While the irony of Roger Daltrey singing “hope I die before I get old” as he enters his ninth decade has been mined to the point of cliché, nobody could have guessed in the Sixties that this one-time figure of rebellion would be bestowed with a knighthood. In 1965 Pete Townshend wrote the Who’s My Generation after the Queen Mother objected to the sight of his car, a Packard hearse, on the streets of Belgravia and commanded it be towed away. Now the man who sang Townshend’s words of defiance against the old order is to become a sir.

“It is weird,” says Daltrey, sitting at a wooden table in the garden of his house in Chiswick in west London, of being embraced by the establishment. “But it’s great for the charity, so I accept it on behalf of all the unsung heroes who have helped me with it. It will open doors.”

Since 2000 Daltrey has been staging annual fundraising concerts at the Royal Albert Hall for Teenage Cancer Trust, which was set up in 1990 to provide specialist units for young people suffering from cancer. Is that why he was given the knighthood? “Of course, but the honours system is in desperate need of updating. It’s a weird club to be a part of and I’m not entirely comfortable with it. Still, I’m not going to be here much longer. If I live another ten years it will be way past anyone in my family, and it’s important for Teenage Cancer Trust to continue. We were seeing teenagers put in wards alongside two-year-olds or geriatrics and the isolation was devastating. The environment of someone suffering from a serious illness is every bit as important as a good drug.”

Daltrey receiving his CBE in 2005 with his sister, granddaughter Lily and wife Heather

TIM CLARKE/ROYAL ROTA/GETTY IMAGES

Daltrey is a strange mix: a former Labour voter who now says that “Labour has made us a country for the f***ing scroungers”; a self-made millionaire with a dedication to charity and a reputation for generosity; a man who has spent the past six decades in a creative partnership with someone who couldn’t be more different. As Townshend told me in 2019: “I’m a Remainer, he’s a Brexiteer. I believe in God, he doesn’t.” Yet they have stayed together, surviving the deaths of the drummer Keith Moon and the bassist John Entwistle. Townshend and Daltrey are, rather like Noel and Liam Gallagher, the odd couple who need each other.

Now the partnership that has defined the Who since the 1964 single I Can’t Explain, Townshend’s tale of a young mod who wants to tell his girlfriend he loves her but can’t because he’s taken too many amphetamines, is coming to an end. The Who announced in May that they are to embark on The Song Is Over, their last tour of the US. Does this mean the end of UK concerts too?

“This is certainly the last time you will see us on tour,” says Daltrey, looking somewhat agitated at the prospect. “It’s gruelling. In the days when I was singing Who songs for three hours a night, six nights a week, I was working harder than most footballers. As to whether we’ll play [one-off] concerts again, I don’t know. The Who to me is very perplexing.”

• Roger Daltrey’s backstage diary — and a farewell to organising 24 years of concerts

Wasn’t the Who, a combustible entity formed of the tortured genius of Townshend, the stoicism of Entwistle, the wildness of Moon and the rock-god charisma of Daltrey, always perplexing? “Yes, but with all the potential future years in front of you, you could handle it. I’m going to be 82 next year. Fortunately, my voice is still as good as ever. I’m still singing in the same keys and it’s still bloody loud, but I can’t tell you if it will still be there in October. There’s a big part of me that’s going: I just hope I make it through.”

John Entwistle, Keith Moon, Daltrey and Pete Townshend in 1968

KING COLLECTION/AVALON/GETTY IMAGES

The main problem is the effects of contracting meningitis nine years ago. “It’s done a lot of damage,” he says. “It’s buggered up my internal thermometer, so every time I start singing in any climate over 75 degrees I’m wringing with sweat, which drains my body salts. The potential to get really ill is there and, I have to be honest, I’m nervous about making it to the end of the tour.”

He thinks he destroyed his hearing even before he joined the band, while working in a sheet metal factory in Acton when he was 16. At the Teenage Cancer Trust concert in March, he revealed that not only was he going deaf but he was losing his sight too. If he lost his voice, he told the audience, he would “go the full Tommy”. Unlike many rockers his age, Daltrey doesn’t use an Autocue. “There’s no point. Can’t f***ing see it!” he roars. How is his sight now? “Not good,” he replies, from behind tinted shades. “I’ve got an incurable macular degeneration.”

