Claire Wilson, 66, grew up in central London on an estate that had tennis and badminton courts and a swimming pool. Her parents were not wealthy financiers. Her father, Robert, worked for Her Majesty’s Stationery Office and took part-time jobs to get by. Her mother, Doris, worked in accounts using a Comptometer, an early version of an electronic calculator.

In the 1960s the Wilsons’ low income meant they qualified to live in a council house on the Golden Lane Estate in the City of London. Built in the 1950s on a bombsite on the northern edge of the Square Mile, it was designed by the same architects — Chamberlin, Powell and Bon — that went on to build the groundbreaking Barbican Estate next door. “It was an amazing estate in that era,” Wilson remembers fondly.

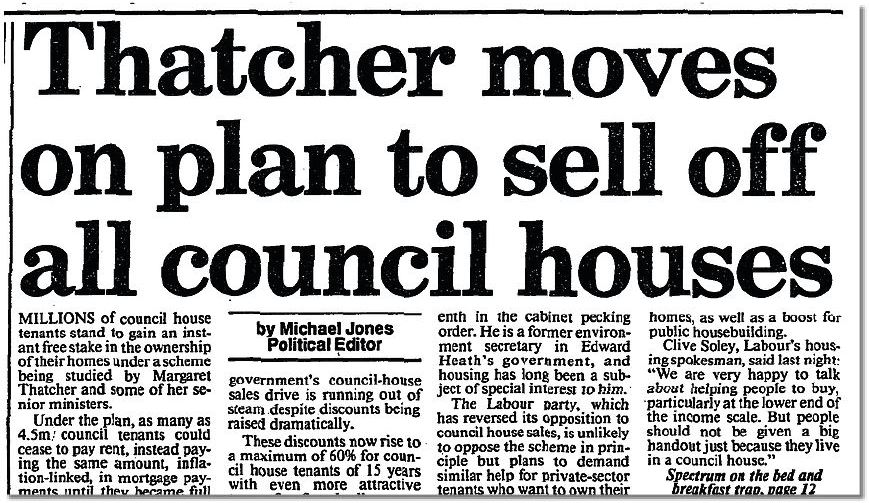

Two decades later, the Wilsons were presented with a life-changing opportunity. They were among Britain’s six million council tenants given the “right” to buy their homes from the local authority at a discounted price — a policy of Margaret Thatcher’s government when it came to power in 1979. They wouldn’t just be homeowners; they would be joining Thatcher’s vision of a “property-owning democracy”. The Wilsons had their reservations. “My father hated Thatcher,” Wilson says. “There was a part of him that thought, if she had anything to do with it, there must be a catch.”

In the end it was the Wilson children who convinced their parents to buy their three-bedroom flat in 1981. Security was the motivating factor, not profit. Doris had recently inherited enough money from her stepmother to buy it mortgage-free, which, her children explained, would protect them for ever against rising rent or mortgage payments. The flat was theirs for just £16,000 — £35,000 less than its value on the open market.

The Wilsons paid £16,000 in 1981 for their right-to-buy flat on the Golden Lane Estate in the City of London, above, and sold it in 2000 for £240,000

GETTY IMAGES

Claire Wilson with her mother, Doris

Twenty years later, Robert and Doris asked Claire to sell the flat. It was snapped up in 2000 for £240,000 — a 1,400 per cent increase. The sale set the couple up for life. It meant they were able to buy a home for their retirement outright. Robert died and Doris, now aged 95, is using her savings to fund her care. Today there is a two-bedroom flat for sale on the Golden Lane Estate for £750,000, a 4,488 per cent increase on the 1981 price.

Right-to-buy will be 45 years old in October, and its effects still reverberate through the housing market. A third of England’s public housing was sold off between 1979 and 1990. If asked to nominate Thatcher’s biggest sell-off, most people would mention British Airways, British Telecom or British Gas, but council housing was bigger than any of them. In total more than two million council homes have been sold through right-to-buy, worth £371 billion. This represents the biggest transfer of public property into private ownership in UK history.

