Ztorski + Ztorski, I. 101 white rat pelts, 24 ct gold.

Ztorski + Ztorski, I. 101 white rat pelts, 24 ct gold.

The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition 2025 uses Dialogues as its theme in a motion to respond to an era marked by deepening divides: social, political, and cultural. In the face of rising polarisation, the show looks to art’s ability to spark conversation and create space for coexistence, however messy or unresolved.

And speaking of mess: prepare to queue, elbow your way through crowds, and crane your neck at the works hung salon-style, many of which are so high up they verge on theoretical. It’s hard not to wonder about hierarchy in an exhibition that prides itself on openness — where professionals, amateurs, the famous, and the not-yet-known all share wall space. Yet, despite this democratic premise, “high art” still looms, literally and figuratively.

There’s a strong showing of archive works this year too, including a few déjà vu moments from the Michael Craig-Martin show of 2024. While the intention may be dialogue, at times it feels a bit like a monologue echoing from the institution itself.

Of the over 1,700 works on exhibit, we selected 10 pieces that caught our fancy.

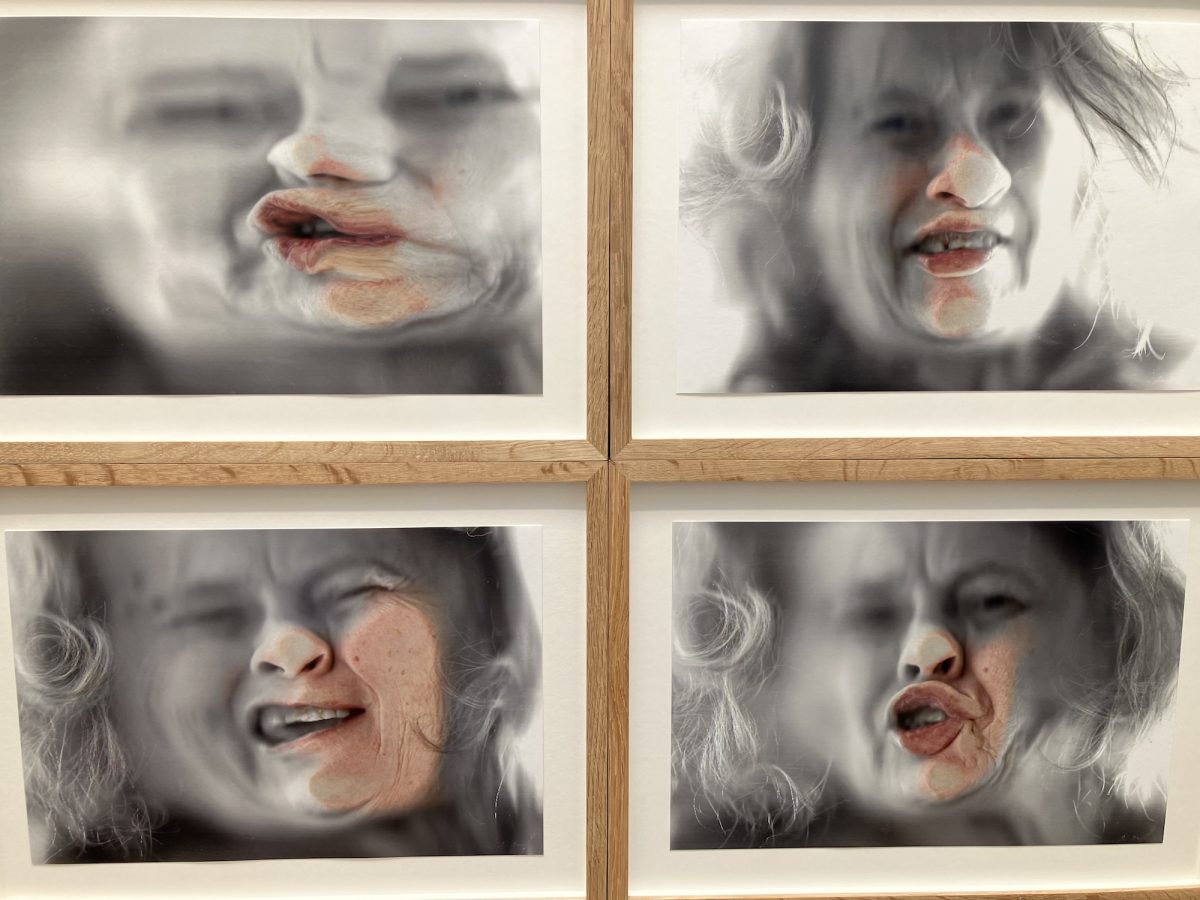

1642: Anne Bean, All Communication Is Translation. Anne Bean, Twelve face paint prints and twelve scans.

