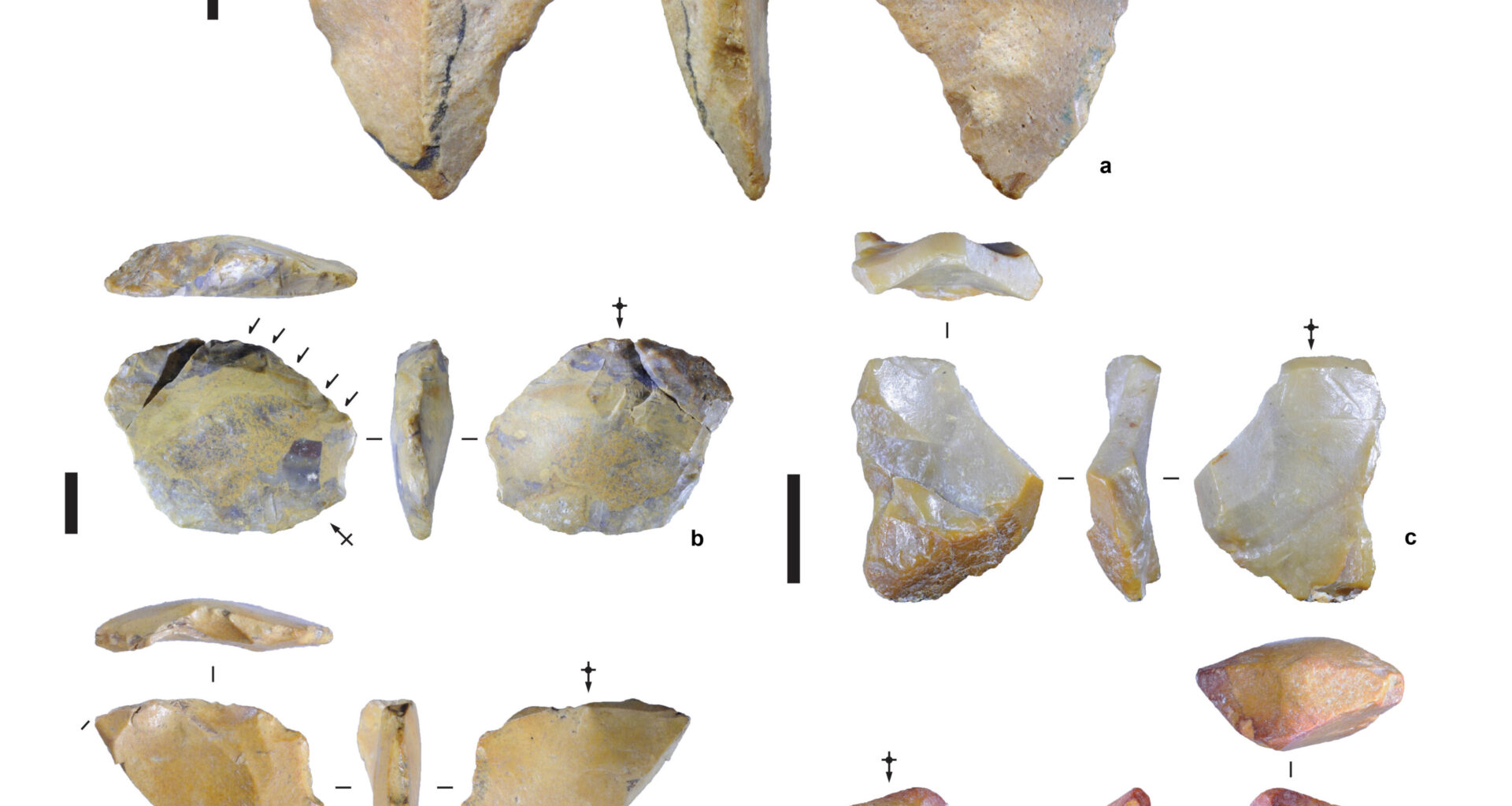

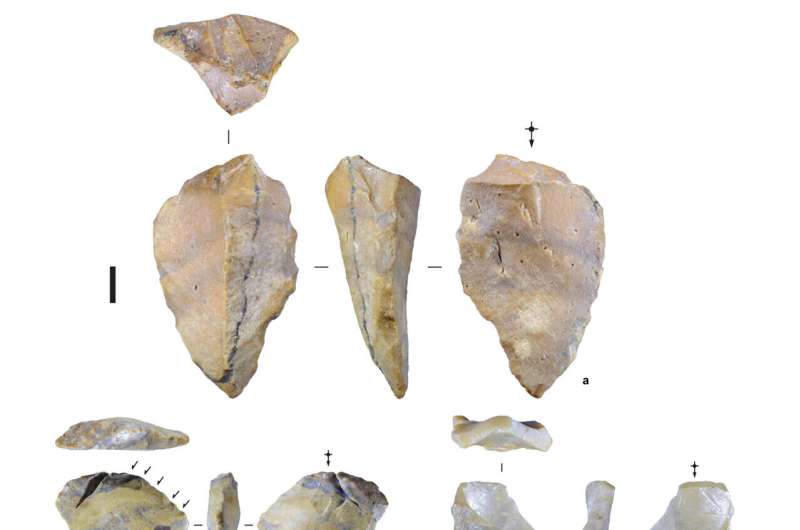

Stone tools were excavated from Calio, Sulawesi, and dated to over 1.04 million years ago. The scale bars are 10 mm. Credit: M.W. Moore/University of New England

Findings made by Griffith University researchers show that early hominins made a major deep-sea crossing to reach the Indonesian island of Sulawesi much earlier than previously established, based on the discovery of stone tools dating to at least 1.04 million years ago at the Early Pleistocene (or “Ice Age”) site of Calio.

Budianto Hakim from the National Research and Innovation Agency of Indonesia (BRIN) and Professor Adam Brumm from the Australian Research Center for Human Evolution at Griffith University led the study, “Hominins on Sulawesi during the Early Pleistocene,” published in Nature.

A field team led by Hakim excavated a total of seven stone artifacts from the sedimentary layers of a sandstone outcrop in a modern corn field at the southern Sulawesi location.

In the Early Pleistocene, this would have been the site of hominin tool-making and other activities such as hunting, in the vicinity of a river channel.

The Calio artifacts consist of small, sharp-edged fragments of stones (flakes) that the early human tool-makers struck from larger pebbles that had most likely been obtained from nearby riverbeds.

The Griffith-led team used paleomagnetic dating of the sandstone itself and direct-dating of an excavated pig fossil, to confirm an age of at least 1.04 million years for the artifacts.

Previously, Professor Brumm’s team had revealed evidence for hominin occupation in this archipelago, known as Wallacea, from at least 1.02 million years ago, based on the presence of stone tools at Wolo Sege on the island of Flores, and by around 194 thousand years ago at Talepu on Sulawesi.

Stone tools from Calio, Sulawesi. Credit: M W Moore

