Involuntary psychiatric hospitalization can put some people in Allegheny County on a path that leads to violence or death — outcomes that fly in the face of what civil commitment laws intended, new research has found.

The people at risk are those whose behavior may not be a clear-cut case for hospitalization, but are hospitalized anyway due to a doctor’s judgment call, often driven by risk-aversion and fear of liability. But instead of keeping these patients from harming themselves or others, hospitalization nearly doubles their risk of being charged with a violent crime in the months following their evaluation. It also nearly doubles their risk of dying by suicide or overdose.

The findings are detailed in a paper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and co-authored by one of its economists, a researcher based at Allegheny County’s Department of Human Services [ACDHS] and a fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. The research is likely the first to establish a causal link between hospitalization and harm a person experiences after they’re discharged, said Pim Welle, a co-author and the county department’s chief data scientist, during an interview.

“It was a surprising result for us to see because the goal of this statute is really to prevent harm,” Welle said, referring to Section 302 of Pennsylvania’s Mental Health Procedures Act, which empowers anyone to file a petition to involuntarily hospitalize a person whom they believe needs emergency psychiatric treatment. “That’s the justification for this thing, and we’re seeing these marginal cases break the other way.”

From left, Alex Jutca, director of the Office of Analytics, Technology and Planning and Pim Welle, chief data scientist, discuss AOT during an interview at the Allegheny County Department of Human Services, May 6, in Downtown. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

From left, Alex Jutca, director of the Office of Analytics, Technology and Planning and Pim Welle, chief data scientist, discuss AOT during an interview at the Allegheny County Department of Human Services, May 6, in Downtown. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

The research focuses on about 40% of the people involuntarily hospitalized in the county: those who would be committed by some doctors — who may be more likely to uphold petitions — but would not be committed by others. The sample is made up of involuntary hospitalization evaluations of people aged 18 to 64 that took place here from June 2014 through the end of 2023. Welle emphasized the results can’t be generalized to the total population of those involuntarily hospitalized in the county.

“The last thing that we want people to take away from this study is that we should get rid of this 302 system — that would be a tragic conclusion if people understood that from our work,” he said. But the data suggests “we should dial back” the amount of cases that fall into a gray area.

The paper was published this month during a time of increasing political support for involuntary commitment. President Donald Trump signed an executive order Thursday that aims to institutionalize unhoused people who have mental illnesses, substance use disorders or both. The impact is unclear because states make laws that regulate involuntary commitment and programs are administered by county and local governments. The order also directs federal agencies to shift funding away from housing-first and harm-reduction programs, which are supported by evidence. “Shifting homeless individuals into long-term institutional settings for humane treatment through the appropriate use of civil commitment will restore public order,” the order said.

Many states, including Pennsylvania, have expanded involuntary commitment laws over the past decade, though implementation has been limited. Allegheny County’s top human services official, Erin Dalton, informed the state in December that the county will implement Pennsylvania’s statute for assisted outpatient treatment [AOT] by this fall, though she told Public Source in May that a final decision hasn’t been made. AOT is a controversial legal mechanism for forced treatment in the community, which human services officials are considering as part of a plan to mitigate the poor outcomes of involuntary inpatient commitment described in the working paper. The evidence for AOT is mixed and no Pennsylvania county has successfully implemented it since it became state law in 2018.

What’s it like to be involuntarily hospitalized?

Cassandra, a 34-year-old native of Long Island, New York, was first involuntarily hospitalized as a teen. At her request, Public Source is withholding her last name to keep her diagnoses of depression and schizoaffective disorder private. She said she “struggles with paranoia” and “gets overwhelmed very easily,” among her other symptoms.

She witnessed and experienced constant domestic violence in her household while growing up. That triggered an outburst when she was 19 that led her parents to call the ambulance that took her to a local hospital. She described an overwhelmingly negative experience during the three months she spent in its psychiatric unit: Hospital staff wouldn’t take her off the antipsychotic risperodone, despite her complaints about its side effects. “I had to pull my pants down and get injected in the behind” by male hospital workers, she said, which traumatized her so much that she punched a window.

“The hospital that was treating me mistreated me,” she said. “The staff members were just very disrespectful.”

The paper’s findings are unique to conditions in Allegheny County and can’t be tied to Cassandra’s experiences in another jurisdiction. But an expert who wasn’t involved in the study said too many patients like her lose trust in the mental health care system after such bad experiences.

