The death of a national icon often raises difficult legal and customary questions about who is entitled to their property and who has the right to decide their burial arrangements.

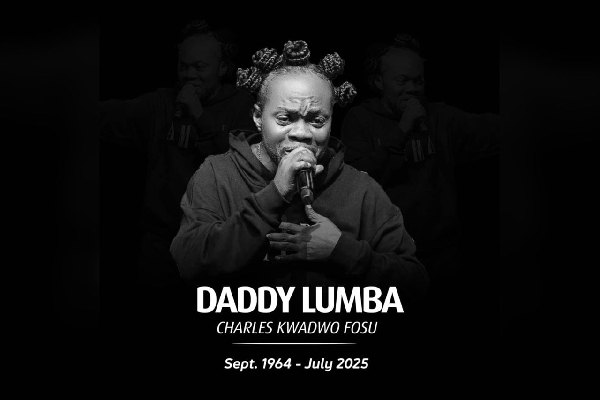

The recent passing of the celebrated Ghanaian musician, Daddy Lumba, has evoked popular discourse on how these issues could play out between a nuclear family—the spouse (s) and children—and the extended family, within the framework of Ghanaian law.

If the deceased legend left a valid will in accordance with the Wills Act, 1971 (Act 360), then the terms of that document controls how the estate is distributed. This would include economic rights such as royalties, intellectual property, and real or personal property. A will can also direct burial arrangements, and Ghanaian courts will generally respect those written wishes, provided the will is valid.

If the deceased died intestate (without a will), the Intestate Succession Law, 1985 (PNDC Law 111) applies to self-acquired property:

The spouse and children receive the first share of the estate.

The parents (unfortunately deceased) would have been entitled to a statutory

portion.

Only what remains after these shares are distributed passes to the extended family under customary law.

Where the parents have predeceased the deceased, and in this case they have, the

extended family’s share is smaller and may only consist of residual property after the nuclear family’s entitlements are satisfied.

In the absence of a valid will or other legally binding direction regarding the

disposition of one’s remains, the issue of burial in Ghana is generally determined in accordance with applicable customary law. Under most Ghanaian customary systems, the right rests primarily with the Abusua—the deceased’s traditional family—rather than the nuclear family. The Abusua, acting through its recognised head (often the Abusuapanyin), customarily decides both the location and manner of burial, taking into account the family’s traditions, lineage, and ancestral grounds.

Accordingly, if the Abusua resolves that the burial should take place at a specific location—such as Nsuta—that decision will ordinarily be binding and will prevail over the wishes of other parties, including the spouse and children, unless it can be shown to contravene statutory law, constitutional rights, or other overriding legal principles. Any challenge to such a decision would need to be mounted in a competent court, supported by evidence that the customary position should yield to legal provisions, testamentary directions, or equitable considerations.

That said, courts have in some cases considered equitable factors—such as the

deceased’s known wishes and the views of the spouse and children—when resolving disputes about burial. Still, without a will, customary law remains the default position.

Whether the deceased dies with or without a will, the estate must be formally

administered through the courts. This is done via a grant of probate (for a will) or letters of administration (for intestacy). While family meetings may occur early in the process, only the court’s grant gives legal authority to manage and distribute the estate. In celebrity cases, public image and family dignity may influence out- of-court settlements to avoid adverse media spectacle

The fact that the deceased had strained or no personal contact with the extended

family does not nullify their customary role. Even where relations were strained, customary authority over burial is deeply entrenched. However, the nuclear family (spouse and children) may apply to court for injunctive relief or burial orders if they can show:

The extended family’s decision is unreasonable.

It violates the dignity or wishes of the deceased.

It causes undue hardship or conflict contrary to public interest.

In my two decades of legal practice, I find that a clear, well-drafted will an

effective arsenal in preventing disputes after a person’s death. In my experience, wills resolve as much as 85% of potential conflicts that typically arise among family members, beneficiaries, or interested parties.

A properly executed will provides legal certainty, affirms the testator’s intentions, and reduces ambiguity over the distribution of property, appointment of executors, and burial wishes. It empowers the surviving family to focus on mourning and remembrance rather than legal contention.

Conversely, a poorly drafted, vague, or incomplete will can sow confusion and

become a fertile ground for disagreement and litigation. Ambiguities in language, omissions of key assets or beneficiaries, or failure to comply with formal legal requirements can result in protracted disputes that fracture families and consume estates in legal costs.

In some instances, such poorly constructed wills are challenged in court and either invalidated or interpreted in ways that distort the original intent of the deceased. In short, while a good will brings peace, a flawed one can leave behind a legacy of conflict.

Engaging a skilled estates lawyer to prepare or review your will is not only wise but essential. The technical requirements for a valid will under Ghanaian law are strict, and even minor errors in wording, execution, or witnessing can render an otherwise well-intentioned document ineffective.

An experienced lawyer ensures that your will is drafted in clear, unambiguous language, complies with all statutory formalities, and fully reflects your intentions for the distribution of your estate and the handling of your final wishes.

As our elders say, “The prudent person learns from the tribulations of others.” The passing of a public figure often casts a spotlight on how quickly the period of grief can give way to disputes over property, burial rights, and legacy. Family harmony can be shattered, reputations tarnished, and estates diminished by legal battles that could have been avoided. A valid, well-drafted will remains a useful safeguard against such conflicts, providing certainty, preserving dignity, and ensuring that the focus after death remains on honoring the life lived rather than contesting its aftermath.