The island of Luzon in the Philippines, to the north of Wallacea, had also yielded evidence of hominins from around 700,000 years ago.

“This discovery adds to our understanding of the movement of extinct humans across the Wallace Line, a transitional zone beyond which unique and often quite peculiar animal species evolved in isolation,” Professor Brumm said.

“It’s a significant piece of the puzzle, but the Calio site has yet to yield any hominin fossils; so while we now know there were tool-makers on Sulawesi a million years ago, their identity remains a mystery.”

The original discovery of Homo floresiensis (the “hobbit”) and subsequent 700,000-year-old fossils of a similar small-bodied hominin on Flores, also led by Professor Brumm’s team, suggested that it could have been Homo erectus that breached the formidable marine barrier between mainland Southeast Asia to inhabit this small Wallacean island, and, over hundreds of thousands of years, underwent island dwarfism.

Professor Brumm said his team’s recent find on Sulawesi has led him to wonder what might have happened to Homo erectus on an island more than 12 times the size of Flores.

“Sulawesi is a wild card—it’s like a mini-continent in itself,” he said.

“If hominins were cut off on this huge and ecologically rich island for a million years, would they have undergone the same evolutionary changes as the Flores hobbits? Or would something totally different have happened?”

More information:

Hominins on Sulawesi during the Early Pleistocene, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09348-6 , www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09348-6

Provided by

Griffith University

Citation:

Archaeologists find oldest evidence of humans on ‘Hobbit’s’ island neighbor—who they were remains a mystery (2025, August 6)

retrieved 7 August 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-08-archaeologists-oldest-evidence-humans-hobbit.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.