Two weeks ago while walking through town on the way to the supermarket, I came across a deeply distressing scene. On a stretch of pavement near Castle Square tram stop was a man flat on his back, not moving.

He looked like he’d been sleeping rough, and he had a needle in one hand. Around him were half a dozen bystanders in intense distress, waiting for an ambulance while desperately searching for a pulse.

I found out later from the Yorkshire Ambulance Service that the man regained consciousness in the ambulance, and refused to be taken to hospital. But increasing numbers of people in Sheffield don’t make it through.

The most recent figures from the Office for National Statistics show that drug deaths are steadily rising in Sheffield. 60 fatalities were recorded in 2023 – 13 more than in 2022 and 17 more than a decade ago (while figures for 2024 have not been released yet, The Tribune report that, anecdotally, this year has “almost certainly been worse than most”).

Many of these deaths involve extremely vulnerable people with complex needs. Earlier this year, a woman known online as ‘Sheffield Keeley’ was found dead in the street of an overdose (though in many ways she had been hounded to her death by so-called ‘content creators’ who had relentlessly bullied her online for clicks.)

The using area at The Thistle, Glasgow.

NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde.

Her early death was just the most publicised of many. In November last year, a sobering piece by The Tribune’s Dan Hayes outlined the scale of Sheffield’s drug death epidemic, especially since a class of extremely powerful and dangerous synthetic opioids called nitazenes started entering the market.

But instead of being given the support they need, the most vulnerable people in our city are being targeted with renewed force. Recently, Sheffield City Council introduced a Public Space Protection Order (PSPO) in the city centre, which appears to have been designed to criminalise begging and rough sleeping as well as drug and alcohol addiction.

The aim of the PSPO seems to be to push rough sleepers to the margins, out of sight of the tourists and business visitors the council is openly courting. But anyone who lives near Castlegate will know it hasn’t been a success even on its own morally objectionable terms: the policy has had no noticeable impact on the number of vulnerable people in distress in the area.

Flowering thistle

Another British city has taken a very different approach to tackling drug deaths on its streets. Instead of Sheffield’s ‘out of sight, out of mind’ approach, Glasgow has instead chosen to tackle the issue head-on with an innovative, UK-first project which supporters say is already saving lives.

In recent years Scotland’s biggest city has had the grim distinction of being the drug death capital of Europe. Despite slight falls in recent years, in 2022 Scotland still had the highest number of drug deaths per capita in Europe by far, with Glasgow’s rate being twice the Scottish average.

The tougher that they’re coming down on drug-related crime, the more secretive people get

The team behind The Thistle hope to turn these figures around. A collaboration between the city council and the local NHS trust, the centre is what’s called a ‘safer consumption facility’, meaning people can inject illegal drugs using clean needles and under the supervision of medical staff.

The idea is that any overdoses can be treated immediately, using drugs like Naloxone which reverse the effects of an opioid overdose in an emergency. Sterilised needles provided onsite also eliminate the risk of drug users catching HIV by sharing injecting equipment.

By the end of June, 348 different people had used the service and there had been a total of 3,008 injecting episodes, with 39 medical emergencies during this time – all of them resolved safely. More than 100 safer consumption facilities have opened around the world since 1986, and there has never been a fatal overdose in any of them.

Supporters of The Thistle point to other benefits as well, including the ability for service users to get wraparound advice and support from medical staff while visiting the centre, and a reduction in the negative impact outdoor injection has on local communities in the east end of the city.

One harm reduction worker who works at the centre recently told STV that he estimates more than 30 people who have overdosed and been given emergency treatment at The Thistle would otherwise be dead in the six months since it first opened.

A plan for Bristol to set up England’s first Overdose Prevention Centre took a big step forward last week with a major meeting hosted by @TransformDrugs and Bristol University to discuss how it would work https://t.co/Gfh4jWI88j

— Anyone’s Child: Families for Safer Drug Control (@anyoneschild) July 21, 2025

The Thistle is the first (and so far only) legal safer consumption facility both in Scotland and in the rest of the UK, and was only able to open its doors in January following special legal dispensation from Westminster as part of a three-year pilot.

Supporters of The Thistle point to its modest cost, at only £2.3 million annually, despite being open from 9am to 9pm every day of the year. The cost of the service is so low that Saket Priyadarshi, associate medical director at Glasgow NHS, told The National that if only a few service users are prevented from catching HIV a year, The Thistle will have paid for itself due to the costs of lifelong treatment.

