BERLIN – Germany’s new coordinator for relations with Poland, Knut Abraham, had been in office for just three days when his job got a lot harder.

On the night of 1 June, the Christian Democrat MP stayed up late listening to radio coverage of Poland’s presidential election until he unwittingly fell asleep.

Exit polls projected a narrow victory for Rafał Trzaskowski, backed by centrist Prime Minister Donald Tusk, an ally of German Chancellor Friedrich Merz. But when Abraham woke up, the final count confirmed the far-right nominee, Karol Nawrocki, as the winner.

Abraham’s first thought was: “This will be a challenge, for the German-Polish relations as well.”

It’s him who has to confront it. As coordinator, Abraham will support one of Merz’s core European policy goals: repairing a relationship that is both essential for Europe’s security architecture and deeply fraught.

Abraham says his government has ideas on how to get there. And nothing, it seems, is off the table.

History still hurts

Germany and Poland are not only the largest economies on either side of the EU’s east-west divide; they are also two of Europe’s top military spenders and key backers of Ukraine against Russia’s invasion.

Yet the Nazi occupation of Poland, which claimed over five million Polish lives, remains an open wound. Germany’s refusal to pay reparations is routinely weaponised by Poland’s nationalist Law and Order party (PiS), which backed Nawrocki. Being too lenient towards Berlin can thus be a political risk in Polish politics.

This week, the Polish foreign office fired Abraham’s Polish counterpart and scrapped the position altogether over rumours that the incumbent had proposed a seminar on returning cultural objects left behind by expelled Germans in 1945.

Merz has vowed to be “empathetic towards our eventful history” and “end the speechlessness between Berlin and Warsaw,” which he blamed on the preceding government.

But his own decision to close Germany’s border to asylum-seekers once in office fuelled the flames and handed new talking points to Poland’s far right.

Germany’s move to block entry to irregular migrants led to the spread of false rumours that German police were systematically pushing asylum-seekers into Poland.

In response, Poland has instated checks of its own, capping a botched start for Merz’s German-Polish reset.

The price to pay

Abraham, who served as an envoy at the German embassy in Warsaw for three years, admitted that the border issue is proving a major burden for the relationship.

But he insists that the temporary checks also “signal a change in Germany’s migration policy that aligns more closely with Poland’s position,” he said, adding that he “encountered a lot of understanding” from Polish officials.

That is the key priority for him: “The most important thing is to restore trust,” Abraham said, adding that the new government was “already integrating Poland at a level of intensity that the previous government did not demonstrate”.