The policy played a pivotal role in giving many baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) a foothold on the property ladder. Not only could they now own their own properties, they were free to make home improvements too — adding conservatories, extensions, loft conversions and value over time. They benefited again from the house-price boom of the early 2000s. It is no exaggeration to say that right-to-buy — along with the buy-to-let boom of the early 1990s — changed the way Britain viewed housing: from a right under the social contract between citizen and state to a commodity to be coveted and traded.

The scheme was controversial from the start, with the housing charity Shelter and the Royal Town Planning Institute warning about the long-term impact on the affordability of housing, worsening conditions for low-income tenants, and councils losing control of their housing stock. These homes were sold at an average discount of 44 per cent, representing nearly £194 billion in lost value to taxpayers, a report by the think tank Common Wealth revealed earlier this month. The organisation’s chief economist, Chris Hayes, said local authorities were forced to conduct “fire sales by central diktat” that “denied them a reasonable return on those assets. It was an unrepeatable state handout on an unprecedented scale.”

Today the Labour government is reforming and restricting access to the scheme, with the stated aim of giving councils time to replenish their depleted stock. The number of council homes bought through right-to-buy has already reduced from 970,000 in the 1980s to 45,000 in the past five years. Under the revised scheme the buyers’ discount is being cut from 35 per cent to between 5 and 15 per cent. To qualify, tenants need to have lived in their council house for ten years or more, up from three at present. The reforms have been labelled an “attack on aspiration” by critics.

Looking back nearly half a century on, the scheme is easy to criticise. When it was born, however, it was a revolution in social mobility. Was it always destined to fail or could it be revived if handled with care?

• Council house lists: 25-year wait as thousands of homes sit empty

The philosophy behind right-to-buy

Right-to-buy is branded in Britain’s consciousness as a key tenet of Thatcherism. In fact, Thatcher had less to do with it than many people think. Ted Heath, the Conservative prime minister from 1970 to 1974, had wanted to include right-to-buy in his manifesto for the October 1974 election. Thatcher was his shadow environment secretary at the time and she was opposed to it, saying it would be unfair to those who had saved to buy their homes. “What will they say on my Wates estates?” she said, referring to new housing developments built by the family-owned property giant.

Right-to-buy didn’t make it into Heath’s manifesto because high interest and mortgage repayment rates rendered home ownership unrealistic for many tenants. But the idea didn’t die. Thatcher, who was elected Tory leader in opposition in 1975, still hated it when it was proposed by colleagues such as Peter Walker, formerly Heath’s environment minister. She “felt it would upset ‘our’ people who had struggled to pay their mortgages”, Walker wrote in his 1991 memoir, Staying Power.

Margaret Thatcher visits the Paterson family at their home in Harold Hill, Greater London, which they bought from the council in 1980 for £8,315 — a 40 per cent discount on the market price

ALAMY

It was clear on the doorstep, however, that council tenants wanted the chance to own their own homes, so Thatcher included it in her 1979 election manifesto. But even then it wasn’t a flagship policy, and there was little discussion about how the proceeds would be spent.

Michael Heseltine, Thatcher’s environment secretary and one of right-to-buy’s biggest champions, was charged with implementing it. He said the policy had two main objectives: to give people what they wanted and to scale back state interference in their lives. He believed Britons have a “deeply ingrained desire for home ownership” and this should be encouraged because it “stimulates the attitudes of independence and self-reliance that are the bedrock of a free society” and “ensures the wide spread of wealth”.

