Cor Vos

Power data reveals how brutally hard pro racing is, but without context, it’s hard to grasp just how far out of reach those performances are for even the strongest amateurs.

Most of us never ride the same roads as the pros, let alone under the same conditions, making it hard to appreciate just how extraordinary, and out of reach, their performances really are. That is what makes l’Étape du Tour so insightful.

Organised by the same team behind the Tour de France, l’Étape is a one-day gran fondo that mirrors one of the race’s hardest mountain stages each year. It puts thousands of amateurs onto the same route the pros will tackle, and importantly on a closed course, offering a unique chance to compare performances.

In 2024, that meant Stage 19 was a brutal Alpine test with over 4,000 metres of climbing. Held a week before the Tour arrived, and with shared power data available, we can now place amateur and pro efforts (almost) side-by-side.

So how did they compare? We’ll dig into the numbers, speed, power, pacing, and finish times to find out. Where do the gaps show up, and did any amateurs hold their own and keep up with the peloton? Can a strong amateur come close to pro-level performance on the same roads? Spoiler: not really.

An asterisk: The route wasn’t quite the same

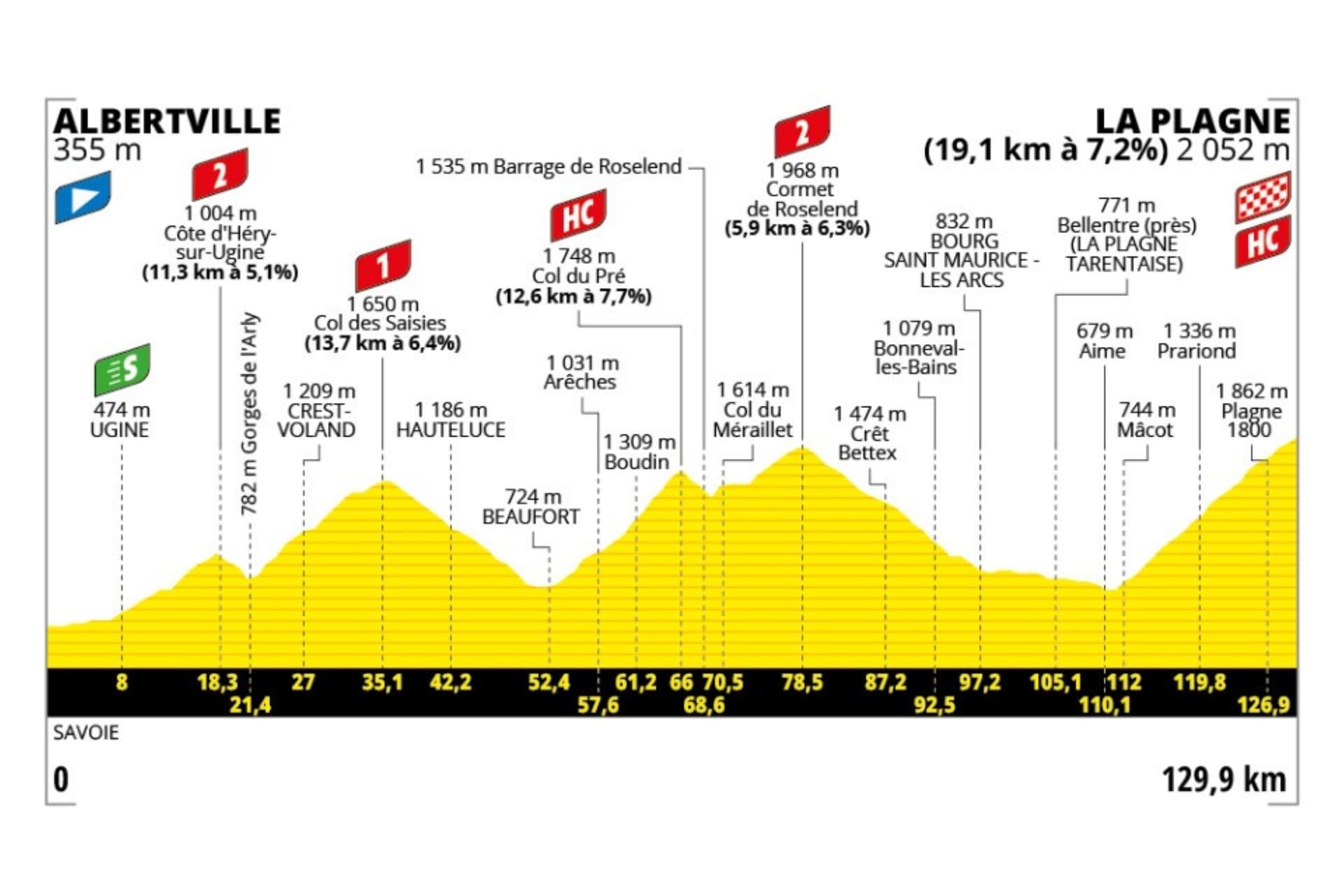

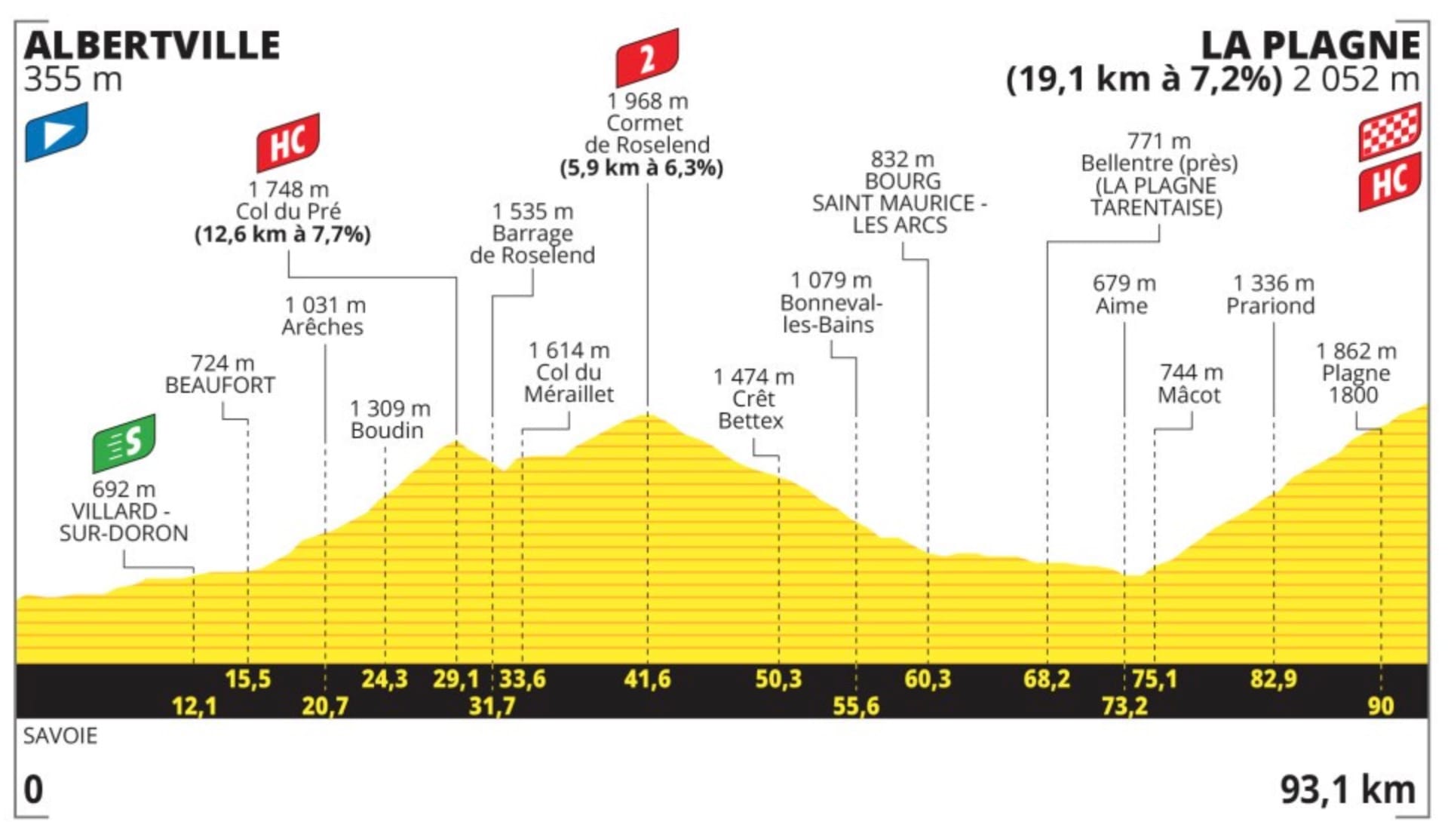

Even on its original route, Stage 19 was the shortest road stage of the Tour at just 129.9 km, but it packed a staggering 4,629 metres of climbing. L’Étape followed this full version, but due to an outbreak of Bovine Nodular Dermatitis, the Tour stage was altered at the last minute. Two early climbs were cut, reducing the route to 93.1 km and 3,400 metres of elevation gain.

The Tour route (right) ended up being cut short by 36.8 kilometres, missing the first two climbs from the Étape route.