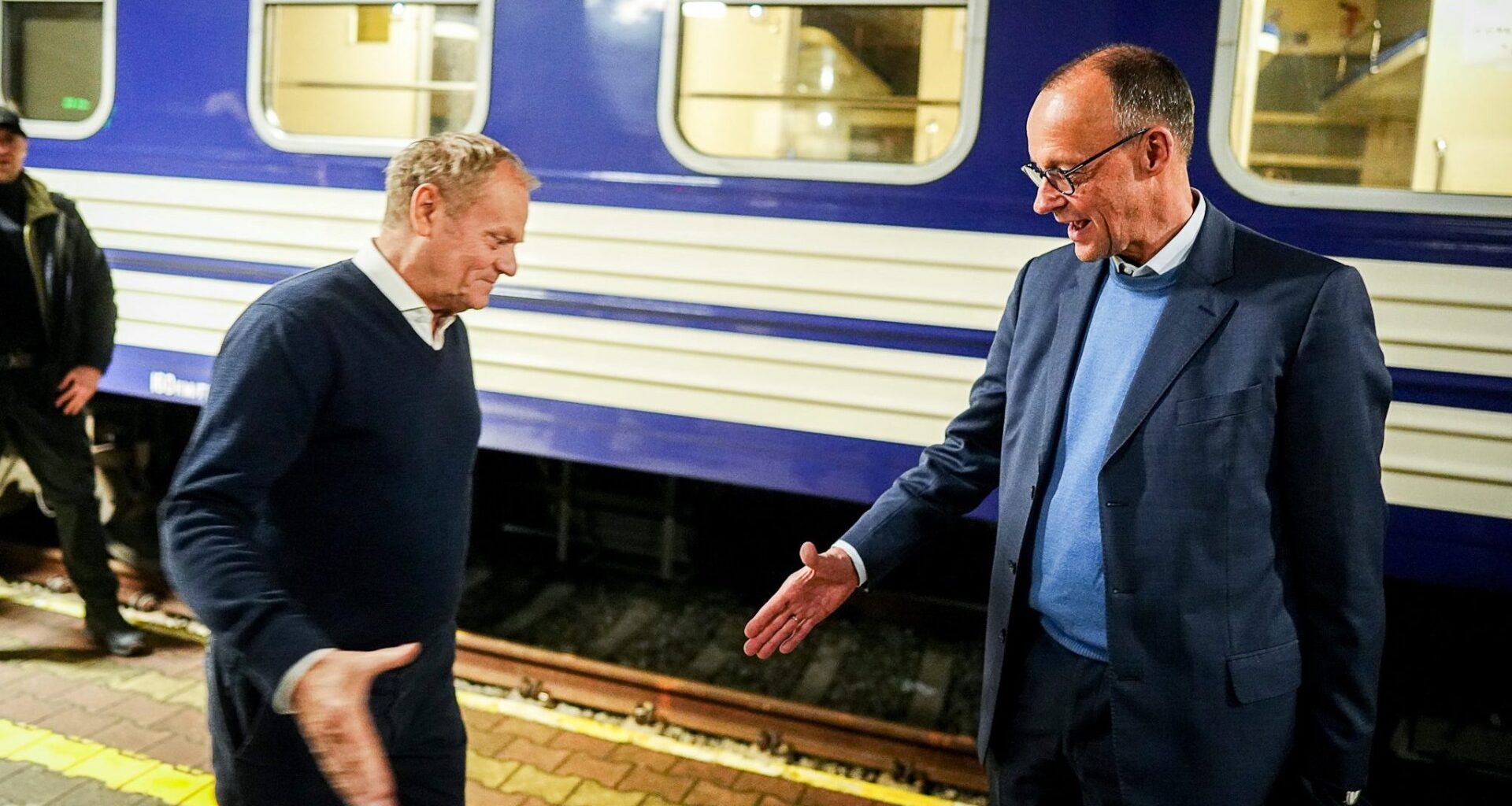

Merz notably became the first chancellor to visit Warsaw on his first day in office, and took a trip with Tusk and the leaders of France and Britain to Kyiv three days later. A joint cabinet meeting is being prepared for this year, and the signing of a bilateral friendship treaty in 2026 is on the table.

But more importantly, Abraham says that the government has resumed negotiations over a goodwill package that Merz’s predecessor, Olaf Scholz, had been working on before they collapsed last year over withholding funding. The package also included investments in Poland’s security.

Warsaw took that “as an affront and proof of German disinterest”, he said, adding that the Germans ultimately failed “to develop genuine joint initiatives based on Polish priorities, including security, external border protection, and cyber security.”

According to Abraham, the government is also taking seriously the Polish desire to get Germany’s support on security matters.

Warsaw shares 1,310 kilometres of border with Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, protected by a military bulwark, the so-called East Shield.

But Germany first consistently underestimated the threat from Russia, then Scholz’s government blocked Polish initiatives for joint EU funding for Europe’s eastern flank, to Warsaw’s dismay.

It is no longer off limits: Abraham said that Germany “should be very receptive” if Poland asked for financial support to beef up its Eastern frontier.

PiS and pragmatism

The election of a PiS-backed president, who was inaugurated on Wednesday, has complicated Berlin’s plans, however.

His victory means that Tusk’s policy agenda will mostly be blocked by a hostile president ahead of the 2027 national elections.

Abraham notes that this has all but kicked off the Polish campaign, with Tusk now forced to focus on messaging, which includes being cautious about cooperating with Berlin. After all, Nawrocki has previously railed against Germany, while Tusk has also faced personal smear campaigns over his grandfather’s forced service in the German Wehrmacht.

But the German coordinator tries to be pragmatic: Nawrocki’s victory won’t change anything substantive about the relationship, he said, adding that Nawrocki’s predecessor was also PiS-backed and had stood by Poland’s EU membership, NATO integration, and support for Ukraine.

Germany won’t be able to “expect applause at all times” for his offers of cooperation, he said.

But if they “reflect a clear desire for friendship and partnership … I’m positive that they will elicit the right resonance in the Polish debate”.

(mm)