What happens to people while they’re hospitalized “is just this black box that goes unexamined,” said Morgan Shields, an assistant professor in the School of Public Health at Washington University in St. Louis. Her research focuses on that quality of inpatient psychiatric care, including how institutional betrayal can affect trust and engagement with systems.

A heart hangs in one of the windows of UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital, July 24, in Oakland. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

A heart hangs in one of the windows of UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital, July 24, in Oakland. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

“We really need to be thinking about what’s happening inside of that black box, and how much of this effect is due to” force, disruption and what’s happening overall to people in hospitals, said Shields. “Those are outstanding empirical questions that, while this paper is a huge contribution, it can’t answer.” She noted the experiences of those who are committed “aren’t a monolith” and “some people have what they feel are really good experiences.”

“The therapeutic care that happens in inpatient [settings] has to outweigh” the cost of negative experiences in hospitals, Welle said, “but that’s not happening” for those who fall into the gray area where they would be hospitalized by some doctors, but not others.

Evidence that hospitalization can cause harm

The county’s uniquely robust data collection system allowed the research team to investigate the effects of involuntary hospitalization, Welle said. It integrated Medicaid records, court records, death notices, state unemployment insurance claims and data from other sources to create the dataset. (The team explained their research design in answers to these frequently asked questions.)

