Manchester is a city that never stops moving. With trams clanging by and towers rising on every skyline, it’s easy to forget the layers of history beneath your feet, layers filled with eccentric visionaries, radical women, Victorian oddities, forgotten murders, and statues that speak to struggles we’re still reckoning with today.

Luckily, historian Paul Chrystal hasn’t forgotten.

In his new book, Manchester: Secret & Strange Places to Visit, Paul invites readers to uncover the overlooked corners of Manchester’s past, places that don’t always make the tourist guides, but offer deep insight into what shaped our rebellious and resilient city.

We sat down with him to talk about his 10 favourite secret or strange stories, favourite people and the weird, wonderful, and often moving truths they reveal about Manchester’s soul

Exploring Manchester’s Secret & Strange Places to Visit

1. The Manchester Mummy

Harpurhey Cemetery (burial); originally displayed in Manchester Natural History Society Museum

At the top of Paul’s list is perhaps the strangest story in the entire book: the tale of Hannah Beswick, a wealthy 18th-century woman from Oldham who was so terrified of being buried alive that she made arrangements to be kept above ground after death.

“She had what’s called ‘taphephobia’,” explained Paul, “a pathological fear of premature burial. Back then, it wasn’t entirely irrational, people did get buried alive. But Hannah went to extremes.”

After she died in 1758, her body was embalmed, possibly with a mixture of turpentine and vermilion, and stored in an old grandfather clock case in her doctor’s home. Visitors came to gawk at her like a morbid museum exhibit. When her doctor died, the corpse was moved to the Museum of the Manchester Natural History Society, where she became a celebrity once again, displayed next to Peruvian and Egyptian mummies.

“She was on display for over a century,” said Paul. “It wasn’t until 1868 that she was finally buried.”

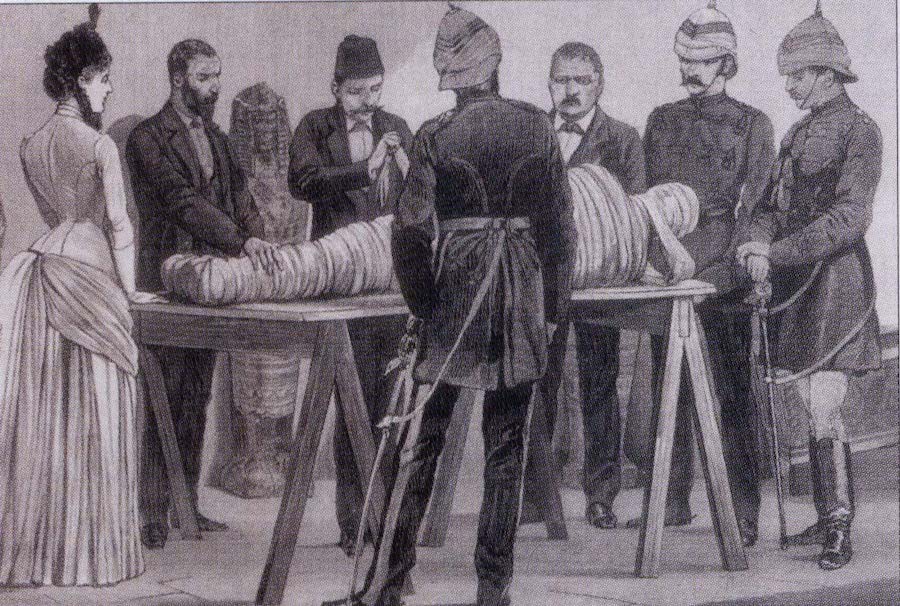

2. Optography: the murder victim’s eye camera

Referenced in 1880 Harpurhey murder case

One of the more bizarre entries in the book is a slice of Victorian pseudo-science that once played out right here in Manchester: optography, the belief that the human eye might record the final image it sees before death, like a natural CCTV camera.

In January 1880, an 18-year-old servant girl named Sarah Jane Roberts was murdered in Harpurhey. Newspapers reported that police examined her eyes in the hope of finding an image of the killer, perhaps burned onto the retina.

“It’s completely discredited now, of course,” said Paul, “but back then, they took it seriously. It was forensic science before forensics really existed.”

You won’t find an optography exhibit at a Manchester museum today, but Paul said interested readers should check out archives like the Manchester Police Museum or local libraries for articles from the Illustrated Police News of the era, “they were full of these creepy, lurid accounts.”

Lily Parr

Lily Parr

Statue at the National Football Museum

“She scored 900 goals and chain-smoked the whole way through her career,” Paul laughed. “Lily Parr was a trailblazer.”

Born in 1905, Lily Parr was one of the earliest female football superstars. She played in front of massive crowds in the 1920s, until the Football Association banned women from using FA pitches, effectively halting the women’s game for decades.

In 2019, she became the first woman to be honoured with a statue at the National Football Museum. “The statue’s not the strange part,” said Paul. “What’s strange is the FA’s decision to ban women from playing football for 60 years. And they’ve still never properly apologised.”

A timely opportunity to celebrate a trailblazer of the English game, especially after the Lionesses double Euro success last weekend.

Her bronze statue now stands proud in Cathedral Gardens, a reminder of how far women’s sport has come, and how much it still owes to pioneers like Parr.

4. ‘Adrift’: Manchester’s forgotten refugee statue

Adrift, by John Cassidy

Adrift, by John Cassidy

St Peter’s Square

You’ve probably walked past it dozens of times without noticing, but outside Manchester Central Library stands a poignant bronze sculpture of a family stranded on a raft, calling for help. It’s called Adrift, and it’s more relevant now than ever.

“It was made in 1907 by John Cassidy,” said Paul, “and it’s meant to represent the human condition, people clinging together in stormy waters, hoping for rescue. But today, you can’t help but see the resonance with migrants in the Mediterranean or the Channel.”

A father holds a sail aloft, a mother cradles her child, and the eldest son lies dying. It’s an image of desperation and dignity. “It’s one of Manchester’s most powerful statues,” Paul said. “And yet it’s barely talked about.”

5. FAC 251: The spirit of Factory Records

Charles Street, Oxford Road

Behind an unassuming façade on Charles Street lies a former musical revolution. FAC 251 is the spiritual home of Factory Records, the legendary label behind Joy Division, New Order, and Happy Mondays.

“It’s like Manchester’s own Motown,” said Paul. “Factory changed everything, how bands sounded, how they were marketed, how independent music worked.”

Even Tony Wilson’s headstone is part of the Factory catalogue, numbered FAC 501, making it the final official Factory “release.”

“It’s genius,” said Paul. “They turned an indie record label into a complete cultural movement. And FAC 251 is where it all started.”

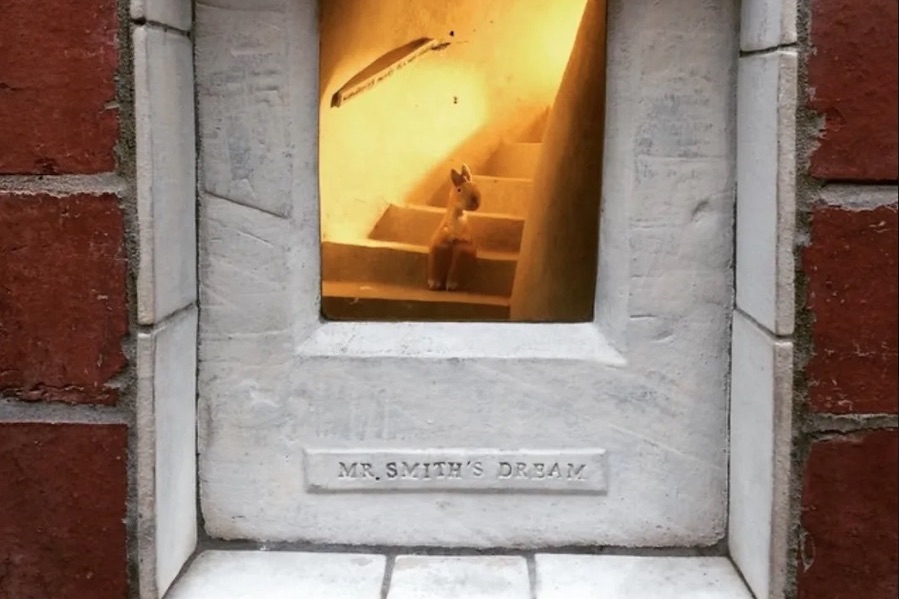

6. Mr Smith’s dream

Mr Smith’s Dream

Mr Smith’s Dream

Manchester Craft & Design Centre, Northern Quarter

If you stroll around the Manchester Craft & Design Centre, you might notice a tiny glowing staircase disappearing into the wall. Look closer, it’s Mr Smith’s Dream, a miniature art installation inspired by an old pet shop owner in the area.

“It’s easy to miss,” said Paul. “But once you see it, you’re enchanted. It feels like a portal into another world.”

Created by artist Liz Scrine, the installation nods to Manchester’s past, the Northern Quarter used to be full of small family-run pet shops. “It’s a beautiful little tribute to the city’s everyday dreamers,” Paul said.

7. Emily Williamson and the war on feathers

Emily Williamson

Emily Williamson

Fletcher Moss Park, Didsbury

In the late 1800s, women’s fashion was adorned with extravagant feathered hats, the more exotic the plumage, the better. But the birds paid the price, often hunted to near extinction.

Enter Emily Williamson, a Didsbury suffragist who launched a protest from her home, forming what became the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB).

“She was outraged by the slaughter of birds just for vanity,” Paul explained. “She and her friends pledged to wear no feathers, and started a movement.”

Her long-overdue statue was unveiled in Fletcher Moss Park in 2023. “It’s not just about birds,” Paul said. “It’s about how women changed society, often without getting credit.”

8. Hat Works: The museum of hats

Hat Works, Stockport

Hat Works, Stockport

Wellington Mill, Stockport

Just a short ride from the city centre to Stockport, Hat Works is the UK’s only museum dedicated entirely to hats and hat-making. And it’s much more exciting than it sounds.

“You think it’ll be quaint,” said Paul, “but it’s extraordinary, the machinery, the fashion, the history. Stockport was once the epicentre of British hatting.”

The museum features a reconstructed Victorian hat factory, a massive hat collection from around the world, and the chance to try some on yourself.

It also explains the origin of the phrase “mad as a hatter, hat-makers were exposed to mercury fumes, which caused tremors and mental illness. “It’s fascinating, and slightly terrifying,” Paul admitted.

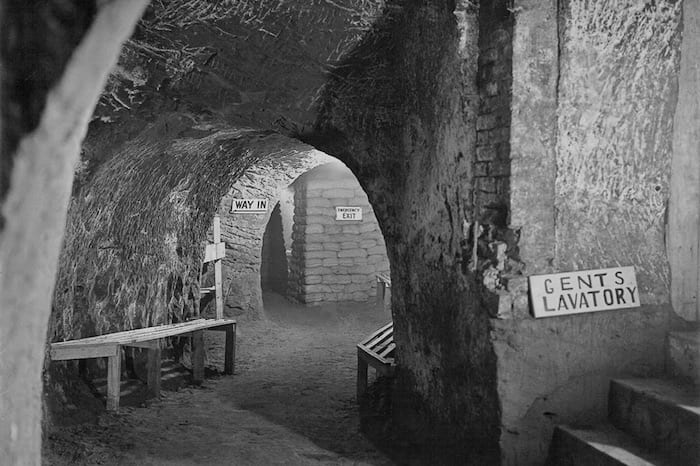

9. Stockport Air Raid Shelters

Stockport Air Raid Shelter

Stockport Air Raid Shelter

65 Chestergate, Stockport

During WWII, more than 6,000 civilians crammed into a mile-long network of tunnels dug into Stockport’s red sandstone cliffs to escape the bombs.

Today, you can visit those very shelters, and experience what life was like underground.

“It’s one of the most atmospheric places in Greater Manchester,” said Paul. “You walk through dimly lit tunnels, see the bunk beds, hear the air raid sirens. It’s not just a museum, it’s a time machine.”

They were nicknamed the ‘Chestergate Hotel’ because of their relative comfort: they had toilets, electric lights, even areas for nursing mothers. “And now they cost next to nothing to visit,” said Paul. “It’s a hidden gem.”

National Football Museum

Beloved BBC commentator John Motson may have become a national icon, but few realise he was born right here in Greater Manchester.

“One of his greatest lines came in 1977,” Paul said. “When Martin Buchan lifted the FA Cup for Manchester United, Motson quipped: ‘Fitting that a man called Buchan should be the first to climb the 39 steps.’ A perfect pun, classic Motty.”

His famous sheepskin coat now lives at the National Football Museum, alongside other treasures of the beautiful game.

Why should you read Manchester: Secret & Strange Places to Visit?

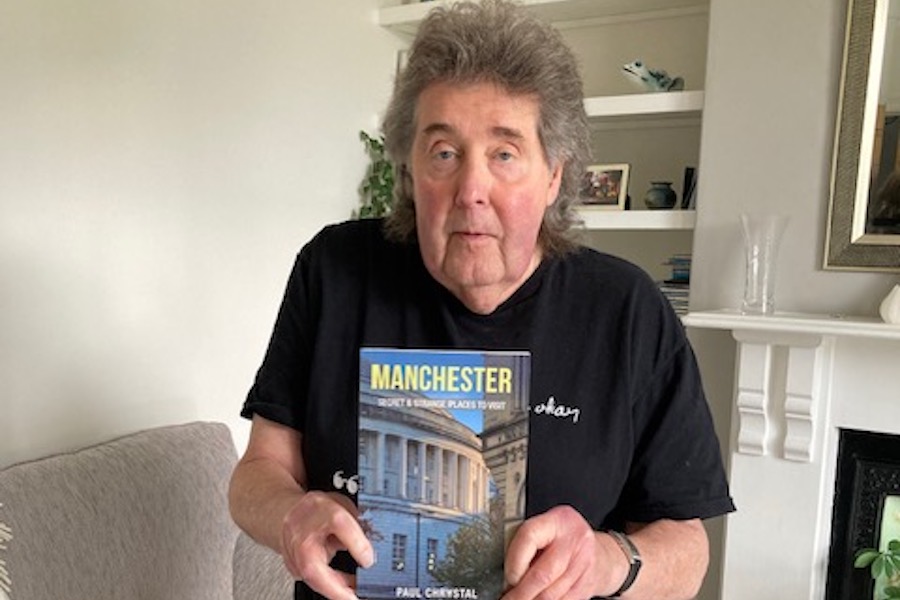

Paul Crystal and his new book

Paul Crystal and his new book

“Manchester is full of stories people think they know,” said Paul. “But there’s so much more beneath the surface. This book is for people who want to see beyond the obvious, to understand what makes this city truly great.”

His final word?

“You’re not meant to read it all in one go. Pick a page, pick a place, and go see it. You’ll come away with a new appreciation for how strange — and special — Manchester really is.”

Manchester: Secret & Strange Places to Visit by Paul Chrystal is out now. You can get your copy here