• Pete Townshend: ‘Fans are irritated I won’t just play Who hits till I die’

Nevertheless, he’s determined to give American audiences a great show, in part to thank them for raising the members of the Who out of the postwar malaise they grew up under. “I want to give the songs the same amount of passion as I did the first time round,” he says. “But it’s not easy when you’re dealing with a partner who can be ambivalent about it.”

Townshend has stated on several occasions that he doesn’t enjoy touring. “So he says until he’s out there — and he loves the money. But look at those early Who concerts. Every night was a war. That’s how we got the music across. We’re not going to turn into f***ing Abba overnight, are we?”

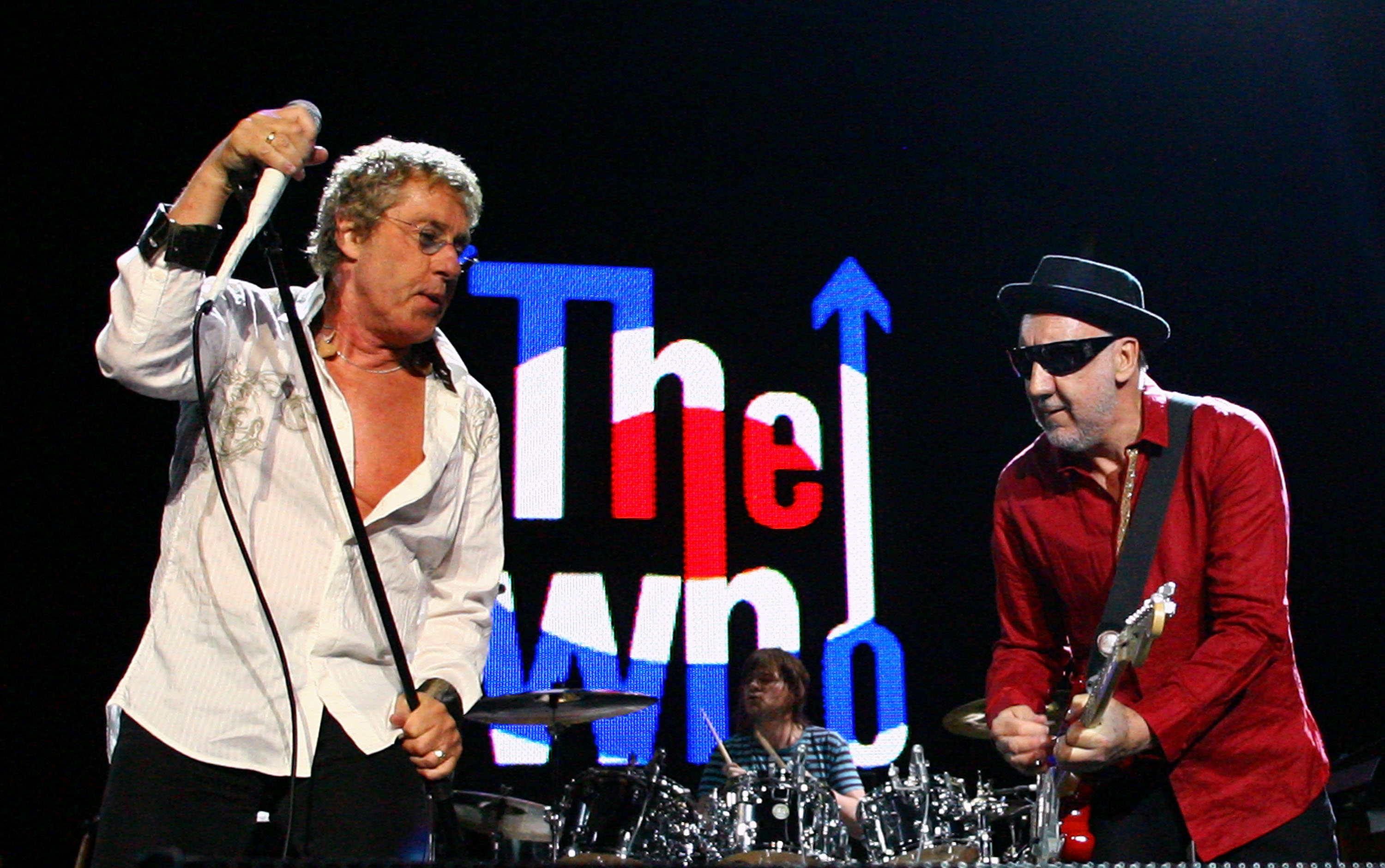

With Townshend at Wembley Stadium in 2019

SAMIR HUSSEIN/WIREIMAGE/GETTY IMAGES

They certainly aren’t, as proven by Daltrey’s well publicised issues with the Who’s former drummer Zak Starkey. The son of Ringo Starr was fired from the band in April, reinstated, then fired again two weeks later. What happened?