There was a strongly held belief in the Conservative Party at the time that turning council tenants into homeowners was a key step towards converting them into Tory voters. This culminated in the “homes for votes” scandal of 1989. An exposé by the BBC’s Panorama programme revealed that Shirley Porter, the Conservative leader of Westminster city council, attempted to gerrymander the local vote between 1987 and 1989 by selling off council housing to tenants at a discount in marginal wards, while relocating homeless families to areas where the vote was “safe”. Right-to-buy and a new “designated sales” policy were used, but this was ruled to be illegal and Porter was found liable. She eventually settled with the council for £12.3 million.

Among those who argued against right-to-buy in the 1980s was Alan Murie, now 79 and emeritus professor of urban and regional studies at Birmingham University. It wasn’t councils selling housing to tenants that concerned him — they had been doing that since the 1930s — but that they were forced to sell at such a discount and the capital generated wasn’t reinvested in housing. The discounts have never been funded — the properties are sold by councils at a loss.

“It’s an incredibly short-sighted, short-term approach to public finances,” Murie says today. “You’re selling the family silver to fund current expenditure. You should only sell assets to invest in other assets. Every government afterwards wants to keep taxes down and maintain some level of public spending, and they can’t understand why they can’t make it stack up. They forget that the way in which [Thatcher] managed to do it was by selling public assets, which you can only do once.”

Under the original scheme local authorities were also obliged to offer mortgages to tenants who could not get one from a bank or building society. This legal duty was abolished in 1993 but some local authorities continued to offer mortgages voluntarily for a few more years. These were funded through council finances, which were, as now, a mixture of public grant and private investment and asset management. Local authority mortgages no longer exist, and right-to-buy tenants today have to get a privately funded mortgage.

Michael Heseltine, who spearheaded the original campaign, handing the McCarthy family their title deeds at a ceremony in Earls Court, 1980

GETTY IMAGES

The boomer winners

Pioneering council tenants such as Doris and Robert Wilson, who used the right-to-buy scheme to buy their homes in the 1980s, were the biggest winners. On average those early buyers paid £11,903 (typically with a £10,140 discount) for their homes, which have grown in value by £168,164 (£190,207 in today’s money), according to research from the estate agency Savills.

Today, the over-60s control more than half of the UK’s housing wealth, while the over-75s control almost a quarter, according to Savills. This isn’t all down to right-to-buy, of course: house prices were typically only three times a worker’s annual salary, whereas now they are closer to eight times annual earnings. The under-35s hold just 6 per cent of the UK’s housing wealth, but some of it is already trickling down in the form of gifted deposits. Last year, just over half of first-time buyers bought their home using cash given to them by their families, who gave £55,572 on average, Savills reports.

This has created a stark wealth divide between the children of people who were able to jump on to the property ladder in the 1980s and the less fortunate offspring of those who missed the boat.

Even though their parents were right-to-buy winners, it remains “a source of despair” for Claire Wilson and her brother that they sold the family flat for “just” £240,000 in 2000. They had tried to persuade their mother to hold on to the property and rent it out at the time. “She wouldn’t hear of it,” Wilson says.

Can’t buy, won’t buy

But if right-to-buy is such a good deal, why is the number of renters taking it up now so low?The first obvious answer is house prices: especially in London and the southeast, house prices have far outstripped incomes and the discount on offer is simply not large enough to make a difference.

Second, far fewer tenants in social housing are in work. “The scarcity of social housing means that these homes are now only given to the most vulnerable,” says Steve Partridge, the director of affordable housing at Savills. “Now people wouldn’t consider applying for a council house as a stepping stone to home ownership, because if they could afford to buy a council house they would never get allocated one.”

The social housing gap

Right-to-buy wasn’t just about creating a “property-owning democracy”. It was about reining in spending by cash-strapped councils. From the outset councils were only allowed to keep 20 per cent of the cash from these sales; the rest went to the Treasury. In 1989 an act of parliament forced councils to spend three quarters of that cash on paying down debt. This wiped out a lot of local authority debt, but it also limited how much they could borrow for capital expenditure, so they had no way of financing the building of new social housing.