Anne Bean, Twelve face paint prints and twelve scans.

In 1982, Anne Bean staged a performance titled All Communication is Translation, in which she chanted that very phrase—one syllable at a time—while smashing her ever-distorted, paint-smeared face into sheets of paper. By the end, she’d created a dozen raw, vivid and grotesque ‘self-portraits,’ each silently mouthing a single syllable like a visual stutter: “all,” “com,” “mun,” “i,” “ca”…

Twelve portraits. Twelve syllables. Twelve incomplete truths. The idea that a single frame could stand in for a fluid, embodied act becomes the very tension of the work: translation as distortion, portraiture as reduction.

Bean’s practice persistently questions whether anything can ever be fully captured—be it identity, language, or experience. Her work exists in the gap between the thing and its representation, reminding us that meaning is always partial, provisional, and beautifully flawed. MORE

816: Alexandre Da Cunha, Broken IV. Alexandre Da Cunha, Scourer, visor, ink, acrylic emulsion and polymer on canvas.

Alexandre Da Cunha, Scourer, visor, ink, acrylic emulsion and polymer on canvas.

In the aftermath of a pandemic obsessed with cleanliness and control, even a particular shade of blue—clinical, disposable, unmistakable—has come to symbolise an entire era. Alexandre da Cunha’s work offers a quiet resistance to this impulse to sanitise and erase. By pointing to everyday objects—mops, mixers, walking sticks—he lets their past lives linger.

These objects arrive carrying the weight of use, memory, and association. Da Cunha doesn’t disguise that. Instead, he invites us to see the poetry in what’s worn, the beauty in what’s been handled, repurposed, or discarded. As material culture is ever more curated to a glossy, perfect finish, his sculptures embrace residue over polish—suggesting that healing might come not from starting fresh, but from acknowledging what remains. MORE

1723: Robert Mach, New World Man.  Robert Mach, Plastic, wood and foil confectionary wrappers.

Robert Mach, Plastic, wood and foil confectionary wrappers.

Though working across various media, in recent years he has turned increasingly to the use of foil wrappers—bright, reflective skins peeled from the everyday. Using iconic materials like Tunnock’s Teacake foil, he ‘gilds’ sculptures and creates two-dimensional works that shimmer with both humour and critique.

But the wrapping isn’t about concealment. It’s a way of revealing—drawing attention to the overlooked textures of ordinary life. By covering objects in this glitzy skin, he exposes their essence: cheap, familiar, mass-produced, and deeply embedded in contemporary consumer culture.

In wrapping the throwaway, he reframes it—elevating the banal into something celebratory, strange, and quietly profound. MORE