“An audience can see what’s happening on stage and have a complete misunderstanding of what’s actually going on,” says Daltrey, referring to the Who’s concert at the Royal Albert Hall in March, where the problems began. Starkey shot out a few barbs after the event. “What happened was I got it right and Roger got it wrong,” he claimed in an interview with The Telegraph, while on Instagram Starkey dismissed a statement that he retired from the Who as “total bollox”.

“It was kind of a character assassination and it was incredibly upsetting,” Daltrey says of Starkey’s remarks.

In fact, the whole thing started over a technicality. Daltrey explains that the drums used in a Who concert are electronic so that he can hear them through his in-ear monitors. “It is controlled by a guy on the side, and we had so much sub-bass on the sound of the drums that I couldn’t pitch. I was pointing to the bass drum and screaming at him because it was like flying a plane without seeing the horizon. So when Zak thought I was having a go at him, I wasn’t. That’s all that happened.”

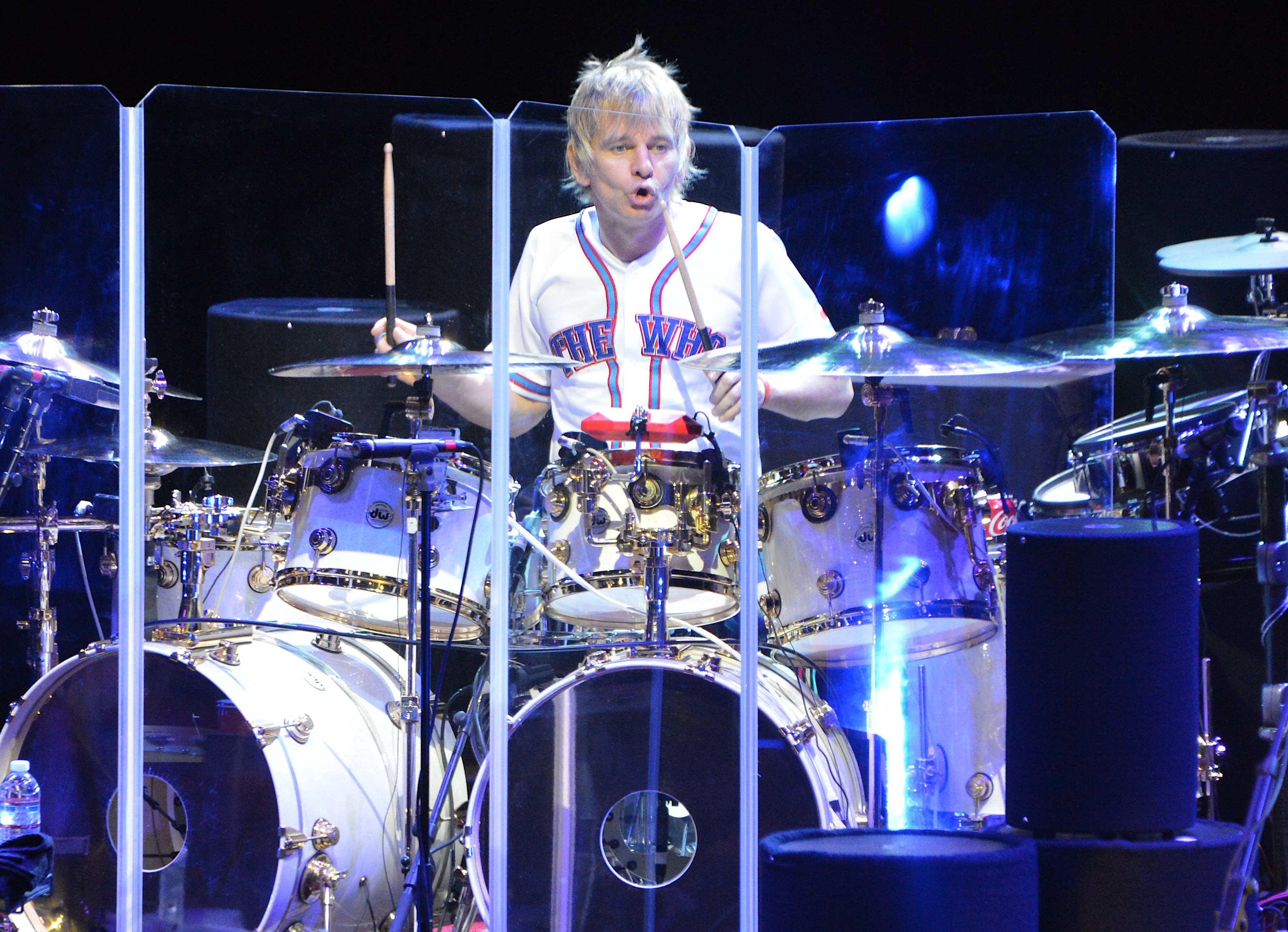

Zak Starkey performing with the Who in 2017

MINDY SMALL/FILMMAGIC/GETTY IMAGES

Then how come Starkey was back in the band, then out again? “Pete and I retain the right to be the Who. Everyone else is a session player. You can’t replace Keith Moon. We wanted to branch out and that’s all I want to say about it. But [Starkey’s reaction] was crippling to me.”

Not that life in the Who was ever easy. “John [Entwistle] was very funny, but he was a dark character with a vicious streak,” he says of the bassist. “He was brought up by his mum and a stepdad he didn’t like, and he was an addict who managed to survive for as long as he did. As for Moony [Keith Moon], sometimes you wanted to kill him but f*** he could be funny. Having said that, in today’s world where everything is banned — how dare you laugh! — a lot of things he did weren’t very funny if you were on the receiving end. But Moony was just a big kid, really.”

In late 1965 Daltrey got sacked from the band himself, albeit briefly, for beating up Moon after the drummer gave drugs to Entwistle and Townshend. “He used to hate me because I stood in front of him,” he says of Moon. “He wanted the drums on the front of the stage, so I used to get drumsticks in the back of the head. Despite it all, I cared about him.”

• The Who on a new album, ageing and artistic differences