Despite the shorter Tour stage, both routes remained brutally selective. Heading out from Albertville, l’Étape riders faced five categorised climbs before finishing atop La Plagne. A glance at the profile confirms it: there was virtually no flat riding. Unlike other gran fondos that frequently include valley sections to link the cols, this route stacked climbs with a break only before the final climb to La Plagne.

Out of the 129.9 km in l’Étape, 62.6 km (48.2%) were uphill. That means little chance for recovery and almost no opportunity to hide. And for the pros, there’s the added pressure of the time cut. The time cut is expressed as a percent of the winner’s time on a given day and varies according to both the average speed and the difficulty of the stage. Outside of the time trial stages, Stage 19 featured the most generous time cut in the Tour, but the pros still needed to cross the line within 21% (or 35 minutes) of winner Thymen Arensman’s time of 2:46:06, a reality that chased behind them up every climb.

It’s close, but it’s not a level playing field

Beyond the last-minute changes to the route, it is worth noting the obvious before we jump into the numbers. Both l’Étape and Tour might tackle the same climbs, but the condition in which riders arrive at the start line varies massively.

For most amateurs, l’Étape is the culmination of months of preparation, training, fueling, and tapering to be in the best possible form they can be on the day. In contrast, the pros arrived with 3,000 km of racing in their legs, including the hardest day in the race, a high-altitude Alpine stage with 5,600 metres of climbing, the day before.

The day prior to Stage 19, the Tour had tackled another Alpine test with more than 5,500 metres of elevation gain.

The day prior to Stage 19, the Tour had tackled another Alpine test with more than 5,500 metres of elevation gain.