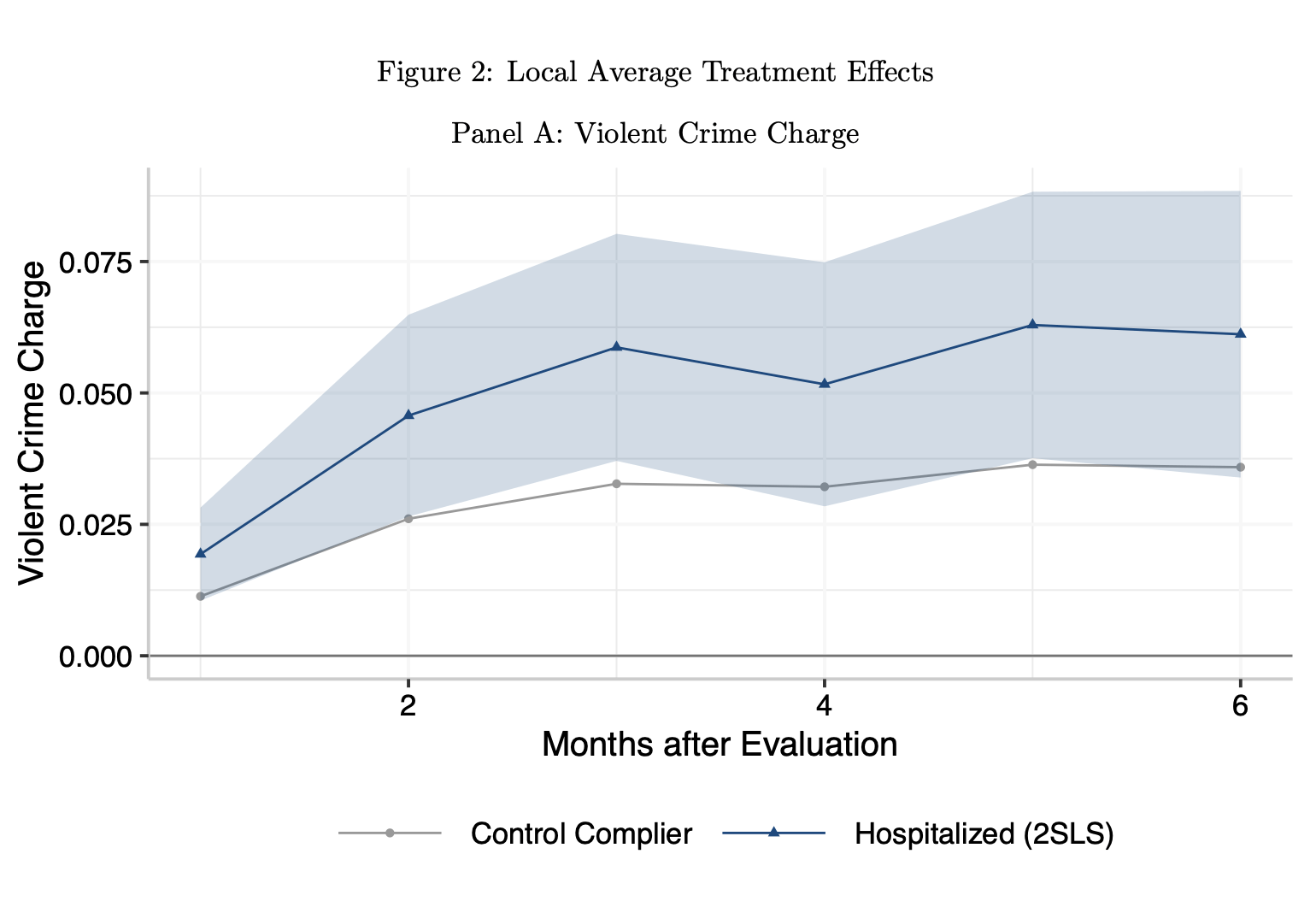

Physician tendency to hospitalize in the sample ranged from 11% to 100%, indicating some doctors were more likely to hospitalize those facing 302 petitions while others were less likely to do so. An increase in a doctor’s tendency to hospitalize was associated with an increase in a patient’s likelihood of being charged with a violent crime in the following three months.

The likelihood of a violent criminal charge was much higher for people who were involuntarily committed in borderline cases than for a control group. (Source: report co-authored by the Allegheny County Department of Human Services)

The likelihood of a violent criminal charge was much higher for people who were involuntarily committed in borderline cases than for a control group. (Source: report co-authored by the Allegheny County Department of Human Services)

