They went on an adventure, with a two-year contract as domestic workers. After that time, they were free to return. But they weren’t able to travel back from Australia for decades. Firstly, because the return ticket cost the equivalent of several years of work. Secondly, because the loneliness was so intense for them that many quickly accepted — with varying degrees of conviction and fortune — marriage proposals from men who had arrived a few years earlier. In Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Brisbane, they ended up settling down, becoming socially involved, starting families, and founding their own meeting places to combat homesickness and rootlessness. Huge Spanish social clubs were opened in several cities, even Basque pelota courts and gure txokos (social clubs), and later Galician cultural centers, and there were parties with paella and sangria, soccer tournaments, and even religious pilgrimages to pay homage to Our Lady of El Rocío in the middle of Oceania. For six decades, Spanish women have continued to meet on Saturdays in Sydney’s Centennial Park.

Inauguration of the Gure Txoko pelota court in Sydney (1967), in a photo preserved by the family of María Begoña Zubiaur and Francisco Javier Montero, who worked on the construction of the Opera House.Archivo Montero Zubiaur

Inauguration of the Gure Txoko pelota court in Sydney (1967), in a photo preserved by the family of María Begoña Zubiaur and Francisco Javier Montero, who worked on the construction of the Opera House.Archivo Montero Zubiaur

It all began in the early 1960s and could serve as the inspiration for a long television series. These were young women recruited from villages in northern Spain: the Basque Country, Navarre, Asturias, Cantabria, Galicia, and only later from regions further south. They were drawn in by Catholic institutions under Franco’s regime in what was dubbed “Plan Marta.” They arrived in Australia in the footsteps of a contingent of men, also mostly from the Basque Country and Cantabria, who had been recruited through “Operation Kangaroo” (1958-1963) to provide cheap, reliable labor for the plantations, especially those growing sugar cane. These women were known as the “martas” or “marthas,” and they were called upon to become perfect domestic servants, like the biblical figure Martha of Bethany or the class described by Margaret Atwood in The Handmaid’s Tale. Both men and women breathed life into and worked to build a country that was, for the most part, still in serious demographic distress.

After World War II, the slogan “Populate or Perish” began to spread throughout Australia. But not everyone was welcome, including the country’s Indigenous peoples and Australia’s neighbors to the East, who were seen as a threat pressing in from overpopulated territories. The white elite wanted to draw on Westerners, preferably English, Dutch, Americans, Germans and Poles. Mediterranean immigrants, however, could provide much-needed labor. During the three-day journey, Italian and Greek women who “were going to get married, or had already been married by proxy” also boarded the planes carrying the Spanish women, explains Natalia Ortiz Ceberio, coordinator of Hispanic studies at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), in a telephone conversation from Sydney. For her, “the real deception” of the authorities towards the Spanish women “was that no one informed them of the cost of returning… of how impossible it would be to pay for the return ticket,” which was around 3,000 pesetas, or €18.

Group of ‘martas’ in Madrid in 1962, ready for the fifth flight of the plan that year.Archivo de la familia Aberasturi Erezuma

Group of ‘martas’ in Madrid in 1962, ready for the fifth flight of the plan that year.Archivo de la familia Aberasturi Erezuma

“Without immigration, a future of the Australia we know will be both uneasy and brief. As a nation, we shall not survive,” warned Immigration Minister Arthur Calwell in his speeches, as reflected by Javier Castro and Ortiz Ceberio in the documentary El avión de las novias (The Brides’ Plane). At the same time, Australian newspapers of the era advertised Spaniards as a “cultured and proud people.” The UNSW professor is the author of several works on the sense of identity of emigrants and on the travels of Spanish women, such as El Plan Marta (1960-63), a book published by Dykinson and edited by María Pilar Rodríguez. The researcher began tracking down stories of martas more than a decade ago, after reading in another volume, Operación Canguro (Operation Kangaroo), by Ignacio García, that there had been a flight carrying women following an initial migratory experiment with men, who traveled by boat. Since then, Ortiz Ceberio — an emigrant to Australia of Basque origin and founder of the Spanish Film Festival, which she directed for 15 years in both Australia and New Zealand — ended up discovering in the archives of the Episcopal Conference that, in reality, “there had been at least 17 flights.”

