“Do you think there might be a play to be written about the battle for No 1 between Blur and Oasis back in August 1995?”

This was the question posed to me on the phone by the theatre producer Simon Friend in the early spring of 2023. And honestly? I really didn’t think so. I wondered if what Simon (a very successful commercial theatre producer: The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, Life of Pi) was after was a sort of

“Britpop! The Musical”. Chorus lines high-kicking and chirruping “PARKLIFE!” while some fraught but ultimately joyous love story played out front of stage. (She was a Blur fan. He was Team Oasis, but their love crossed all divides, and so forth.)

So I was of a mind to say no. And then I thought about it a little more and it occurred to me that perhaps there was a funny play lurking in the idea. A kind of David Mamet piece: men screaming at each other in hot rooms about something that, when we pulled the camera back, was ultimately ridiculous. The comedy, it seemed to me, would come from taking an elephant gun to an ant, from investing the idea of releasing two pop records on the same day with the kind of stakes normally

reserved for a drama about the Cuban missile crisis, or the D-Day invasion.

Blur in 1995

LOCAL WORLD/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

A quick sidebar for those of you who can’t recall — or who are much under 40 — 30 years ago this week, on August 14, 1995, Blur and Oasis released singles on the same day, Country House for the former and Roll with It for the latter. One of them was bound to be No 1. It’s something of a cosmic joke that both were among the weakest songs in either band’s repertoire, with Country House probably having the edge musically. (The Oasis singer Liam Gallagher has since claimed a fondness for Roll with It, and the fact that it features in the reformed Oasis set list is either a sop to him or a giant two fingers to history. Or both.)

As the media frenziedly pointed out, Blur were art school, southern and middle class, while Oasis were dole queue, northern and working class. It was a story handcrafted to punch all of Britain’s buttons and it took both groups from the pages of the music press to the front covers of the tabloids. Spoiler alert: in the end Blur won the battle for No 1, selling 274,000 singles to Oasis’s 216,000. (Big numbers for the time, and unthinkable today when the Top Ten singles chart would struggle to get half a million sales combined.) However, by the end of the year Oasis had very much won the war, with (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? shifting 200,000 copies a week as it went on its merry way to becoming the biggest-selling British album of the decade. A year on from the chart battle, they played two nights at Knebworth to 250,000 people (tickets cost £22.50).

Both singles were among the weakest songs in either band’s repertoire

Anyway, I rang Simon back and pitched him my David-Mamet-men-shouting idea. “Go to it,” he said. We made a deal and off I went, back 30 years, back an entire generation.

Back to 1995.

God it was hot that summer, the summer I moved to Notting Hill Gate. The hottest since 1976. I was sharing a maisonette on Westbourne Park Road with my friend John (now there’s a line that could have come straight from the pen of Joe Orton) and I had just been made product manager at London Records. John was head of business affairs at Go! Discs.

• Blur, Pulp, Oasis or Suede: who is the best Britpop band?

We had Goldie, East 17 and Bananarama. Go! had Paul Weller, Portishead and the Beautiful South. I was 27, living in west London and I had finally started making more than my age in money. (This used to be a thing, kids.) And £30,000 a year felt like an awful lot of cash in 1995. And indeed it was, being more like an £80,000 or £90,000 salary today. My rent was £400 a month. (Again, this used to be a thing, kids.) I had an expense account. In the mornings, John and I would race our company cars along the Westway to Hammersmith where our offices were. So yes, bliss was it in that dawn, etc, but to be young and in the music industry in W11 …

I’d spent the end of the 1980s in a very different London, living in Leytonstone for 18 months and playing guitar in an indie rock band. Back then the worlds of pub back rooms and the charts were two separate oceans. Well, one was an ocean. The other was a filthy pond. Sightings of major label A&R men in places like the Camden Falcon were as rare as Top 40 appearances by bands from our circuit. As the 1990s began I finally threw in the towel on being in a stupid bloody guitar band and went back to university to finish my degree.

What timing.

Over the next few years things began to change. First the House of Love and then, more dramatically, the Stone Roses changed the idea of how many records an indie guitar group could sell. And then came Suede. And then Blur. And then, finally, we got to the fullest expression of the changing

times.

• Blur’s Damon Albarn: ‘Britpop was nothing to do with me’

I first heard Oasis at a house party towards the end of 1993, when my friend and fellow 1980s indie band survivor Martin Kelly of Heavenly Records played me the demo of Live Forever. He was thinking of booking Oasis to support Heavenly act Saint Etienne on their upcoming tour. It was a searing moment. Those odd, diddling tom-toms and then it was the first time I’d ever heard that voice as it sang “Maybe, I don’t really wanna know …” I stood there, transfixed at first and then blown away as the song kicked in properly and suddenly Martin was clamping an arm around my shoulder and screaming in my ear — “EVERYTHING WE WANTED TO BE AND WEREN’T.”

Liam and Noel Gallagher in 1994

KEVIN CUMMINS/GETTY IMAGES

God, he got that right. Many of the elements on the record were straight from the demi-monde Martin and I came from: acoustic guitars and vintage amplifiers. And yet it was suffused with things light years beyond anything we’d ever been close to. The voice. The aching, yearning melody. In the years that were to follow I would prove myself a truly dismal music industry executive (the Coldplay and Muse demos both getting pegged straight in the bin) but, standing there speechless in a basement flat on Ladbroke Grove, I got one thing very right. “This lot,” I screamed back into Martin’s ear, “are going to be f***ing massive.”