Daltrey says that from 1968 to 1975 the Who changed music. He says he felt totally connected to Townshend’s writing, even if he didn’t always know what Townshend was going on about. Who’s Next, the band’s 1971 masterpiece and one of the greatest rock albums, was built round the aborted rock opera Lifehouse, a vision of an apocalyptic future where music is banned, pollution has rendered the outside world uninhabitable and citizens are connected to each other via an internet-like system called the Grid. When I ask Daltrey if he understood Townshend’s ideas for Lifehouse, he bursts into laughter.

“Pete’s ideas are a stream of consciousness without a thread of narrative, and that’s the problem,” Daltrey says. “I’ve always tried to help him find a thread, vocally and emotionally. With Lifehouse I said to Pete, ‘What the f*** is this about?’ He was into his religious thing at the time, so he was searching for the meaning of life and he said it might be found in a musical note. It was a mess of ideas and it didn’t make any sense. And he didn’t just want to make an album; he also wanted it to be a film. No chance!”

With Townshend in 2009

BRADLEY KANARIS/GETTY IMAGES

Nevertheless, Daltrey remains in awe of the guitarist and songwriter’s talent. “Tommy is the best opera ever written,” he decrees. “And I’ve seen a lot of the grand operas.”

For his part, Townshend says that Daltrey set the model for the golden-haired rock god — a look since taken up by Robert Plant and countless others. “It’s only because I didn’t get a haircut,” Daltrey says, guffawing wildly. “Couldn’t afford it. It wasn’t until ’68 that we got our first pay cheques. Up until then Keith Moon was spending it all.”

All these years later, Daltrey is determined to rock until he drops, whether the Who keep touring or not. “Never, never retire. You’ll be dead in three years. Daytime TV will kill you.” What is the most lethal programme, I ask… Cash in the Attic? “Oh, you’ve seen it have you?”

• Read more music reviews, interviews and guides on what to listen to next

The Who have 60 years behind them. What does Daltrey consider to be the band’s legacy?

“That’s a tricky one,” he says, after being momentarily, atypically stuck for words. “We ploughed our own furrow. We were not the pop of the Beatles or the bluesy connection of the Stones. All I can say is that we marched to our own drum.”

He thinks about this for a moment.

“And we had a madman on the drums.”

Roger Daltrey will perform at Dreamland Margate on Friday Aug 8. The Who are at Amerant Bank Arena in Sunrise, Florida, on August 16, then touring