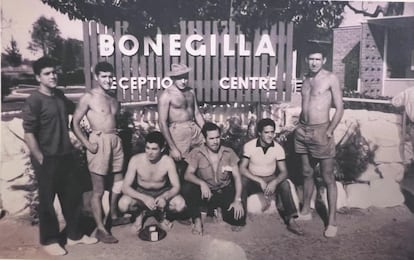

Spanish youths from Operation Kangaroo at the Bonegilla migrant reception camp, built after World War II in Victoria.Archivo de la familia de Vulcano Mateo

Spanish youths from Operation Kangaroo at the Bonegilla migrant reception camp, built after World War II in Victoria.Archivo de la familia de Vulcano Mateo

Since the first trip on March 11, 1960, “815 martas arrived in three years,” of whom the author has located and interviewed more than 100. Some signed up without understanding the contract. Many were unable to even locate Australia on a map. Josefina González’s suitcase had no address: she simply wrote her name and “Australia” on the label, but she arrived with it on July 14, 1960. The truth is that neither she nor her companions really knew their destination. Over the years, the method changed, but those who were there at the beginning remember being taken to a church, lined up, and then Australian women would choose which girl they would take to serve in their homes, “like sheep at the market.” Those who did not go with families were taken to work for Catholic congregations.

Young, unmarried, healthy, and officially Catholic

The machinery was set in motion after a visit to Spain in 1959 by the Cardinal Primate of Australia, and soon the recruitment drive was helped by the consulates, the Spanish Emigration Institute, the Episcopal Conference on Migration, and a dense network that reached even the most remote parishes of Spain through Catholic Action and the Christian Workers’ Youth. The candidates were first selected here. They had to be young, unmarried, healthy, and officially Catholic. But a few were not, in reality, as devout as desired, and what they really longed for was to free themselves from the rigidity of family life and the feminine roles instilled by Francoism. Some were single mothers who left their children in Spain with the idea of bringing them over later.

They underwent a medical examination and a “training” course at the convent of the Madres Reparadoras in Madrid, where they were taught efficient domestic service, Australian customs and schedules, and survival English for a housekeeper: it was enough to know that a spoon was called a spoon and a mop was called a mop. The important thing was to be able to name the most basic kitchen and cleaning utensils, because the rest, if their life was going to be eminently domestic, did not matter. The boys who had gone to cut cane, on the other hand, had received a much more comprehensive training through the Good Immigrant’s Manual, which they could learn during the month-long boat trip.

Mari Paz Moreno says in the documentary that she signed up because she “wanted to learn English.” She was a young woman with an education, working at the news agency Europa Press, and eager to see the world. When she arrived in Australia, she discovered that the urban environment was “a graveyard” where, at 6 p.m., there was nowhere to “have a coffee.” But on the other hand, she concludes, “in many ways” Australia “was a country with a future,” while Spain, at that time, “was a country with a past.” The history of Australia was thus written with the names of women such as Carmina Álvarez Patallo, Juli de la Rosa, Puri Paredes, Mari Cruz Vázquez, Maruja Vesuña, Irene González, Cruz Pereira, Ana María Godino, María José Ugarte, Teresa Santamaría, Leontina García, Genoveva Mateo, María Cruz del Álamo, Julia González and Begoña Zubiaur, and men such as Francisco Javier Montero, Vulcano Mateo, and Eulogio Altuna, who at 93 years old, now back in his home city of San Sebastián, in northern Spain, is the living memory of the cane cutters.

Group of ‘martas’ at the Madres Reparadoras school in Madrid on September 30, 1961.Archivo de Julia González.

Group of ‘martas’ at the Madres Reparadoras school in Madrid on September 30, 1961.Archivo de Julia González.

Ortiz Ceberio explains that “the first ones did not pay for the one-way ticket.” The next group, following the pull effect, “had to pay for part of it.” The rest was paid for by the various administrations interested in these migrations. If they were homesick and wanted to return before the two years had elapsed, the martas had to pay back their debt, in addition to the return fare. Despite everything, for many, the outlook in Spain was no better, and when the agreement between the two countries ended, “there were hundreds and hundreds of women asking to come to Australia,” says the researcher.

Group of ‘martas’ in Madrid in 1962.Archivo de la familia Aberasturi Erezuma

Group of ‘martas’ in Madrid in 1962.Archivo de la familia Aberasturi Erezuma

Generally, those who were already there had “kept quiet” about how hard it was to work in houses in a country whose language they did not know. To provide “spiritual support” and help the martas with any problems that arose at work, or when their spirits flagged, the Church sent three “lay sisters”: Paquita Bretón, María Luisa Erro, and Mari Carmen Cervera. It was known as “immigrant sickness or Australia sickness,” says the professor, the “depression” and “despair” of being “far from everything,” with no escape from the vast island, at a distance that was “impossible to overcome.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition