Jill Angood and Chris Pyke.

Chris Pyke.

Poetry has become a big part of how I understand the world, a place to process, to listen, to give shape to what I’m feeling. When I first joined a poetry club at the Rutland Arms in 2018, I didn’t expect that it would open up creative friendships, or that it would become a way to navigate grief.

One of those friendships was with Chris Pyke and his partner, Jill Angood. Chris and I recently took a walk across Wadsley Common and talked about creativity, love, loss and how compiling Jill’s poems into a published pamphlet after her death became a deeply human act of remembrance. “Creativity doesn’t fix grief,” Chris said. “But it can shape it.”

Jill had been writing poetry for decades, long before she

and Chris met in 1977. Her writing was rooted in the Fens in the east,

particularly the Isle of Ely, where she grew up. That watery, flat

landscape was central to many of her poems.

From our front window mostly fields

ruled by dykes and ditches

lines of poplars piercing the big sky

lessons in perspective.

Jill was a regular at writing groups including Heeley Women

Writers, a long-running workshop led by Nell Farrell. Before she died,

she had begun work on a pamphlet with help from Suzanna Evans at the

Poetry Business, but it had been paused during a house move. “She left behind a huge body of writing,” Chris told

me. “It was all in one place. [Local poet] Sally Goldsmith and I decided we’d like to

finish the pamphlet she’d started.”

