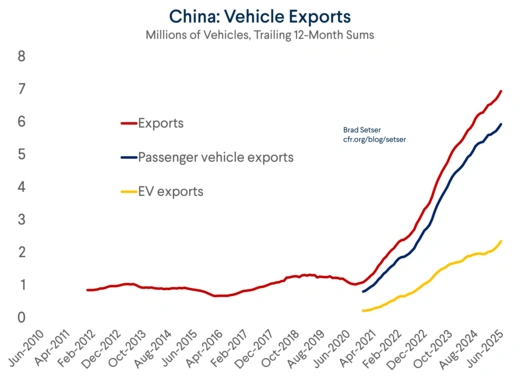

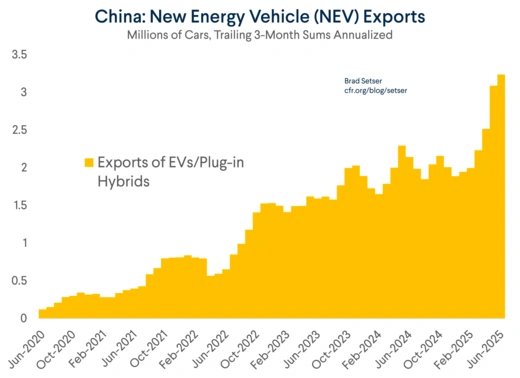

EV exports (in volume terms) have overtaken ICE exports in leading China’s export surge, which continues to rise in volume terms (pinging Adam Tooze here…) EV exports in Q2 were running at a pace of 3 million cars on a rolling 3-month basis, which is significant relative to the current global demand for EVs once China’s own (large) domestic EV market is netted out of the data.

Of course, these EVs show up in the continued Chinese dominance in global exports, as Chinese exports continue to outperform global trade.

It also shows up in the large contribution to growth that exports have provided to China in recent quarters. That growth was around two percent; that’s a bump Europe would have loved for itself. China saw this level over last four quarters from net exports alone.

Von der Leyen told China’s leaders that the European trading relationship is at an inflection point. She needs to be back that point up with additional action if China doesn’t change.

Counter-industrial policies for example. If China isn’t going to change, countries have to find ways to either wall off their domestic market or subsidize production of key inputs.

Europe’s wind industry shouldn’t be allowed to follow the path of Germany’s solar industry, and permanent magnets are too important to both autos and rearmament (fighter jets and missiles for example) for their production to be remain concentrated in China.

Broader tariffs on Chinese auto exports. China isn’t just exporting battery electric cars, and the 17% tariff that emerged from the countervailing duties investigation on BYD is rather low (the yuan’s depreciation against the euro has more or less offset the tariff on BYD, and Tesla for that matter).

A new approach to pressuring China to allow its currency to rise also would be welcome. China appears to be intervening through the state banks to keep spot below the fix, which is new, and addressing the underlying macroeconomic imbalances that have led to a weak currency and reliance on exports for growth.

I would hope that Macron, Meloni, and Mertz would all back such a policy shift.

There are lessons here for Trump’s team too, if they are serious about a U.S. manufacturing revival and not just letting Trump enjoy his oval office tariff joyride.

Trump’s advisors will note, correctly, that China has long had significant tariffs.***

But China’s success also stemmed from industrial policy (which remains a bad word in certain Republican circles, though I note that the functioning part of the Department of Defense seems to be doing it) and a Chinese private (or civil-state fusion) sector that was willing to accept low returns on equity and get out and build (often too much).

More recently, success in China has stemmed from a willingness to let the Chinese yuan slide—first against the dollar, and then against the euro. No worries about losing “yuan dominance.”

Neither new commodity purchase promises (phase one, resurrected, without the structural reforms…) nor a new channel for recycling China dollar’s surplus into real U.S. assets (a Chinese-financed, American sovereign wealth fund is an oxymoron).

Set that aside though.

Europe is clearly getting hit hard by China’s industrial policy successes—and now by a weak yuan. Its response has been inadequate.

Time for Europe to step up with a counter industrial policy of its own and start to take the issues around China’s macroeconomic imbalances seriously.

* That could change; U.S. firms won’t keep eating the tariffs cost for much longer; I like Goldman’s model

** See German customs data; exports of civil aircraft to China have trended down, and Airbus Germany makes the 320/321.

*** China’s auto sector developed behind a 25 percent tariff wall back when Europe’s tariff was 10, the U.S. tariff was 2.5, and Japan’s tariff was zero. China only reduced the tariff to 15 when it knew that there was more than enough Chinese capacity to meet China’s internal demand.