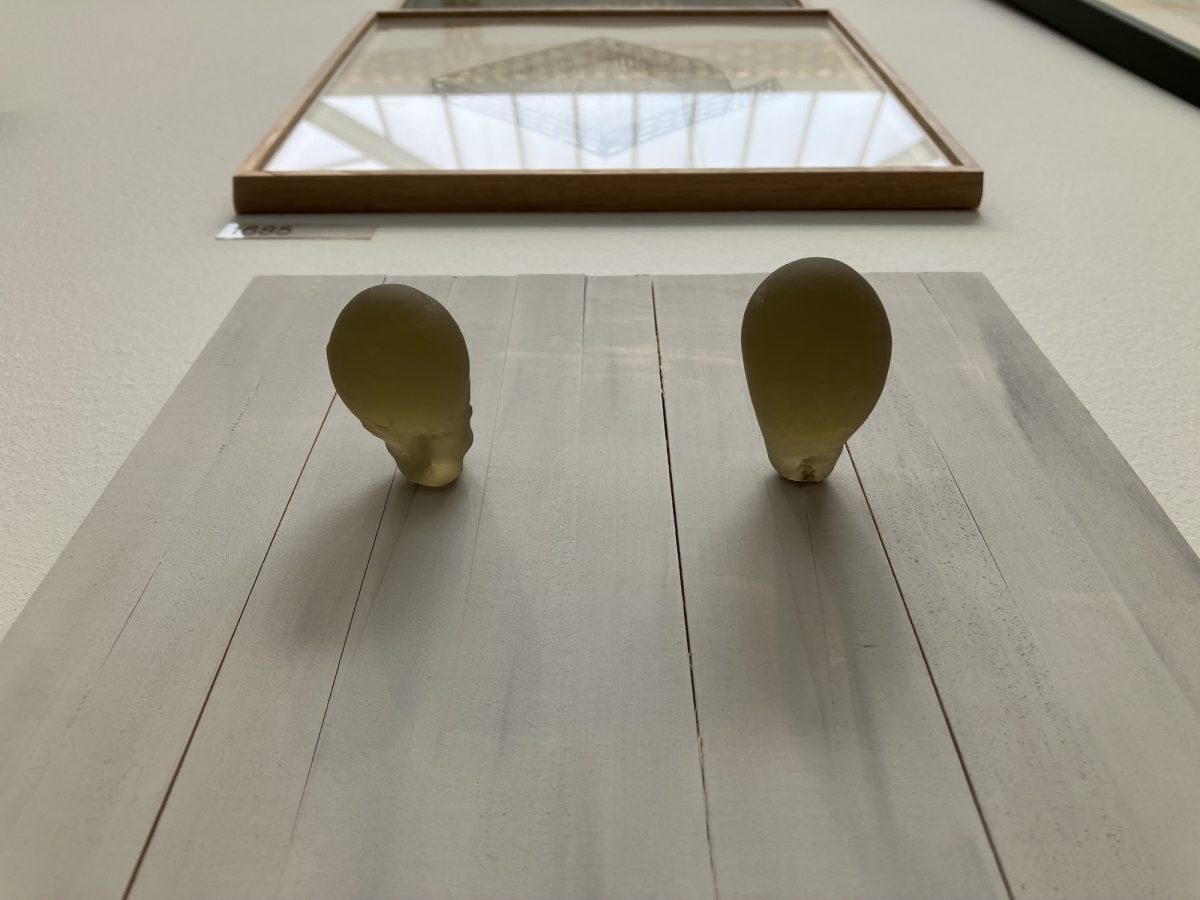

1684: Alison Wilding, Those. Alison Wilding, Gesso on poplar wood, cast glass.

Alison Wilding, Gesso on poplar wood, cast glass.

Alison Wilding’s abstract sculptures don’t give everything away at once. They like to play hard to get. Sometimes you have to look at them from another angle: crouch down, or walk away and give them the side eye just to catch their secrets. The works walk a fine line between playful and serious, bold and understated.

Wilding mixes materials with cheerful disregard for hierarchy: found bits and handmade parts, the expensive and the everyday—all warrant equal billing in her quietly surprising constructions. Over the years, she’s racked up serious recognition as well: twice shortlisted for the Turner Prize, elected a Royal Academician in 1999, and awarded an OBE in 2019. Not bad for someone whose sculptures seem happiest when keeping you guessing. MORE

348: Frances Featherstone, I Don’t Want to Talk About it. Frances Featherstone, Oil on linen.

Frances Featherstone, Oil on linen.

Frances Featherstone’s richly decorative paintings capture quiet, private moments—figures curled in bed, lounging on sofas, or gazing out of windows. Viewed from above, her subjects appear lost in thought, surrounded by layers of vivid, patterned fabrics. This bird’s-eye perspective lets her explore the lush interplay of textiles, clothing, and flooring, turning domestic space into a tapestry of comfort and visual delight.

Her use of intricate patterns often recalls Indian block prints—an echo of the growing cultural exchange reflected in the UK’s recent Free Trade Agreement with India, which eliminated import duties on textiles. Trained at the University of the West of England and formerly a Senior Designer at the BBC, Featherstone brings a strong sense of staging to her work, blending figure and setting to quietly tell stories of warmth, solitude, and beauty. MORE

Caragh Thuring, Acrylic, oil graphite powder, charcoal on gessoed linen.

Caragh Thuring, Acrylic, oil graphite powder, charcoal on gessoed linen.

Born in 1972, and based in London, UK, Caragh Thuring works with a refined visual language that balances minimal elements with a distinctive mix of figuration and abstraction. Drawing on a bold yet modern colour palette, the work often personifies symbols, infusing them with emotion, ambiguity, and narrative potential. Thuring received a BA in Fine Arts from Nottingham Trent University in 1995. MORE

1410: Andrew Ekins, Tête-à-tête.  Andrew Ekins, Oil on paint skins, used clothing.

