Analysis: Light pollution means experiencing a naturally dark night sky is becoming a rare experience

By Georgia MacMillan, University of Galway

In the space of five months in 2024, we experienced two of the most impressive Aurora Borealis displays of the last 25 years. These dazzling skyscapes were captured more widely than ever before, due to the improvements in smart phone camera technology and the immediacy of social media.

But not all Irish residents were able to enjoy the full splendour of the northern lights because some were left, not in the dark, but in the light. When used inappropriately or in excess, artificial light becomes light pollution and washes out the backdrop of a naturally dark sky, diluting the intensity of this natural phenomenon and, in some cases, masking it completely.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1’s Morning Ireland, Aengus Cox reports about the issue of light pollution

Experiencing a natural night sky is becoming a rare experience, and is much sought after by urban dwellers, in particular, who flock to remote places to experience dark sky tourism. The awe-inspiring visual experience of a truly dark sky is one of many benefits but there are other more compelling reasons to re-think light pollution such as wellbeing, wildlife impacts and the carbon cost of wasted energy emissions. However, the circadian clock is ticking and a night under the stars could be a thing of the past unless action is taken soon. Here are five major threats to Ireland’s remaining dark skies.

The Rebound Effect

As technologies provide more energy efficiencies, human nature has demonstrated that we consume more rather than less energy overall, negating the benefit of higher efficiency. This is known as Jevons’ Paradox or the Rebound Effect. When applied in the context of outdoor lighting, such efficiencies reduce the incentive to switch lights off and encourages the consumption of more ‘cheap to run’ lighting fixtures. Consequently, we are increasingly lighting up our homes and our gardens because we can, rather than because there is a need to do so.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1’s Today with Claire Byrne, travel writer Ed Finn and astronomer and telescope operator at Blackrock Castle Observatory in Cork Danielle Wilcox on dark sky tourism and discovering the sky at night

Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs)

The roll out of energy efficient LED technology is changing our experience of nighttime, creating bright as day scenarios in many areas. Early installations of LED lighting in the public realm opted for a bluer-white light in order to maximise energy efficiency, but blue light has a shorter wavelength on the lighting spectrum which is detrimental to both wildlife and human health.

Blue light also scatters more widely, particularly on damp and cloudy evenings, exacerbating the problem of glare from streetlights, sporting venues and from the headlamps of more modern motor vehicles. Fortunately, the efficiency of warmer coloured LED has improved considerably, offering energy-efficient choices to consumers and public authorities that are kinder to biodiversity and wellbeing, whilst also mitigating light pollution.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1’s The Business, satellites are now dotted across our skies, but are they ruining the stargazing experience? Siofra Mulqueen finds out

Mega Constellation Satellites

The excitement of seeing the International Space Station pass overhead has waned as mega-constellations of satellites such as Starlink launch in their thousands. Whilst these low Earth-orbiting satellites provide valuable societal services, scientists have voiced concerns on their unsustainable increase and contribution to space debris.

There is also their impact on astrophotography, radio astronomy and ground-based astronomical observation and the cultural heritage of a dark night sky. With estimates that there will be 400,000 commercial satellites launched by 2030, future night skies are set for an increase in artificial brightness as these mega-constellations streak across the sky.

Shifting Baseline Syndrome

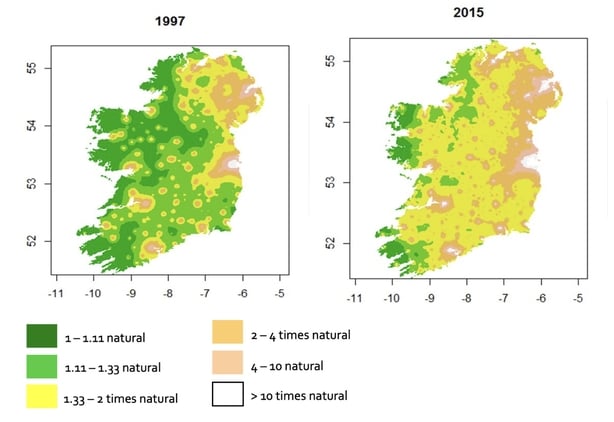

Ireland’s Atlantic edge sits at the last frontier of natural darkness in Europe, but we are losing this resource at an alarming pace, and it is happening while we are sleeping. Over the past few decades, light pollution has spread across Ireland, leaving few places with a view of a naturally dark sky overhead.

The growth of light pollution in Ireland. Source: Prof Brian Espey, Trinity College Dublin

Night sky horizons are blighted by skyglow, and it is likely that those born in the last 25 years have never experienced a truly dark sky from their own home. Without experiencing a naturally dark sky, there is no benchmark to measure sky brightening and consequently no empathy for its decline. This is known as Shifting Baseline Syndrome; a concept already recognised in discourse on the societal acceptance of the degradation in biodiversity.

Wind turbine lights

Meeting renewable energy targets is crucial for Ireland. However, the increasing allocation of wind turbines in remote rural spaces means that Atlantic horizons, previously cherished for their sunsets and uninterrupted views of the Northern Lights, will be significantly impacted with red lights as darkness falls. Light travels astronomical distances, which exoplains why we can see starlight from some places on Earth but also why Dublin is the biggest source of light pollution to the dark skies of North Wales.

Even at a distance, artificial lights in remote places disturb the last vista of a natural nocturnal environment and present potential hazards for migratory wildlife. Aircraft safety regulations require high structures to be lit at night, but there may be alternative solutions such as Aircraft Detection Lighting Systems. These radar detection systems trigger lights to be turned on when an aircraft is detected within the effective area and are now mandatory for wind turbines in Germany.

Solving light pollution is not quite as simple as a ‘flick of a switch’, but the societal benefits provided by a natural nightscape warrant more action and effort. We need to find solutions to mitigate the spread of unnecessary light waste across our skies.

Follow RTÉ Brainstorm on WhatsApp and Instagram for more stories and updates

Georgia MacMillan is a PhD student at the University of Galway and Mayo Dark Sky Park Development Officer, funded by the Irish Research Council/Research Ireland in partnership with the National Parks & Wildlife Service.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