A new chapter in UK–India relations began when on July 24, 2025, Prime Ministers Narendra Modi and Keir Starmer signed the long-awaited Free Trade Agreement (FTA) — a bold, sweeping accord that transcends tariffs and quotas, aiming to reshape global trade flows between the world’s fifth and sixth largest economies. Hailed as “the most economically significant agreement for Britain since Brexit,” the deal opens wide channels of commerce, talent, and innovation between two countries with intertwined colonial histories and increasingly complementary economic trajectories.

Jonathan Reynolds, UK business and trade secretary and Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister. (Bloomberg)

Jonathan Reynolds, UK business and trade secretary and Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister. (Bloomberg)

Negotiated over 13 formal rounds spanning three years, the FTA spans five critical domains: goods, services, investment, professional mobility, and social security cooperation.

- Goods: India will phase out tariffs on 90% of UK exports — including iconic products like Scotch whisky, luxury cars, cosmetics, and medical devices. Whisky duties drop from 150% to 75% immediately, reducing further to 40% over the next decade. UK cars, once taxed at over 100%, now gain quota-based access at just 10%.

- Indian exports: UK will grant 99% duty-free access to Indian products, favouring textiles, gems and jewellery, auto components, seafood, and agricultural goods — a crucial win for India’s labour-intensive sectors.

- Services and mobility: The UK has opened up 137 service sub-sectors, including private health care, education, finance, and IT services. An annual mobility quota allows 1,800 Indian professionals (from chefs to coders) to work in the UK with fast-tracked visa approvals and mutual qualification recognition.

- Social security agreement: Under the Double Contribution Convention, Indian professionals on short-term assignments (up to 3 years) will be exempt from UK social security payments, saving Indian companies and workers an estimated ₹4,000 crore annually.

- Government procurement: UK firms gain access to India’s ₹4.09 lakh crore procurement markets, while Indian businesses can bid on £38 billion worth of UK government tenders.

Both nations stand to benefit significantly:

- For the UK, a much-needed post-Brexit economic anchor, connecting British firms with India’s booming consumer base.

- Helps diversify away from Eurozone dependence and align with Indo-Pacific supply chains.

- Sectors such as alcohol, automotive, pharmaceuticals, and aerospace (e.g., Rolls-Royce and Airbus contracts with India) are poised for growth.

- Estimated annual GDP boost of £4.8 billion and £6 billion in new investments, creating 2,200+ jobs.

- For India, this enables duty-free market access across sectors historically stifled by high UK tariffs.

- Boost for MSMEs and labour-intensive exports.

- Supports internationalisation of Indian services, especially in education, fintech, and IT.

- Expected to attract strategic investment in clean energy, AI, semiconductors, and advanced manufacturing.

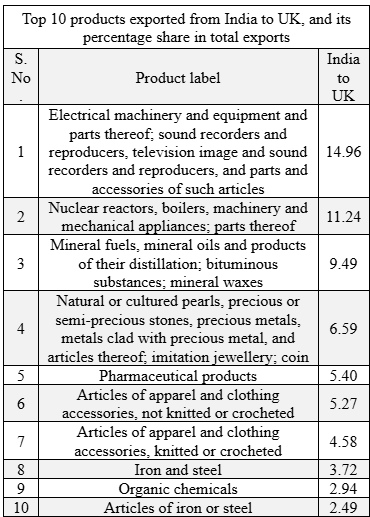

Source: https://www.trademap.org/

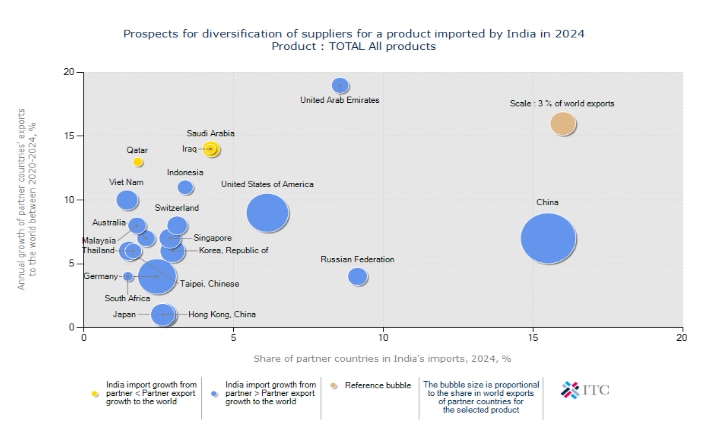

Source: https://www.trademap.org/  Imports: India’s major import partners are mentioned and the size of the bubble shows the share in imports. (https://www.trademap.org/)