The building of social housing largely fell to private developers. Privately owned housing associations now build most of the nation’s council housing; 79 per last year, compared with 14 per cent by local authorities. Most housing association tenants cannot buy their home through right-to-buy, unless it was previously owned by the council. There is an alternative right-to-acquire scheme for these tenants but the discounts on offer are much lower, ranging from £9,000 to £16,000.

England has suffered an average net loss of 24,000 social homes a year since 1991, primarily through right-to-buy sales and demolitions. Social homes were simply not replaced at anywhere near the rate at which they were being sold off. In the early 1950s councils built almost 200,000 homes a year. Last year they built only 2,780. The Bells Gardens Estate in Peckham, southeast London, was partly cleared two years ago to build 83 new homes, but they failed to materialise because Southwark council ran out of money to build them.

The building of new council homes on the Bells Gardens Estate in southeast London has stalled for lack of money

OLIVER CURRAN CONSTRUCTION

There are 1.2 million people on a council house waiting list in England, and 335,035 of them are in London. This is the highest figure in more than a decade and a 32 per cent increase since 2014. The average wait for a council house is more than five years in London, Slough, Aberdeen, Brighton, Oxford and East Lothian in Scotland, according to research from the Alan Boswell Group insurance brokerage. The longest average wait in the UK is 25.5 years, in Barking and Dagenham in east London, a figure dragged up by a severe shortage of family-size housing.

At the end of March this year there were a record 131,140 homeless families living in B&Bs, hotels and private rented housing while they waited for a social home, 12 per cent up on last year. Temporary housing cost the taxpayer £2.3billion in 2023-24, up 29 per cent on the previous year. Housing benefit is also soaring, up £9 billion, or 45 per cent, according to the government.

Fifty years ago 95 per cent of state spending on housing went towards building homes, and only 5 per cent on benefits, the Chartered Institute of Housing reports. By 2022 this ratio had flipped so that 88 per cent of the housing bill was spent on benefits and only 12 per cent on building homes.

Last year Lord Heseltine was asked by Anand Menon, the director of the think tank UK in a Changing Europe, whether the current housing crisis has its roots in right-to-buy. He admitted that it had led to a shortage of social housing but insisted this would not have happened if the Treasury had stuck to his original plan to allow councils to keep 75 per cent of the receipts to replace the council housing it sold. This never happened. Heseltine reiterated that he was still “totally committed to the idea of encouraging home ownership and tenants to buy their homes”.

The landlords step in

A significant portion of temporary housing is now found through third-party contractors who are paid to find privately owned properties to house the homeless. More often than not these are owned by private landlords who are looking for higher yields and fewer regulations than if they were renting to private tenants.

Saif Derzi, 33, is a Lincoln-based private landlord with 70 properties in his portfolio. Thirty of them are rented out to social tenants found and managed by a third-party contractor and the rent is reliably paid by the state. Many of the properties Derzi buys at auction are sold by cash-strapped councils who can’t afford to refurbish them. “I know one of the West Midlands councils sold off a load of their properties — three-bedroom semis — in shell condition that needed £30,000 to £50,000 spending on them,” he says. “They incentivised people to buy them by contributing a certain amount towards the renovation, then they leased it back from the private landlord on that basis.”

Private landlords such as Saif Derzi, centre, with his wife, Gina, and brother, Kas, are paid by councils to provide temporary homes for people on social housing waiting lists

MICHAEL POWELL

Life as a social-housing landlord isn’t always straightforward. Derzi has heard “horror stories” of properties being handed back with up to £30,000 worth of damage. They are usually housing people with complex health and social needs. But he recognises he is the beneficiary of some bad council business.

Wouldn’t it be cheaper just to build social housing? “Correct,” he says. “We’ve got to be honest about this; [councils] end up spending way more money paying third parties to find them housing.”