Dave Tebbet, a harm reduction lead at drug reform charity Transform, told Now Then that safer consumption facilities would be “effective in every city and every town within the UK,” adding that they “create an environment where you’re humanising people”.

“The secrecy that’s involved in drug use is incredible,” he said. “The tougher that they’re coming down on drug-related crime, the more secretive people get. People will go into unhygienic environments, they’ll be looking over their shoulder because the police may go past – they’ll be in a rush.”

“The fact that a person can’t take the time, and might not actually be using sterile equipment, is a contributing factor to the alarming drug-related deaths that we’re seeing year on year.”

Angela Argenzio of the Sheffield Green Party described the rise in drug deaths as “very concerning”.

Sheffield Green Party.

Councillor Angela Argenzio, leader of the Green Party group on Sheffield City Council, told Now Then that the rise of drug-related deaths among vulnerable people in the city is “very concerning.”

“The positive example of the introduction of drug consumption rooms in Glasgow should not be ignored. Giving people battling addiction a safe place to take drugs will not only save lives but can be the first step towards rehabilitation and someone getting their life back on track.”

“The Green Party has consistently called for supervised drug consumption rooms,” she continued. “They are places where people can inject or smoke their own drugs, under medical supervision, in order to prevent fatal overdoses, transmission of HIV and Hepatitis C, and other health harms.”

Dope sick

Although there has only been a modest year-on-year increase in the number of drug deaths in Sheffield so far, local health workers are bracing for a massive increase as new synthetic opioids begin to flood the market – some of them a hundred times or more stronger than heroin.

“This is a public health crisis, and we’re at the very start of it,” Tebbet tells me. “We need to be more prepared – it’s certainly going to get worse.”

Two factors he points to are the Taliban’s recent decision to ban opium production in Afghanistan, leading to a rise in demand for synthetic opioids, and the fact that synthetics are an order of magnitude smaller than traditional opioids, making them easier to smuggle.

The work that’s going on with the police in South Yorkshire and Sheffield is absolutely brilliant

“In a business sense, why would somebody transport something the size of a shipping container all the way over through various different countries when you can get something the size of a matchbox that’s just going to do the same thing?” points out Tebbet.

“There’s no morality in the trade, but when it comes down to the individual that’s using, it can be the tiniest grain of sand of a synthetic opioid that could send them into overdose. And that’s presuming somebody has got a tolerance to opioids.”

The opioid market in the UK works differently to that in the US, which is in the grip of a full-blown epidemic. Over the course of 2023, a staggering 79,358 people died of an opioid-related overdose in the United States (around 24 per 100,000 of the population), compared to 2,551 in the UK (around 4 per 100,000).

The disparity can be explained by the highly corrupt relationship between pharmaceutical companies and healthcare providers in the US, meaning that widespread legal prescribing of powerful opioids like Oxycontin is often financially incentivised by drug manufacturers, causing people across the country and from all walks of life to become addicted.

Although opioids are used as painkillers within the NHS, pharmacies and hospitals are practised at tightly controlling their use, meaning that misuse and deaths are focused in the illegal street market – often involving people sleeping rough.

Much of opioid use in Sheffield is centred around the Castlegate area.

Now Then.

Available antidotes

The illegal nature of the UK market for powerful opioids means it is less visible, with users often injecting on their own and out of sight. As well as safer consumption facilities, another intervention that could reduce the number of deaths caused by overdoses, especially among people sleeping rough, would be increased availability of Naloxone.

Naloxone, the emergency antidote that reverses the effects of an overdose caused either by heroin or by synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, is not only used by staff at The Thistle to prevent deaths onsite – it’s also available for service users on a take-home basis.

The antidote drug can be administered as an injection or nasal spray, but scientists at King’s College London are currently developing a “wafer” form to be taken orally, which will be easier for opioid users to carry with them and administer themselves without training.

In December 2024, South Yorkshire Police (SYP) became one of the first forces in the country to provide officers with Naloxone (the decision to carry the nasal spray is optional, and any officers who do so are provided with training in its use). The force told Now Then that since December their officers have administered the drug seven times.

Last week, an SYP officer administered Naloxone to a man experiencing an overdose in Sheffield city centre, saying that it “had the desired impact as he started to breathe much deeper and he came round when the ambulance arrived, and they then gave him a second dose of Naloxone before taking him to hospital for further medical treatment.”