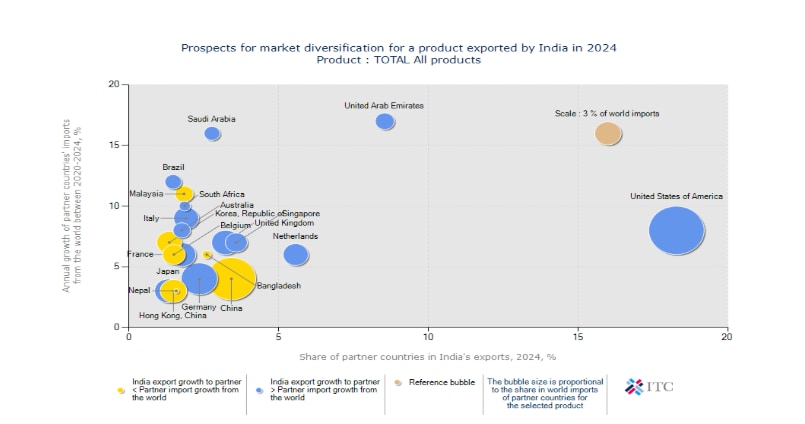

Imports: India’s major import partners are mentioned and the size of the bubble shows the share in imports. (https://www.trademap.org/)  Figure shows major export partners’ and size of the bubble shows the share of exports (https://www.trademap.org/ )

Figure shows major export partners’ and size of the bubble shows the share of exports (https://www.trademap.org/ )

It is clear that India exports a considerable amount of goods and services to the UK, and maintains a hefty trade surplus. However, this FTA will open the Indian market for the UK, and time will tell how it will unfold for both the nations.

Currently, India enjoys a trade surplus with the UK, exporting over $40 billion annually and importing around $20 billion. The new agreement could widen this gap — especially with enhanced access for Indian manufacturers and service providers.

However, trade economists caution that while the surplus may grow in the short-term, UK exports (particularly in premium goods and services) could gain momentum, especially with lower entry costs and stronger brand positioning. The net effect depends on how agile Indian exporters are in scaling production and navigating compliance frameworks.

There’s also talk of trade inversion risks — if cheaper UK imports undercut Indian domestic players. For instance, British lamb and salmon may pressure Indian meat producers. Likewise, cosmetics and processed food products could disrupt small-scale Indian FMCG markets. To address this, India has included safeguard mechanisms and phased liberalisation timelines in sensitive sectors.

India’s expectations hinge on four interlinked trajectories:

- Export competitiveness: With duty-free access, sectors like textiles, gems, auto components, and pharma could see double-digit growth. Ramping up quality standards and supply chains will be key.

- Skill recognition and diaspora mobility: For India’s global workforce, especially in health care and education, the FTA promises smoother professional mobility and recognition of credentials, strengthening India’s soft power globally.

- Innovation and investment: India expects a surge in UK FDI — especially in green hydrogen, quantum computing, and EVs — giving a fillip to its Make in India and Startup India initiatives.

- Strategic standing: As India deepens ties with the UK, it simultaneously asserts its growing stature in global trade leadership. Coupled with FTAs already signed with Australia and the UAE, India’s position as a hub for diversified, defensible global trade becomes more pronounced.

A joint review body will assess the agreement annually, with provisions for amendment, fast-track dispute resolution, and dynamic quota adjustments. Both governments have committed to transparency and consultation, especially on contentious sectors.

Critics argue the real test lies not in signatures but implementation. Policy clarity, exporter handholding, compliance simplification, and SME support systems will determine whether this ambitious pact meets its lofty promise.

As a new trade corridor emerges between London and Delhi, the agreement offers a powerful reminder that while geopolitics may divide, trade — done right — can unite economies and uplift livelihoods.

This article is authored by Narinder Kumar, assistant professor, School of Economics and Public Policy, RV University.