After 18 days of racing, the Tour de France peloton was a long way off feeling fresh as it set off on the final mountain day. The cumulative fatigue cannot be ignored and highlights the performances on display. For most amateur riders, the concept of riding at all the day after more than 5,500 metres of elevation, at high altitude, would not be worth consideration.

Finding a true amateur benchmark

The whole concept of this piece was to illustrate the gap between exceptional amateur riders and the best in the world. However, l’Étape du Tour is an event open to anyone, and as a result, plenty of club pros or riders with recent pro experience take to the start line, making it difficult to pinpoint who is and isn’t an amateur.

To make things simple, I employed a simple rule to decide who does and doesn’t qualify as an amateur rider. If a rider has a profile on PCS (Pro Cycling Stats), I consider them a rider of a sufficiently high standard to eliminate their consideration as an amateur rider.

As a result, the first rider who met this criteria to cross the line at La Plagne was Vince Mattens. Ahead of him were four riders, all of whom have PCS profiles. In the interest of showing the full image from l’Étape, for each segment analysed below, I have included the fastest rider across that portion of the course (who in some cases is different than the top overall finishers), as well as Mattens’ time. Likewise, with the pros, I have included the fastest rider on a given segment (of those who upload files to Strava), and the fastest rider who published/disclosed power data.

Climbs 1 and 2: The climbs before the Tour stage

The first test on the route was the shallowest climb of the day. Over its 11.3 km length, the Cat 2 Côte d’Héry‑sur‑Ugine gains 576 metres at an average gradient of 5.1%, topping out at 1,004 metres. This begins just seven kilometres into the stage, giving riders at l’Étape very little time to settle into the task at hand.

This post is for paying subscribers only

Subscribe now

Already have an account? Sign in

Did we do a good job with this story?

👍Yep

👎Nope