“Naloxone should be available absolutely everywhere,” said Tebbet, who pointed out that there hasn’t yet been a national roll-out, meaning that the decision to carry the antidote is up to each individual force. “There’s no doubt about it, it does absolutely save lives. The work that’s going on with the police in South Yorkshire and Sheffield is absolutely brilliant.”

“People have a right to know what they put in their bodies”

But while Tebbet advocates for further rollout of both safer consumption facilities and Naloxone, he wants to stress that these are only two components of a much more comprehensive set of measures needed to reduce drug deaths in the UK.

First, he advocates for Heroin Assisted Treatment, or HAT. Pioneered by the NHS in Middlesborough, HAT is provided to long-term heroin users who have not responded to other treatments, and sees staff administer medical-grade heroin to users twice a day in gradually smaller doses.

Once the drug use is under control, specialists from other agencies work with service users to help them rebuild their lives and integrate back into society. Research by King’s College has found HAT provides “substantial benefits” compared to conventional methadone-based treatment.

Decriminalisation is cost effective for everybody, but the main thing is it doesn’t wreck lives

Second, Tebbet calls for widespread drug checking – where anyone can get their drugs tested to see what’s in them, including at festivals and in city centres such as Bristol – and drug checking, where drugs confiscated, seized or left in amnesty bins are analysed in labs, and public alerts are issued about contaminated or high dose batches.

“Everybody needs to know what drugs are in circulation in which area, so alerts can be raised, so drug workers know what they’re dealing with, and because people who are using drugs have a right to know what they put in their body,” says Tebbet.

Of particular concern are knock-off ‘benzos’ like Xanax, which are often obtained through the dark web and which are increasingly contaminated with synthetic opioids. These counterfeits will often arrive in a faithful reproduction of the original packaging including a blister pack, making them indistinguishable from the real thing. People may turn to the dark web if their prescription gets cut short and they’ve developed a dependency.

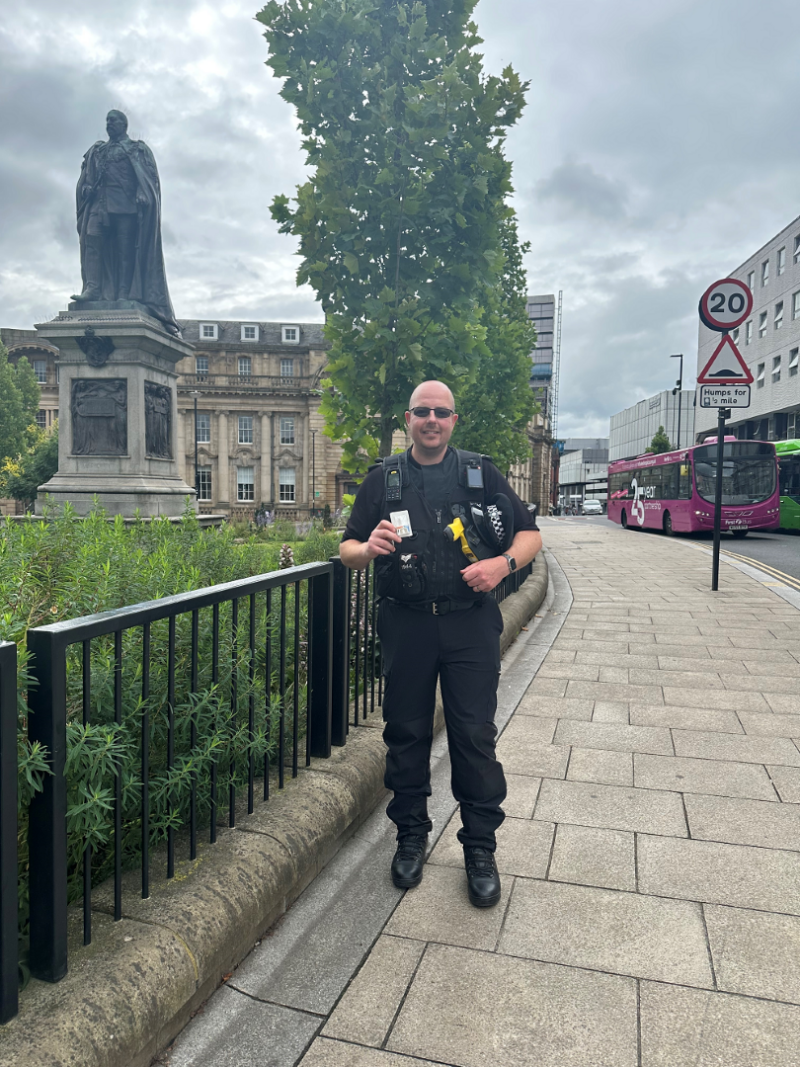

Sgt Simon Pickering administered Naloxone to a man suffering a drug overdose.

