If humans ever travel to another star, the journey is likely to take many lifetimes. Generations will live and die without ever setting foot on a planet, knowing only the spacecraft on which they were born.

A global competition has revealed what those vast, self-contained environments might look like — complete with fusion engines, artificial gravity and social systems designed to keep the peace during a centuries-long trip.

The Project Hyperion design competition, launched last year, invited teams of scientists, engineers, architects and social theorists to develop detailed plans for a “generation ship”, a self-sustaining vessel capable of carrying about 1,000 people on a one-way, 250-year journey.

Entries could only use existing technologies or those deemed to have a plausible chance of emerging in the near-ish future, which included nuclear fusion, the power source that fuels the sun.

Faster-than-light travel was not allowed. Nor were systems that would hold the crew in states of suspended animation. Instead, these vessels would be built for a drawn-out trundle through the void.

Nearly 100 submissions were judged by an expert panel that included Nasa scientists. They assessed not only engines and hulls, but also the chances of a ship’s inhabitants tearing each other apart.

Designers imagined what the best materials and fit for clothing on board an interstellar ship would be

The winner was Chrysalis, a 58 km-long cylinder that looks rather like a highlighter pen abandoned by a celestial schoolchild. Much of the structure is a massive fuel tank containing helium-3 and deuterium. These would feed a direct fusion drive — a yet-to-be-invented propulsion system that would draw power from a controlled fusion reaction.

Tucked inside would be a series of concentric cylinders, which would rotate to generate artificial gravity. The inner walls would host the living quarters, farms and community infrastructure needed to sustain life.

The judges commended the meticulous detail of the plans, which included an explanation of how its inhabitants would be psychologically screened via a decades-long vetting process spent living in isolated Antarctic bases.

On board, they would live in a so-called “sociocracy”, a way of running groups where everyone’s voice is heard, decisions are made by agreement rather than voting and people organise themselves into small, connected teams that work together. Each inhabitant would be allowed to have children, not necessarily with the same partners, to keep the population stable.

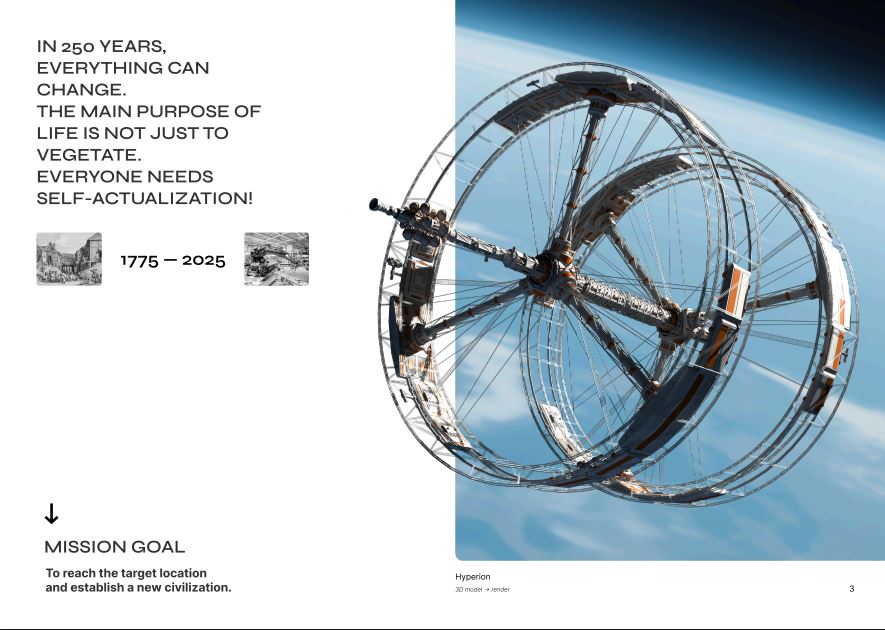

Second place was given to WFP Extreme, which resembles two 500m-wide ferris wheels joined together.

The WFP Extreme was praised by judges for its particularly strong focus on cultural and societal dimensions

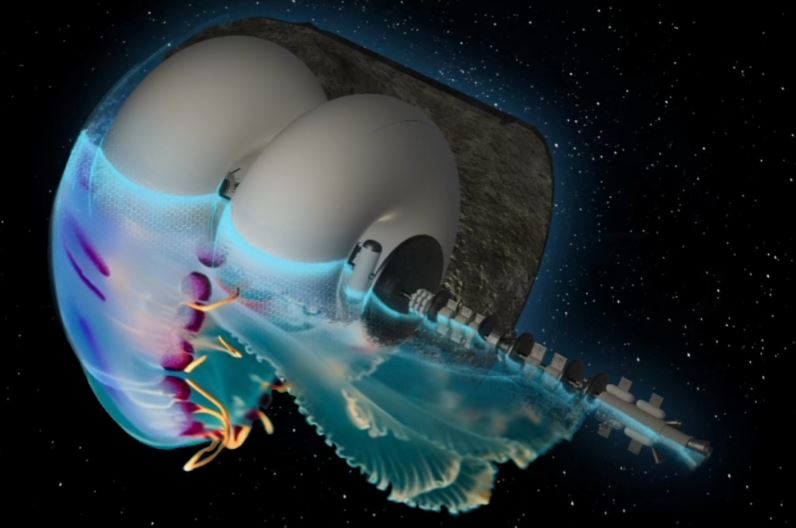

In third place was Systema Stellare Proximum. This design again has sections that would rotate to generate gravity. These would be embedded inside a hollowed-out asteroid. Shaped to look like a jellyfish, the rock would protect the inhabitants from the dangerous radiation that pulses through space.

Systema Stellare Proximum has an especially “sci-fi” appearance

The question remains, though, whether 250 years would be enough time to get anywhere interesting. The nearest star system to Earth, Alpha Centauri, lies just over four light years away, about 40 trillion kilometres. To put that in perspective, if a spacecraft were to travel at the speed of the Apollo missions to the moon, it would take nearly 118,000 years to arrive –— longer than our species has been in Europe. For Voyager 1, our most distant spacecraft, it would take nearly 80,000 years. For now, travelling such vast distances remains firmly in the realm of science fiction.

Even so, Dr Andreas Hein, executive director of the Initiative for Interstellar Studies, which ran the competition, described the ideas as valuable. The contest was “part of a larger exercise to explore if humanity can travel to the stars one day,” he said.

“It envisions how a civilisation might live, learn, and evolve in a highly resource-constrained environment and may also provide valuable insights into our future on Earth.”