Repair and rebuild

Another reason Peter Walker, the former Tory environment minister, wanted to introduce right-to-buy in the mid-1970s was to transfer the costs of maintenance and repairs from local authorities to private residents. Today, estates that were built in the 1950s and 1960s are being left to crumble. Councils can’t afford to repair them and they can’t afford to buy back homes from right-to-buy owners either.

John Dickson, 62, was “thrilled” when he bought his two-bedroom flat at Arica House on the Slippers Estate in Bermondsey, south London, for £50,000 in 2012, when discounts were sky-high. A two-bedroom flat in the same building is now on sale for £300,000. “It was my only way of getting on the property ladder,” says Dickson, who was too ill to work when he was first allocated the flat but is now a civil servant. He lives with his partner, who is recently retired.

John Dickson, 62, bought his flat in south London through the policy but now faces a bill of up to £35,000 to pay for improvement works

VICKI COUCHMAN

He now faces an estimated bill of £35,000 to pay for improvement works in his block. Costs have soared because the “mismanaged” repairs overran by years and he is no longer in his five-year limited-liability period. “We’ve already paid £17,500 over a four-year period but that was an extra £384 a month we had to find,” Dickson says. “That was my little nest egg, and now we’re building another nest egg for the next bill to come in.”

Out of 88 flats on his estate, he believes 22 are privately owned. “But the majority of the owners don’t actually live here. They rent them out for between £1,600 and £1,800 a month,” Dickson says.

Southwark council says, “Major works programmes on our estates make sure housing for homeowners and tenants is kept up to a good standard. Under the terms of their leases leaseholders are responsible for a share of the works on their estates. It’s important leaseholders pay their share as otherwise the cost is borne by council tenants.”

In 2023 more than 3,000 council homes were demolished, an increase of 11 per cent in a year, because they were no longer habitable.

The search for a solution

In June’s spending review the chancellor, Rachel Reeves, threw £39 billion at the problem to fund the building of 300,000 new homes for low-income households, double the amount spent by the previous government. At least 60 per cent of this will be earmarked for council housing.

At the same time the housing secretary and deputy prime minister, Angela Rayner — who grew up on a council estate in Stockport, Greater Manchester — reduced the right-to-buy discount to just £16,000 for London, where housing waiting lists are longest, and up to £38,000 outside the capital in November 2024 “to protect much-needed social housing stock” from being sold off. She has been accused of hypocrisy. It’s politically difficult for Rayner to curb right-to-buy since she used the scheme to buy her own council house, in Stockport, in 2007, then sold it three years later for £48,500 more than she bought it for.

“It is hard to be anti right-to-buy sometimes without sounding as if you’re also anti home ownership,” says Steve Partridge of Savills. Last year he helped compile research for the Local Government Association that concluded it was “not fathomable for the scheme to exist in its current guise”.

Scotland abolished right-to-buy in 2014. Wales abolished the scheme in 2018 and housing association tenants haven’t been able to buy their home in Northern Ireland since 2022. Has right-to-buy run its course in England too?

“Personally, I wouldn’t abolish it,” Partridge says. “I would say that if you bought your house under right-to-buy and you sell it in the next 20 years, you have to sell it back to the council.”

Another idea, advocated by Alan Murie of Birmingham University, could be to let local authorities decide if they want to sell their housing like they used to before right-to-buy existed. But blocking the sale of council homes won’t solve anything, he adds, if we don’t also invest in building new ones.

Goldsmith Street in Norwich won the Stirling prize for architecture in 2019 — the only social housing to do so. Six tenants have applied to buy their homes there and two have been sold

ALAMY

Meanwhile, in Norwich, six council tenants have applied to buy their homes on Goldsmith Street. These sandy-coloured eco-friendly terraces, with wide streets and grassy play areas, were called a “modern masterpiece” when they won the Stirling prize for architecture in 2019 (the only social housing to do so).

Two properties have already been sold off at a 12 per cent discount for an average price of £215,425. The tenants, rightfully, were celebrating when they got the deeds.