As 1994 unfurled, so it proved. And it felt great. It always feels great as outsiders start to win. As the kind of music that you’d loved for years started to become dominant on the radio, in the charts, in the culture. As that decade of Bryan Adams or Wet Wet Wet or whoever being No 1 suddenly got put on notice.

• Girls and boys: why Britpop wasn’t as fun for the women

I worked on the outline of the play through the summer of 2023, I reread old diaries and all the books, everything from the sublime (John Harris’s peerless The Last Party) to the ridiculous (former Oasis tour manager Ian Robertson’s memoir Oasis: What’s the Story?). Gradually a shape to the thing began to emerge.

You had the Blur singer Damon Albarn at the Brit awards in February 1995, holding up his record-breaking fourth statuette of the night, the award for best British group, and saying, “This should have been shared with Oasis”, with the guitarist Graham Coxon behind him adding “much love and respect to them”. Then, later that same night, you had Noel Gallagher giving an interview where he said: “As far as I’m concerned it’s us and Blur against the world now.”

Blur at the Brit awards in 1995

SHUTTERSTOCK

By August that year you had Noel talking about Albarn and the Blur bass player Alex James and saying: “I hope them two get Aids and die.” Really? From “us against the world” to “get Aids and die” in six short months?

This, my friends, was what we call a “clear dramatic arc”. I had a draft written by the end of the year. As I was working, Blur reformed and played two nights at Wembley Stadium and I remember thinking, “Fantastic! There might just be an appetite for this thing.” As 2024 unfolded I did the usual thing of rewriting and redrafting while Simon went about his producerly business of finding a director (Matthew Dunster), a theatre and a cast. And then, that August, Oasis announced their reformation. And 14 million people tried to buy tickets.

• Read more music reviews, interviews and guides on what to listen to next

Or about 20 per cent of the UK population.

Oasis, it transpired, could have played Wembley Stadium for a month without touching the sides. And I thought back to that basement flat in the winter of 1993. This lot could be big.

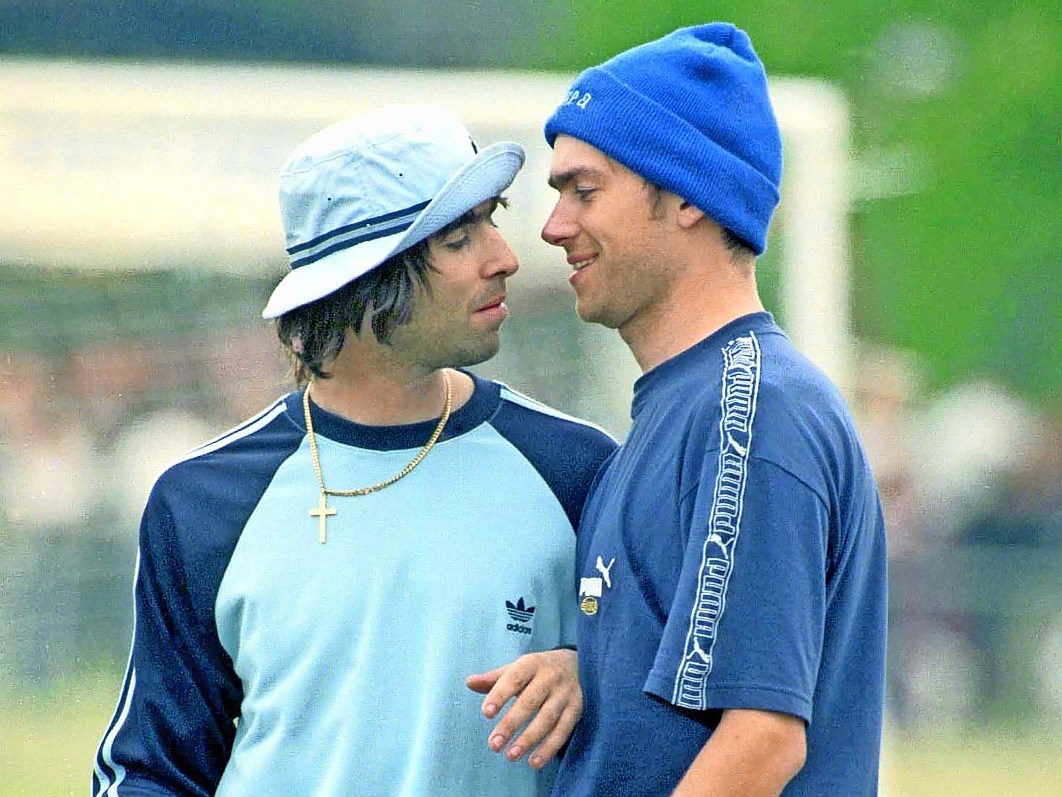

Liam Gallagher and Damon Albarn at a charity football match in 1996

MIRRORPIX

You try and tell the universal through the specific. The Battle came to be a tale of youth and bravado. Of ambition and — as the character Damon puts it in the play — “thinking with the blood”. Of boys in their twenties making decisions way above their pay grade and damn the consequences. It became about something else too, something I thought we’d lost along the way. In a time when a family of five often means five people watching five different programmes on five devices in five rooms, it became a celebration of how two pop groups releasing records could dominate the national consciousness, all the way from the NME to The Times to the News at Ten. The Blur/Oasis battle for No 1 didn’t divide the country — it united it. In a way I doubted we’d ever see again.

Until those 14 million ticket applications. Until this summer, when two brothers stepped on stage together one last time and we heard the whole country — from Cardiff to Edinburgh, from London to Manchester — sing as one.

The Battle by John Niven opens at Birmingham Rep on Feb 11, 2026