Andrew Ekins, Oil on paint skins, used clothing.

Andrew Ekins treats painting as a living thing—feral, physical, and unpredictable. He lives and works between the urban grit of London and the ancient geology of North Wales — two landscapes that shape his richly layered artworks, which fall between sculpture and painting. Drawing on nature’s textures, fungal growths, and the sediment of human presence, his work revels in the tension between beauty and decay, the sublime and the abject.

Thick with painterly mass, his surfaces are built up like compost heaps—strata of colour, gesture, and material that feel at once joyful and grotesque. Joy exists here too, in the sheer excess of texture and colour, in the way fungus might bloom on ruin. His work has been celebrated at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition, selling on the first day. MORE

877: Andy Seymour, The Long Distance Gamer. Andy Seymour, Acrylic.

Andy Seymour, Acrylic.

Earlier this year, the nation (and Netflix audiences worldwide) became fixated on Adolescence, a series that sent morning talk shows into a frenzy over knife violence, emoji codes, and the algorithmic rabbit holes of teenage life. The conversation quickly turned to loneliness, disassociation, and a generation seemingly adrift—not just from others, but from themselves.

This painting captures that very sense of suspension: a child, present but vacant, their gaze retreating inward. The artist is near, yet worlds apart, as if bearing witness to someone already slipping out of reach.

We know nothing about this child, and yet it’s hard not to project: misogyny, male rage, incels, the manosphere, social media—buzzwords now stitched into any discussion of boys, young men, and the toxic currents shaping them. The painting doesn’t explain, but it quietly holds all of it—the noise, the fear, and the aching silence beneath. MORE

789: Li?a Ani?, London Brick Slippers (Shoe Size 4). Li?a Ani?,

Li?a Ani?,

There’s an old saying: “You’re a brick”—solid, dependable, built to last. Everything a pair of flimsy, synthetic platform slippers from the high street decidedly isn’t.

Fashion’s absurd contradictions take centre stage in several works, particularly in Li?a Ani?’s London Brick Slippers. Enchanting in their total impracticality, these sculptural hybrids are both humorous and haunting. Labeled with a mass-market brand and constructed from synthetic materials, they nod to the throwaway nature of fast fashion—designed for trend cycles, not longevity.

The irony bites deeper when paired with the image of the brick: the ultimate symbol of permanence and strength. Ani? playfully highlights the disconnect between what we wear, how it’s made, and how quickly it’s replaced—despite the environmental afterlife of the materials we leave behind. MORE

1713: Ztorski + Ztorski, I. Ztorski + Ztorski, I. 101 white rat pelts, 24 ct gold.

Ztorski + Ztorski, I. 101 white rat pelts, 24 ct gold.

There’s a certain magic in wondering what on earth possessed someone to do that? The first person to eat a lobster, for instance—what kind of curiosity (or hunger) drives someone to crack open sea armour for a morsel of meat? Or consider the little-known rat hunters of New York: a group that patrols the streets with dogs, chasing rats not for pest control, but for sport. Their efforts don’t dent the rat population, but that’s not really the point—it’s ritual, meaning-making, absurd devotion.

We’re living in strange times. The body is glitching; the mind is expanding. AI hurtles ahead, and the line between tool and toolmaker starts to blur. As we inch toward the singularity, the question arises: will the machines serve us, keep us as pets, or just move on without us—like a butterfly shedding its chrysalis with zero sentiment?

In I, 101 white rats stand on their hind legs, perfectly preserved, their hollow forms lined with 24-carat gold. They form a circle low to the ground, gazing upward towards the viewer. They don’t squeak or scurry, but their silence hums with judgment. Gold-plated and emptied, they channel everything the rat has come to mean: lab subject, outsider, survivor, scapegoat.

You could read them as a warning. Maybe they’re artefacts from a future that’s already written, where we’ve traded our flesh for code and left our bodies behind. Or maybe they’re just here to remind us, with glinting little stares, that some experiments can’t be undone.

To coincide with the RA Summer exhibition, Ztorski + Ztorski have created a limited edition multiple, “The One“. MORE

*Last Chance: RA Summer Show 2025 closes this Sunday 17th August

royalacademy.org.uk/summer-exhibition-2025

CategoriesTags