Birmingham, England, is not necessarily the first place you would associate with a Doctor of the Church.

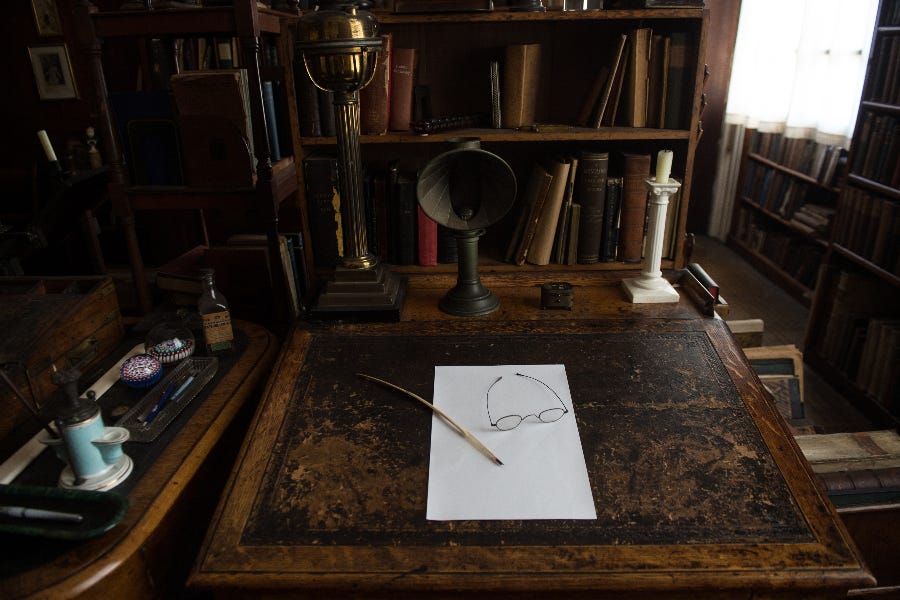

Newman’s glasses lie on his writing desk at the Birmingham Oratory in England. © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

Newman’s glasses lie on his writing desk at the Birmingham Oratory in England. © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

Broadly speaking, England’s second-largest city by population isn’t famous for its Catholic churches, shrines, and places of learning. These days, it’s arguably best known as the birthplace of heavy metal, for its shopping malls, and for having the U.K.’s largest Muslim population outside of London.

But there was a special joy in Birmingham July 31, when the Vatican announced that St. John Henry Newman would be declared a Doctor of the Church.

To learn more about why, The Pillar turned to Archbishop Bernard Longley, who has led the Archdiocese of Birmingham since 2009.

Not long after Longley’s appointment to Birmingham, Pope Benedict XVI visited the city to beatify Newman — the only beatification over which the German pope personally presided.

Like Newman, Longley was educated at Oxford University. Unlike Newman, Longley is a cradle Catholic. But the archbishop also has a deep familiarity with the Anglican Church of England from his decades of ecumenical work.

In May this year, Longley was elected vice president of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales. In June, Pope Leo XIV named him a member of the Vatican’s Dicastery for Promoting Christian Unity and, in July, a member of the Dicastery for Interreligious Dialogue.

The archbishop spoke with The Pillar in a phone interview Aug. 2. He discussed Newman’s legacy in Birmingham, the Anglican contribution to his acceptance as a Doctor of the Church, and how he hopes to celebrate the declaration.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Archbishop Longley with Pope Benedict XVI at the beatification of John Henry Newman in Birmingham, England, on Sept. 19, 2010. © Mazur/www.thepapalvisit.org.uk/CC BY-NC 2.0.

Archbishop Longley with Pope Benedict XVI at the beatification of John Henry Newman in Birmingham, England, on Sept. 19, 2010. © Mazur/www.thepapalvisit.org.uk/CC BY-NC 2.0.

St. John Henry had a keen awareness of the significant change happening in our country after the Industrial Revolution, and a real sense that his own mission should be in a place where he could serve as a Catholic pastor.

Littlemore in Oxford provided him with a retreat to prepare. It was the place where he was received into the Church. It’s a place of great beauty and significance, and indeed a place of pilgrimage.

But when he came to establish a life as an Oratorian and found an Oratory, after the example of St. Philip Neri, he clearly wanted it to be in a populous place, in a city, or place with a growing population.

He would have been aware of the demographic changes here in Birmingham, not least with the influence of migration from Ireland at that time. The Catholic community was largely expanding because of Irish migrants.

It is remarkable, and it’s an aspect of his universal appeal as a Doctor, that he was able to communicate in such a way with the local people, whose backgrounds and education were very different from his own. There was that commonality of faith that they saw in him, the holiness of a pastor and teacher.

When he settled in Birmingham, Newman brought another great gift to our city. I think that he was drawn here ultimately by the Holy Spirit, in a way which was entirely consonant with the priorities of his own life, not least in terms of education and wanting to deepen the faith of those who he served.

The Oratory Church in Birmingham, England, built between 1907 and 1910. © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

The Oratory Church in Birmingham, England, built between 1907 and 1910. © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

The first place in which he lived was outside the city. It would have been countryside then, in New Oscott. The house where he lived, Maryvale House, was the beginning of the Oratory community. But from that vantage point, which is high up over the city, he chose to come right into the heart of the city.

The first place he came to was Digbeth, which was very much an industrial part of the city — slum dwellings, small artisans’ dwellings all round, crowded in. They acquired an old gin factory. So they were surrounded by manufacturers of all sorts. The city was growing, and it was becoming what eventually became known as the City of a Thousand Trades.

The Industrial Revolution had changed the face of Birmingham. That meant the needs of local people were very different. There was tremendous affluence — the burgeoning middle classes, whose wealth was growing — but there was also great poverty.

People were attracted from the countryside, but also migrants coming from Ireland, to make their homes here and work in the factories. Newman would certainly have been aware of that. It was a time of great change in Birmingham, and he entered into that very enthusiastically.

Caption: A plaque commemorating Newman at Birmingham Oratory, pictured in June 2019. England © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

Caption: A plaque commemorating Newman at Birmingham Oratory, pictured in June 2019. England © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

The city continues to change. A lot of those factories have either been converted into flats [apartments] and dwellings, or they’ve been demolished and new dwellings have been put up.

When Cardinal Newman arrived in Birmingham, the city had no universities. Now it has four, one of which is Birmingham Newman University. It’s grown from about 1,500 students 15 years ago to 4,500 and growing toward 6,000.

The old gin factory’s foundations are still there in Digbeth. But more than anything else, perhaps, there’s the Oratory House, which he founded and helped to design, his library, and the Oratory Church. He didn’t, in fact, know the present Oratory Church, but it’s a memorial to him.

There’s also the seminary, St. Mary’s College, Oscott, which he frequently visited and where he came to spend some time with the first Catholic Archbishop of Birmingham, William Bernard Ullathorne, who retired to Oscott. He and Cardinal Newman used to walk up and down the Beeswax corridor, praying and conversing together.

Newman preached his famous Second Spring sermon from the pulpit in Oscott. He also preached at St. Chad’s Cathedral, in the center of Birmingham.

So there are lots of tangible reminders of his legacy, but above all, I would say, the most significant part of the legacy is the continuing life of the Oratory community, the Oratory Fathers here in Birmingham, and then the foundations which they have laid in Oxford itself, which is a poignant reminder of his love for Oxford, and then beyond with other oratories.

My first impression of the cardinal’s rooms in the Birmingham Oratory was how modest they are. They are the same as everybody else’s rooms. I was also struck by how deeply personal the contents and appearance of the rooms are.

To preserve as much as possible, those rooms still don’t have any electric lighting. It’s natural light, but blinds, etc, are used in order not to let direct sunlight damage anything.

As you go into a principal room, you see it is lined with the books which were the most most intimate part of his reading, the things he wanted to be able to pull down off the shelves in his own rooms. His vast library is accessible and that’s different. The volumes that he amassed over the years are all intact.

When he became a cardinal, he had to be given an additional room as the bed chamber, and the area of his room behind the screen, where he would have slept, was converted into a small chapel, which again was requisite.

Cardinal Newman was permitted by the Holy Father, Pope Leo XIII, to continue to live in Birmingham. Those cardinals who were not diocesan bishops were required by custom, generally, to live in Rome. But he was dispensed from that, so he could continue living with the community.

Newman’s principal room at the Birmingham Oratory in England, with the altar screened off from his writing desk and books. © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

Newman’s principal room at the Birmingham Oratory in England, with the altar screened off from his writing desk and books. © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

But it meant that they changed his room, so that there was a tiny chapel there. When you go to the chapel, you realize you’re at the heart of the cardinal’s daily life, where he prayed and celebrated Mass. The chapel is surrounded by images of the saints — St. Francis de Sales being a very prominent image there. It was from St. Francis de Sales that he took his motto, Cor ad cor loquitor, Heart speaks unto heart.

Also, the wall is covered with photographs of friends and family, the people who were closest to him. You have a sense that when he was celebrating Mass, he was in the company of the saints and the angels, but also very close to people that he knew, the living and the faithful departed.

So there is a unique atmosphere in those rooms, and it’s a real privilege to be able to go from time to time and pray there. It doesn’t have the atmosphere of a museum at all. There’s a living sense of the presence of the saint in those rooms.

Images of Newman’s friends to the right of the altar in his room. © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

Images of Newman’s friends to the right of the altar in his room. © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

Because of the rooms’ fragile conditions, and the impact of humidity, and human presence, they do try to limit visits to the cardinal’s room considerably. Generally, they are not open to public view.

What they do have, however, in the Oratory is an exhibition of artifacts on the ground floor — and a very beautiful setting it is too. They’ve taken things from the cardinal’s rooms and displayed them, together with explanatory information.

Every two years, the Catholic bishops of England and Wales and the Anglican bishops of the Church of England and the Church in Wales have a regular meeting. There’s an element of prayer and pilgrimage, an element of joint witness, and an element of reflection, discussion, and study. We’ve had a number of these meetings over the years, encouraged originally by Pope Benedict.

In the context of a meeting in Norwich [in January 2024], we had a presentation and a discussion on St. John Henry Newman, as a saint who lived part of his life in the Church of England and part of his life in the Roman Catholic Church.

The Archbishop of Canterbury and the Archbishop of York [the Church of England’s senior leaders] approached Cardinal Vincent, because we’d shared with them information about different bishops’ conferences writing to the Holy See to support the request for the cardinal to be recognized as a Doctor of the Church. They asked if it would be possible for them to write to the Holy Father. The cardinal assisted them in that, and they wrote a joint letter to Pope Francis via the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints. The letter forms part of the positio, the official documentation which makes the case for requesting Newman’s recognition as a Doctor of the Church.

In the process of investigating the request, the Holy See, through the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints and the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, looks again at all the saint’s teachings and writings, and assesses them according to the criteria it has for a Doctor of the Church.

In this case, they included everything that Cardinal Newman wrote and taught as an Anglican. That’s the first 40 or so years of his life. In fact, Cardinal Newman himself agreed to and oversaw the republication of sermons and other writings from that period. So this was all part of the recognition of him as a Doctor of the Church.

It’s unusual and unique in that it will be the first time that teachings that were offered during his time as an Anglican were included with what he wrote and taught as a Catholic. So there is something for both our communions in this as well. It’s a really remarkable thing. It just emphasizes the contribution that St. John Henry Newman has made to Christian unity.

I think others have said this, but Cardinal Newman’s impact on the Anglican Communion — the Church of England, in particular, on its liturgy, theology, and ecclesiology — has been just as great as that within the Catholic Church universally.

Anglican clergy attend Newman’s canonization in St. Peter’s Square on Oct. 13, 2019. © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

Anglican clergy attend Newman’s canonization in St. Peter’s Square on Oct. 13, 2019. © Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk.

We’re waiting to see what is being planned by the Oratorians in Rome or universally. There’s likely to be some kind of celebration, I would think, in Rome, possibly at the Chiesa Nuova.

We will also be wanting here in the archdiocese — at the Birmingham Oratory, in all likelihood — to recognize the formal declaration.

We’re uniquely placed in England and Wales to recognize the ecumenical significance of this as well. It’s something which would be good to be able to plan alongside our ecumenical partners, and in particular with the Church of England.

There are also quite a number of celebrations happening more locally, because several schools have St. John Henry Newman as their patron. There’s one new parish dedicated to St. John Henry Newman in Wolverhampton, and they’ve got a round of festivities happening — social things, as well as the spiritual —in celebration of this.

I haven’t heard at all if there will be a specific title.

Recently, we have a wonderful festival hosted at St. Mary’s College, Oscott, called WeBelieve. One of the presentations was by Jacob Phillips from St. Mary’s University, Twickenham. He gave a brief presentation on Cardinal Newman and friendship, and the centrality of friendship to St. John Henry. In light of that, I was thinking something like Doctor Amicabilis would be very fitting.

In choosing his life as an Oratorian from the very outset, he wanted this to be his vocation within a community where friendship was very important. Tracing the element of friendship in St. John Henry Newman’s life indicates the significance again of his motto, Heart speaks unto heart.

You might have expected Newman, this great intellect, to have chosen “Mind speaks unto mind” as his motto. But he saw the communication was deeper than the intellectual and that it entails the whole person. Friendship is a really important theme in his life.

A painting of Bl. Dominic Barberi in the Passionist archives in Rome. Public Domain.

A painting of Bl. Dominic Barberi in the Passionist archives in Rome. Public Domain.

I do, yes. For the last 40 years, I’ve prayed every day for the canonization of Bl. Dominic. After studying in Rome, I went with my parents to his shrine at St. Helens in Lancashire and got to know him then. When I was appointed to Birmingham, it was an opportunity for me to do a little more in promoting the cause.

St. John Henry wanted Bl. Dominic to receive him into the Catholic Church. He recognized in him this holiness of life, which was ultimately what converted Newman, I think. Intellectually, he was attuned already and convinced, but I think needed some display of holiness of life. I’m not saying he didn’t see it in others, but he certainly recognized it in Bl. Dominic.

We ask people to pray again for the miracle that’s needed for Bl. Dominic, more than 60 years since his beatification [by Pope Paul VI in 1963]. I think it would be a source of great joy to St. John Henry Newman to see this recognition for the humble Passionist priest who received him.