“The Diazepams that were going around not too long ago, there were huge amounts of non-fatal and fatal overdoses, and you could not tell to the naked eye that they were counterfeit,” says Tebbet. “The only way that you’d have been able to identify the contents of those substances is to get them tested.”

Harm reduction cities

Thirdly – and most radically – Tebbet calls for the decriminalisation of all drugs and the diversion of vulnerable drug users away from the criminal justice system, which studies around the world have shown does a vast amount more harm than good.

“[Decriminalisation] is cost effective for everybody, but the main thing is it doesn’t wreck lives,” Tebbet tells me. “Because even if somebody’s getting a caution for smoking a bit of weed in the park, that caution stays on their record depending on how hard someone is looking for it.”

“It can stop future employment, it can stop travel to places like America, New Zealand and Australia. And that criminal record will stay with someone for life.”

Decriminalisation is an approach pioneered by Portugal, where since 2001 drug misuse has been treated as a public health and where personal possession (but not distribution) of drugs is now a civil rather than a criminal matter.

Since the policy was introduced, drug deaths in the country, which once matched other European nations, have dropped significantly, and have stayed well below the EU average. In 2019, Portugal saw 40 times fewer drug deaths per head of population than Scotland.

The percentage of prisoners held on drug-related charges in Portugal has dropped from 40% to 15%, and perhaps counterintuitively, statistics also show that levels of illegal drug use have fallen significantly since decriminalisation, especially among young people. These rates are now consistently below the EU average.

‘People make choices – they may be very risky. The key thing is to keep them alive.’

I spoke to former prime minister of New Zealand @HelenClarkNZ after her tour of Glasgow’s drug consumption room. pic.twitter.com/qW1yzrCK3p

— Craig Meighan (@craigymeighan) July 3, 2025

Tebbet believes many of these interventions can be brought together by local leaders here in Sheffield under the banner of becoming the UK’s latest ‘harm reduction city’, following in the footsteps of Bristol, which has some of the highest drug death rates in England.

“The drug-related arrests and crime rate is high, but that could be shifted,” says Tebbet. “The numbers of people that are attending and successfully completing treatment will increase. It’s challenging the narrative, and the status quo and the stigma.”

Much of the meaningful work involved in turning this statement of intent into reality involves interventions outside the remit of drug policy, including taking a ‘housing first’ approach to rough sleeping and reducing overall inequality in society to lessen the chances of people ending up on the streets in the first place.

Research by The Equality Trust shows that drug use is more common in more unequal countries, and that in the US, states with high levels of wealth and income inequality also experience higher rates of addiction and more drug deaths.

But the main barrier to initiatives that aim to reduce the number of fatal overdoses in Sheffield may not be technical, medical or even financial – but political.

Some of the comments on Reddit under a recent Now Then article criticising the PSPO were so extreme in their use of dehumanising language about drug users that if they were broadcast on television, they would spark an Ofcom investigation.

While these attitudes might not represent the majority of the city, they indicate that a significant sector of the population do not see drug addiction as an illness but as a choice – and whose favoured solution would be to see vulnerable people cleared off the streets, or even shot. The approach taken to drug policy for more than a century simply has not worked, and requires both bravery and new thinking from leaders in cities like Glasgow, Bristol and Sheffield.

For Cllr Argenzio, who also chairs the council’s Adult Health and Social Care Policy Committee, the problem of Sheffield’s rising drug deaths isn’t one that can be addressed in isolation, but is inextricably linked to broader ideas around fairness and social justice.

“There is no simple solution to hard drug addiction, and addressing the reasons why people fall into it is what is ultimately needed,” she tells me. “This would mean addressing the profound inequalities in our society.”

We asked the local Liberal Democrat, Reform UK and Labour parties for comment on this piece. The Lib Dems declined to answer, and we did not receive a response from either Labour or Reform UK.

We also tried to speak to council officers working in public health for this piece. We were told by the council’s press team that we could not do this because we were also quoting councillors speaking in a political capacity, and that this would go against their media protocol.

Thank you to Dr Alex Corner for helping with some of the maths in this piece.