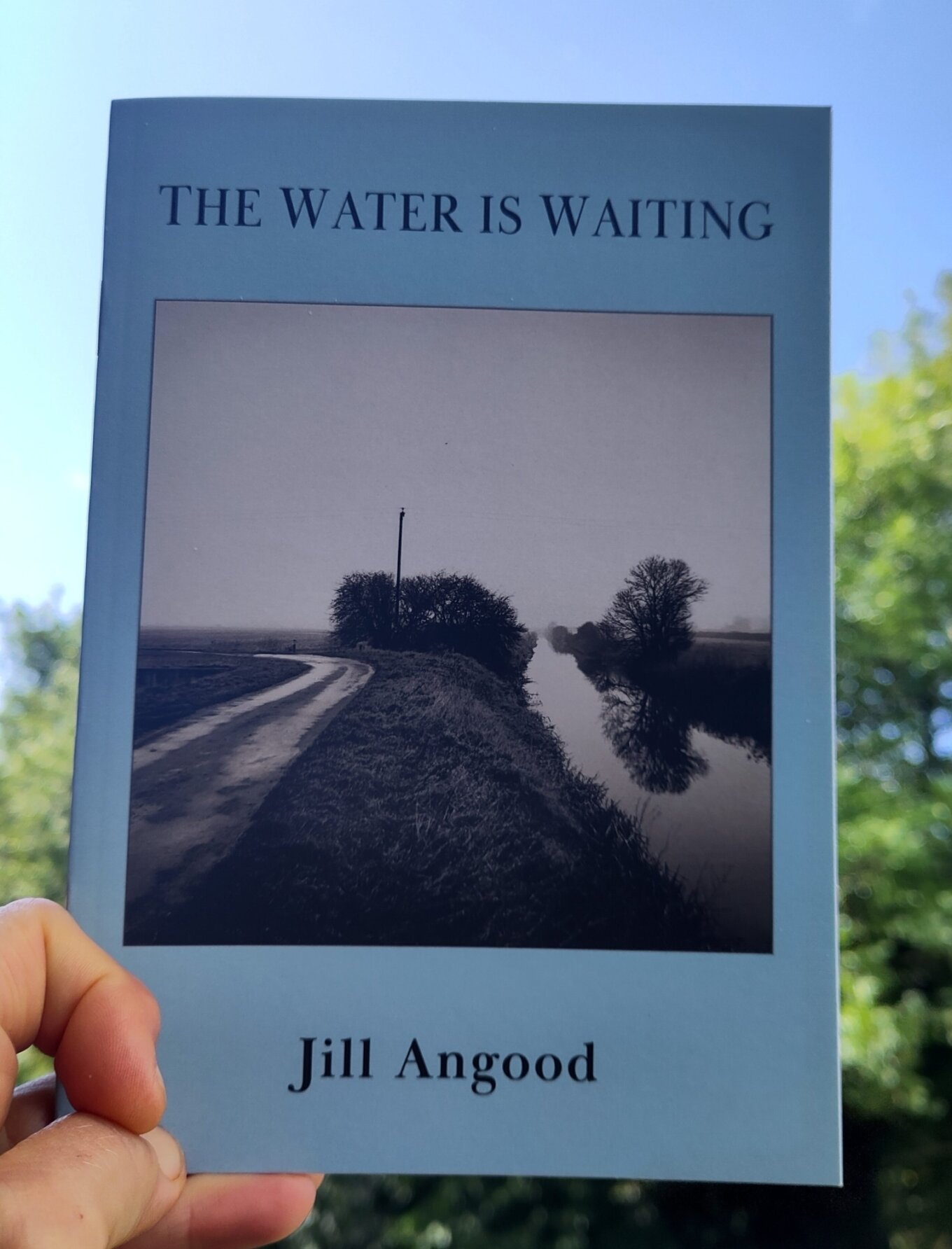

With support from Nell and Suzanna, they carefully edited the poems, added a few more recent ones, and published The Water is Waiting this spring. The title is taken from the opening poem. “We launched it at the Samuel Worth Chapel at the

General Cemetery. It felt right. She loved that place, and we lived

nearby when we first moved to Sheffield.”

The collection offers a vivid portrait of Jill’s heritage:

the flatlands, her family, the cold and the constant presence of water. “People who know that landscape really recognised it,” Chris told me. “She captured its flavour.”

THE NENE

Forced out of its natural bent

held tight in a girdle of wooden ribs

dredgers kept it clear

for wheat from the Baltic, timber from Norway

and sailors who gave that part of town a bad name

Pulled by the moon into eddies and swirls

fast turning tides left muddy banks

in naked pockmarked shiny shame

then one full moon the waters rushed back

and high tides swept the Chinese chippy away

A river held in, longing to escape

spun into whirlpools of slime and sludge

separating old town from new town

Boys Grammar from Girls High

At the end of that summer

we stood on the bridge in our pastel dresses,

white collared and cuffed

giddy with the future

emptied our satchels over the parapet

watched our red berets swirl out to sea

Since Jill’s death, Chris has found comfort in writing and dancing. He wrote several poems around the time of the funeral,

including one after sitting in the undertaker’s viewing room with his

daughter. “We didn’t open the coffin. I wrote about what it meant not to take a last look.”

He also dances regularly, specifically 5Rhythms, a free-form movement practice that lets emotions move through the body. “There’s rhythm in both dance and poetry. I’ve felt joy, anger and grief all within one session. It’s profoundly

cathartic.”

Chris and Jill on the day of their civil partnership.

Chris Pyke.

Chris also helped organise a men’s grief event under the Compassionate Sheffield banner. Nearly 30 men attended. “Grief is universal, but every story is different. Some spoke in groups, some just listened. People were glad to have the space.”

Grief, we agreed, doesn’t arrive in predictable ways. Sometimes it doesn’t appear where you expect. Not at a grave or a memorial, but when you’re sweeping the floor, or when a song from years ago plays on the radio. “It catches you off guard. And I think it’s a gift to be able to cry.”

Grief doesn’t disappear – it changes shape. For Chris, Jill remains woven into everyday life. “Any joy I feel now was kindled in the joy we had. It’s a continuous thread.”

I’ve come to understand that too. When my mum was diagnosed with cancer, and later when she died, I struggled to make sense of what I was feeling. It was poetry that helped. Some poems seemed to speak directly to me. Writing became a release, a way to name what I couldn’t express.

We don’t always talk about grief in society, but creativity can help us approach it sideways, whether this is through art, music or movement. Even when there are no words, there’s still the act of making. A poem, a journal entry, a dance. Something that says: I was here. They were here.

Creativity won’t erase grief, but it can help us live with it. It connects us to the people we’ve lost – and to ourselves.

Learn more

The Water is Waiting by Jill Angood is available to buy from Rhyme & Reason.