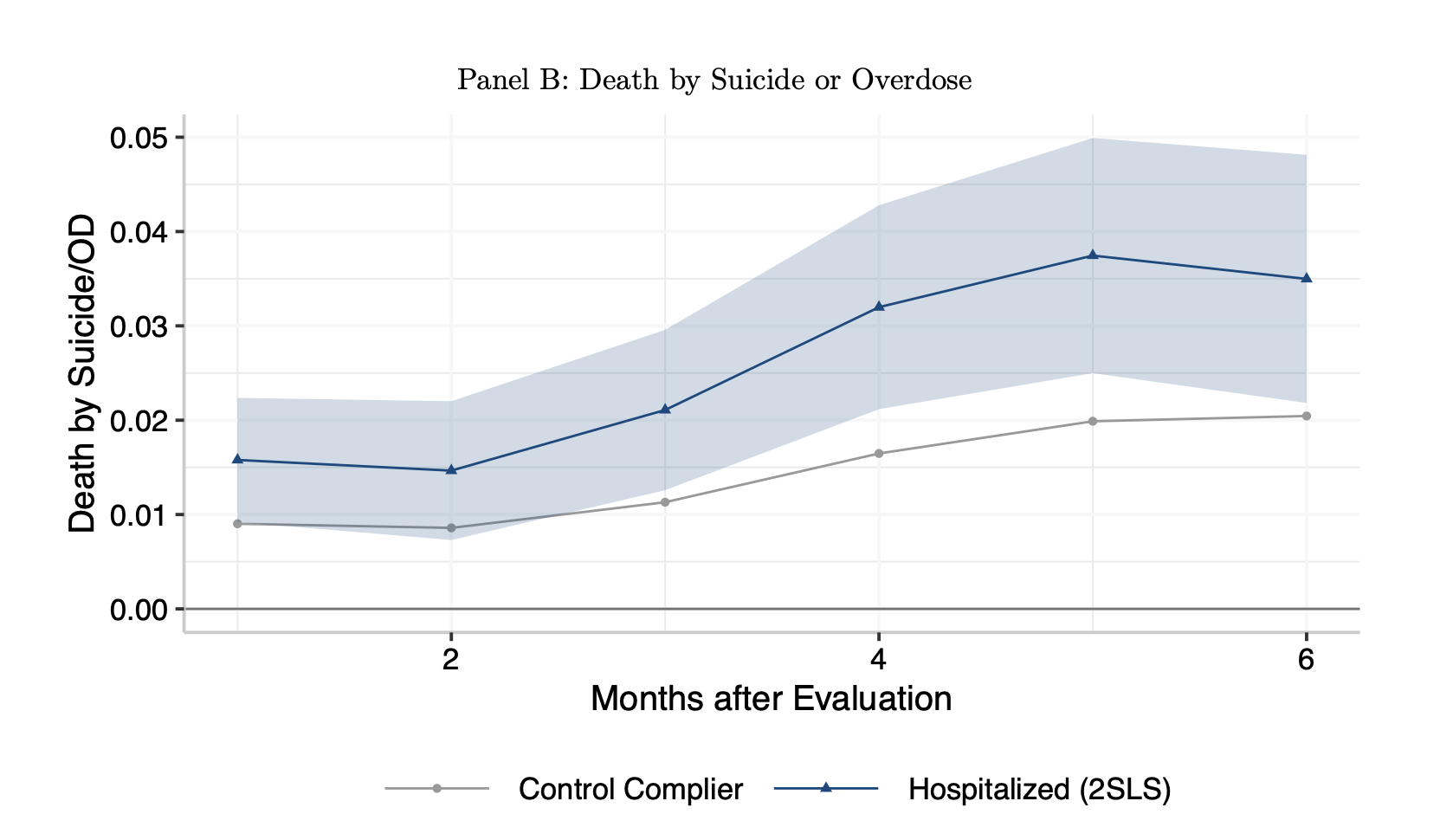

An increase in a doctor’s tendency to hospitalize was also associated with an increase in the probability of suicide or overdose death.

Similarly, the risk of death by suicide or overdose was substantially higher during the months after an involuntary commitment that was a judgment call than for a control group. (Source: report co-authored by the Allegheny County Department of Human Services)

Similarly, the risk of death by suicide or overdose was substantially higher during the months after an involuntary commitment that was a judgment call than for a control group. (Source: report co-authored by the Allegheny County Department of Human Services)

The team explored “mechanisms” that could be driving these outcomes, including the disruption of employment and access to housing, and loss of trust between the patient and the petitioner — who may be a loved one or a professional such as a social worker — and in the entire mental health care system.

The study also found that people subject to involuntary commitments included just 1.5% of the county’s Medicaid enrollees, but accounted for nearly 25% of Medicaid-paid behavioral health spending.

Some doctors fear liability

A psychiatrist told Public Source he initially didn’t want to believe the research findings.

“I was somewhat incredulous, and I felt that there had to be some other explanation for this increase in suicide, overdose and criminal charges we’re seeing,” said Awais Aftab, a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University, who spent several years working at a state hospital in Northfield, Ohio. “But the more I looked at the data, the more I cannot find some methodological limitation or some kind of confounding variable,” he said. “The data held up pretty well.”

Aftab — who once sat on a symposium panel with Welle — wrote a Substack essay about the findings, where he quoted from the book Skin in the Game by the statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb: “A doctor is pushed by the system to transfer risk from himself to you, and from the present into the future, or from the immediate future into a more distant future.”

“The real thing to do is that, if you’re in doubt, then discharge the person. Only admit them if you’re very sure that this is what they need right now.”

Awais Aftab

Aftab described a culture of “defensive decision-making” around involuntary commitments, motivated by a doctor’s fear of liability if a patient whose petition they didn’t uphold harms themselves or others in the community. When those doctors admit patients, he said, “they’re not thinking of what will happen three months down the road,” such as the adverse outcomes in the research. There could be tradeoffs between ensuring a person’s safety in the moment and ensuring their safety in the long-term, and physicians should be trained to navigate that, he added.

“The real thing to do is that, if you’re in doubt, then discharge the person,” he said. “Only admit them if you’re very sure that this is what they need right now.”

Aftab also attributed the study’s findings to a nationwide shortage in psychiatrists. They tend to hospitalize people at lower rates than emergency physicians less experienced in mental health, the researchers wrote in the report.

And physician bias against Black patients — who are disproportionately committed in the sample the researchers studied and nationally — could be playing a role, too. “Clinicians tend to perceive Black [patients] as being more dangerous and being more at risk,” he said.

What the county is doing to help those at risk

The study “should not have been possible,” said Alex Jutca, director of the Office of Analytics, Technology and Planning within ACDHS. He pointed out the health system failures that contributed to the harms experienced by those in the research sample. “There should not be sufficient variation in the [physicians’ decision-making] to allow us to estimate this.”

After the paper was published on July 15, the county’s Department of Human Services put out a statement that said it’s “committed to improving outcomes and reducing adverse events” for people with serious mental illness, and listed 11 policies and programs it’s implementing or considering. The plan includes:

- Working with providers to “reexamine physician training,” facilitate “knowledge-sharing across disciplines” and promote more circumspection around the choice to hospitalize

- Launching a new “peer-led, short-term respite overnight program” in a “home-like environment,” staffed by those with personal recovery experience who are trained to provide non-clinical crisis services

- Launching an “Alternative Response program,” which routes 911 calls to behavioral health first responders in lieu of police across 11 municipalities and two police departments

- Deploying multidisciplinary crisis response teams to key areas, including downtown Pittsburgh, to “meet people where they are,” offer to connect them to low-barrier care and reengage them frequently

- Expanding the supply of supportive housing for people with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders, with the goal of adding 300 beds this year.

The plan also includes two controversial proposals: AOT and a pilot program to test the efficacy of financially incentivizing people to adhere to psychiatric medication in the form of long-acting injectables.

UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital, July 24, in Oakland. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital, July 24, in Oakland. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

“Reexamining physician training” will require buy-in from the region’s large health systems. The research sample contained 424 physicians at 14 different hospitals, which likely includes UPMC and Allegheny Health Network facilities.

UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital in Oakland is a major provider of inpatient behavioral health services in the region. A spokesperson wrote that hospital officials discussed the paper’s findings with county human services officials.

“These nuanced situations underscore the importance of clinical judgment and specialized training in making informed decisions about each individual’s unique clinical status, and care needs,” they wrote, referring to people whose 302 petitions may be upheld by some doctors, but not others. They didn’t address a question specifically about new training initiatives, but said “UPMC is committed to working collaboratively with the county … and continuously evolving our practices to best serve the mental health needs of our individuals in our communities.”

An Allegheny Health Network spokesperson couldn’t immediately confirm its officials have seen the study and are in discussions with the county.

Independent experts weigh in on research and policy

Public Source asked researchers who were not involved in the study to evaluate its methodology and findings, and the county’s policy solutions. One praised the study’s findings, but criticized the county’s lack of investment in qualitative research that directly engages those who’ve been through involuntary commitment.

“I sent it to a bunch of people who were very excited to have such a paper,” said Nev Jones, an associate professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Pittsburgh. Jones is an expert on psychosis interventions and was awarded a contract by New York state to study the impacts of AOT there. Cassandra, who is under an AOT order, is a participant in the evaluation.

Nev Jones, an associate professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Pittsburgh, stands for a portrait on May 7, in Uptown. Jones is leading a large-scale study of the effects of AOT in New York State. She has lived experience of serious mental illness and opposes the implementation of AOT in Allegheny County. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Nev Jones, an associate professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Pittsburgh, stands for a portrait on May 7, in Uptown. Jones is leading a large-scale study of the effects of AOT in New York State. She has lived experience of serious mental illness and opposes the implementation of AOT in Allegheny County. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

The paper is a valuable contribution to the scientific literature on involuntary treatment, she said, but “the next step here is simply not more administrative data analysis. … It requires a deeper understanding of where the gaps are from the perspective of the people in question, and what is going wrong from the perspective of the people in question.” Methods could include interviews, focus groups or ethnography, such as ridealongs with mobile crisis teams.

Welle agreed that “data only gets us so far,” but the county needs to be “very careful” in its engagement with “individuals pretty soon after a traumatic event.” It’s why “really serious qualitative work here is a large challenge,” he said, noting the possibility of surveying people with lived experience, among other qualitative pursuits.

Jones and Shields also criticized the county’s inclusion of AOT and financial incentives for medication adherence in its policy plan, and described serious concerns around the ethics of and evidence behind these interventions.

“I think that [AOT is] quite an inappropriate conclusion” to draw from the research findings, said Shields, of Washington University. “I think, if anything, there should be increased skepticism about forced treatment.”

Venuri Siriwardane is the health and mental health reporter at Pittsburgh’s Public Source. She can be reached at venuri@publicsource.org or on Bluesky @venuri.bsky.social.

The Jewish Healthcare Foundation has contributed funding to Public Source’s health care reporting.

This story was fact-checked by Rich Lord.

Your gift will keep stories like this coming.

Have you learned something new today? Consider supporting our work with a donation.

We take pride in serving our community by delivering accurate, timely, and impactful journalism without paywalls, but with rising costs for the resources needed to produce our top-quality journalism, every reader contribution matters. It takes a lot of resources to produce this work, from compensating our staff, to the technology that brings it to you, to fact-checking every line, and much more.

Your donation to our nonprofit newsroom helps ensure that everyone in Allegheny County can stay informed about the decisions and events that impact their lives. Thank you for your support!

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.