Donald Trump appeared to confuse geography and history on Monday, saying on television that he planned to meet Vladimir Putin “in Russia” on Friday for their much-anticipated, high-stakes summit.

It was the latest in a series of verbal slip-ups by the US president – though had he made it a century and a half earlier, it would have been true.

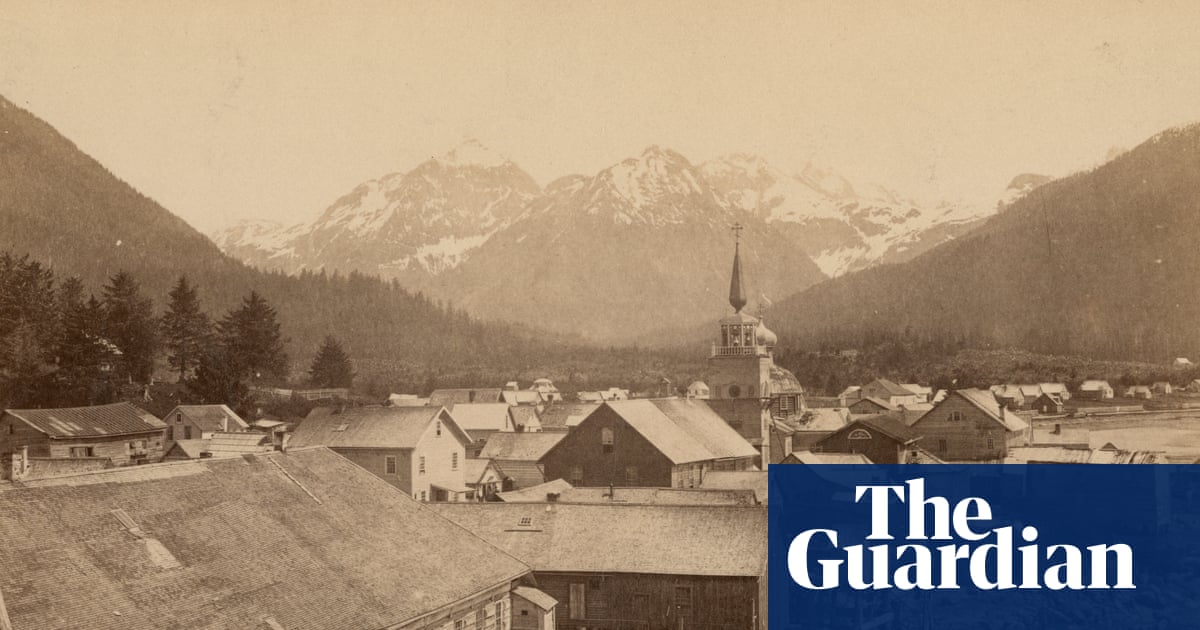

Alaska, with Novo-Arkhangelsk as its regional capital, remained part of the Russian empire under Tsar Alexander II until its sale to the US in 1867.

When Putin’s jet touches down in Alaska, he will be greeted by traces of Russia’s former presence. From the wild, rugged shores of Baranof Island to Anchorage, the state’s largest city, Russian Orthodox churches with their distinctive onion-shaped domes still dot the landscape.

St Michael’s Cathedral, a Russian Orthodox church in Sitka, Alaska. Photograph: Michael Maslan/Corbis/VCG/Getty Images

Russia’s foothold in Alaska began not with armies, but fur. In the mid-18th century, merchants and adventurers pushed east across Siberia, spurred by the promise of lucrative sea otter pelts. By the 1780s, Catherine the Great had authorised the creation of the Russian-American Company, granting it a monopoly over trade and governance in the territory.

Alexander Baranov, a hard-driving merchant, consolidated Russia’s hold on the region in the late 18th century, expanding settlements and ruthlessly suppressing resistance, most famously from the native Tlingit, who gave him the grim nickname “No Heart”.

Russian Orthodox priests soon followed, establishing missions and building churches. In New Archangel (now Sitka), they raised St Michael’s Cathedral, its green dome rising against a backdrop of glaciers, still anchoring the town’s view more than 150 years later.

But by the mid-19th century, the Russian empire had come to see Alaska as more of a liability than an asset, and began quietly seeking a buyer. In the wake of its humiliating defeat in the Crimean war, the territory had become a drain on St Petersburg’s finances, compounded by mounting fears over Britain’s expanding naval presence in the Pacific.

In a letter to a friend in July 1867, Eduard de Stoeckl, the Russian envoy in Washington and chief negotiator of the sale, admitted: “My treaty has met with strong opposition … but this stems from the fact that no one at home has any idea of the true condition of our colonies. It was simply a matter of selling them, or watching them being taken from.”

The sale of Alaska emerged as a rare diplomatic win-win: for Russia, a way to recoup cash, gain a new, emerging ally across the Atlantic and sidestep a potential conflict with Britain; for the US, an opportunity to forestall European encroachment and assert its growing influence in the Pacific.

Still, when the Russian empire agreed the sale in 1867, few on either side of the Pacific saw it at first as an outright triumph.

In St Petersburg, it was viewed by some as the latest imperial humiliation. The colony, remote and costly to supply, had never been a jewel of the empire, yet the price – $7.2m – struck many as insultingly low.

The liberal paper Golos dismissed the transaction as “deeply angering all true Russians”.

“Is the nation’s sense of pride truly so unworthy of attention that it can be sacrificed for a mere six or seven million dollar[s],” the paper wrote.

Across the US, the secretary of state, William H Seward, who negotiated the treaty, was ridiculed for spending what critics saw as an unreasonable sum on a frozen wilderness. The New-York Daily Tribune dismissed the acquisition as “the nominal possession of impassable deserts of snow”.

“We may make a treaty with Russia,” its editorial complained, “but we cannot make a treaty with the North Wind or the Snow King.”

Portrait of a hunter in Alaska, 1910-20. Photograph: Marka/Touring Club Italiano/Universal Images Group/Getty

Others wondered if the price was suspiciously low, and whether Russia had simply palmed off a worthless scrap of territory. “Russia has sold us a sucked orange. Whatever may be the value of that territory and its outlying islands to us, it has ceased to be of any to Russia,” the New York World wrote on 1 April 1867.

Yet that perception would soon be dramatically overturned. The gold rushes of the late 19th century, and the discovery of oilfields decades later, transformed what had once been mocked as folly into one of the US’s most resource-rich territories – and one of history’s great bargains.

The cheap sale remained etched in Russian memory and has occasionally inspired fringe nationalist calls to reclaim Alaska. In 1974, when Americans protested against the low price the USSR paid for wheat, the Soviet trade official Vladimir Alkimov drily noted that Alaska had been sold for only $7m.

In 1867, the mood was different. For a short time, the Alaska sale opened a fleeting chapter of warmth between Russia and the US.

Russian and American diplomats sign the Treaty of Cession, under which the US bought Alaska from the Russian empire in 1867. Photograph: Pictorial Parade/Getty Images

The New York Herald lauded in 1867 what looked like a potential new ally in Russia, writing: “The cession of Russian Alaska becomes a matter of great importance. It indicates the extent to which Russia is ready to carry out her entente cordiale with the United States,” the paper continued.

That warming of ties would culminate in 1871, when Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich led a naval squadron to New York, where he was greeted with military parades, gala receptions and civic honors.

When Trump and Putin meet in Alaska this week, the backdrop will be the prospect of a historic renewal of ties. For Kyiv, the hope is that this time such warmth will not come at the expense of its territory – and that the era of trading land like currency in great power deals is in the past.