US president Donald Trump’s August 1st tariff deadline has been hanging over the global trading system and Europe’s transatlantic trade with the US for months.

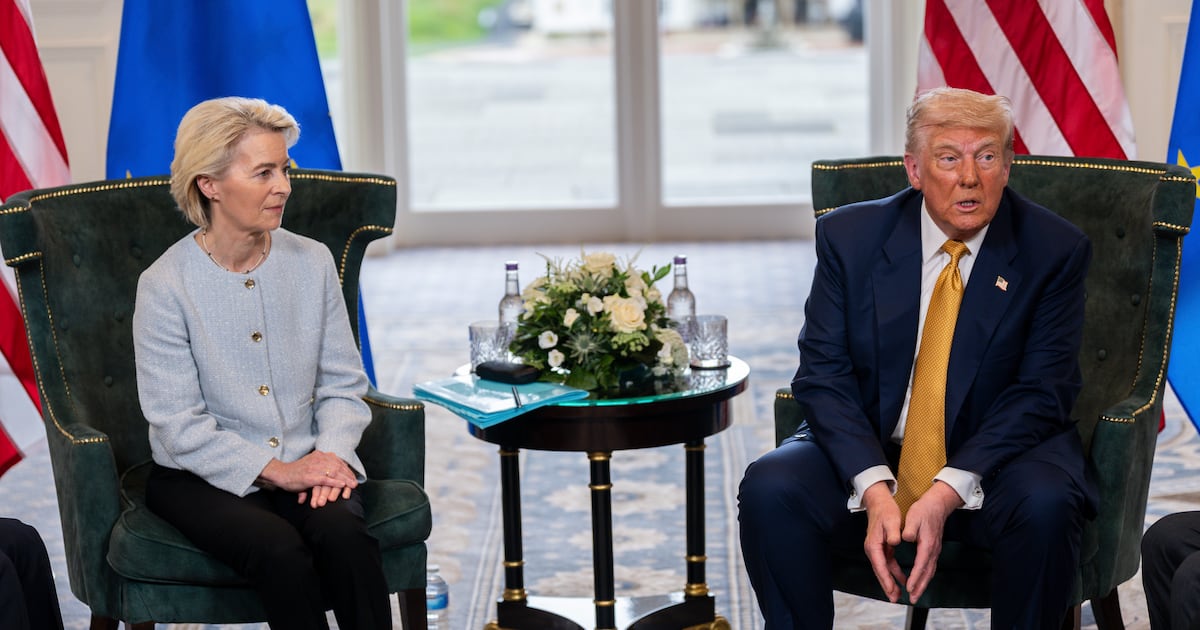

The deal struck by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and US President Donald Trump last weekend puts an end to a lot, but unfortunately not all, of the speculation.

Much of the detail has yet to be ironed out and there is still confusion over how certain parts will work in practice. For example, a “fact sheet” published by the White House seems to suggest the tariffs on pharmaceuticals and semiconductors will be paid by the EU when in fact they will be borne by US businesses and consumers.

Is there something in this deal for both sides?

On paper and despite the positive spin coming from Brussels about “trade certainty”, it’s a very a one-sided deal in favour of the US.

It imposes, from Friday, a baseline 15 per cent tariff on most EU exports into the US, including approximately €70 billion worth goods exported from Ireland, while committing the bloc to major purchases of US energy and armaments.

The EU, for its part, has reduced its tariffs on most US imports, in some cases to zero, giving US exporters much greater access to Europe’s 450 million-strong consumer market. This is far cry from the zero-for-zero deal initially offered by Brussels.

Based on last year’s trade figures, the deal might be expected to net the US government roughly $90 billion in tariff revenue.

What will it mean for the Irish economy?

For a small, export-led economy that relies heavily on trade with the US, it’s undoubtedly a negative. But Government ministers are playing up the fact that it avoids the 30 per cent tariff rate initially threatened by Mr Trump, keeps the trade doors open and avoids a mutually destructive trade war.

Critics will say the EU gave in too easily and that it failed, as gatekeeper to the most lucrative consumer market in the world, to wield its economic might. According to one estimate, the tariff deal will knock 0.5 per cent off EU GDP (gross domestic product).

What has been the reaction from Irish business?

“Irish exporters and importers will not have to operate under cumbersome and very expensive WTO [World Trade Organisation] rules. However, there will still be changes and increased costs to trade,” the chief executive of the Irish Exporters Association, Simon McKeever, says.

Employers’ group Ibec says a 15 per cent tariff represents “a substantial burden for many industries” and has called on Government to consider providing supports to vulnerable businesses similar to those rolled out during Brexit.

Does that mean an economic slowdown here?

On the basis of a 10 per cent tariff on EU goods exports to the US with an exemption for pharmaceuticals, the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) had forecast the economy here would grow, in modified domestic demand terms, at a slower rate of 2.3 per cent this year, down from 3 per cent previously.

Now that the actual deal involves pharma and a higher baseline tariff rate, the slowdown in headline growth is expected to be larger though not enough to trigger a recession.

The Government’s budgetary numbers, which are also based around a 10 per cent tariff rate, may also have to be scaled back.

Does the different tariff rate in Northern Ireland present a problem?

The divergence in tariff treatment between the EU and the UK (15 per cent versus 10 per cent) will also create cost differentials and other issues on the island of Ireland, between Northern Ireland and the Republic, particularly in areas like food and drink which will play out in way we perhaps can’t see at this stage.

Will the deal damage inward investment here?

The nightmare scenario for Ireland would be for an Apple or an Intel to up sticks and leave in the face of Trump’s protectionist agenda.

There’s no way of telling how these policies are influencing decision-making in the boardrooms of these companies. Like everyone else, they are probably adopting a wait-and-see approach.

The Government will hope that the increased cost of trading with the US (from Ireland) doesn’t outweigh the attraction of the Irish economy for US business.

What else?

Of course, the big question surrounding Trump’s protectionist trade agenda is how will it impact the US economy. A major slide in performance there – with tariffs expected to lead to higher prices for US consumers – and the global economy (including Irish exports) could suffer.

Trump is already hounding Federal Reserve boss Jay Powell to reduce interest rates to cushion any impact of tariffs but with inflation ticking up, that’s unlikely.

And, as always, there will be continued uncertainty over whether the US president will stick by this accord or decide that other action is needed.