Research is showing that highly processed foods can impact everything from our mood to our risk of cancer

Barely a day passes without another study warning of the dangers of ultra-processed foods (UPFs). The latest linked a high intake of UPFs to a 41 per cent increased risk of lung cancer compared to those with low intakes.

UPFs are defined as anything that contains additives not found in the home and is made to an industrial formulation. These types of foods, such as processed red meats, fizzy drinks, mass-produced bread, crisps, and sweets, now make up over half of the average Brit’s diet, and up to two-thirds in adolescents.

The lung cancer study found the risk rose after just 12 years of studying the participants. UPFs have also been linked with heart disease, diabetes and other cancers. But when do the risks kick in? Does an occasional pack of biscuits counteract a veg-based diet, or does it take years of heavy UPF intake to impact your health?

‘It’s important to take a balanced and informed view of UPFs,’ says Rhiannon Lambert, a nutritionist and author of Unprocessed Plate. She shares what happens to your body after eating UPFs for days, weeks, months, years and decades.

After a day – irritability, glucose spikes and cravings for more

Eating UPFs for just one day is unlikely to cause long-term harm, particularly within the context of an otherwise balanced diet. “While high consumption of UPFs can be linked to poorer health outcomes, occasional intake within a nutrient-dense diet is unlikely to pose significant harm. Rather than approaching this with fear, the more constructive response is to build awareness and gradually shift towards more whole and minimally processed foods wherever possible,” explains Lambert. “However, even short-term consumption may lead to noticeable effects on how the body feels and functions.”

UPFs tend to be high in refined carbohydrates and added sugars, while typically lacking fibre and essential micronutrients. As a result, they can cause rapid increases in blood glucose, followed by declines, which may contribute to temporary fatigue, irritability, and heightened food cravings, Lambert explains.

They’re also known to be high in fat, with one small Journal of Nutrition study finding a single high-fat meal increased blood pressure more than a low-fat meal.

But one of the clearest effects people experience when eating a UPF is their addictiveness. “These foods are engineered to be highly palatable and easy to consume in large quantities. Their soft textures and low fibre content reduce chewing time and slow satiety signals, which may lead to overeating and fullness or gastrointestinal discomfort,” says Lambert.

A 2023 study, published in the British Medical Journal, said UPFs including chocolate bars should be labelled and taxed as addictive substances, as they evoked “similar levels of dopamine in the brain to those seen with nicotine and alcohol.” The researchers also said people can get addicted to specific flavours and sweeteners added to UPFs.

UPFs are addictive, and seem to have similar effects on the brain as alcohol and nicotine, experts have warned (Getty)

UPFs are addictive, and seem to have similar effects on the brain as alcohol and nicotine, experts have warned (Getty)

If you typically eat your greens and grains, occasionally overeating a delicious brownie shouldn’t be a concern. “But these patterns can become more significant when repeated regularly,” adds Lambert.

After one month – weight gain and worsening gut health

The presenter and infectious diseases doctor Chris van Tulleken studied himself eating only UPFs for 30 days, reporting feeling as though he’d aged 10 years in just a month. His symptoms included poor sleep, heartburn, unhappy feelings, anxiety, sluggishness, and a low libido – and he gained almost 7kg (more than a stone).

In another, groundbreaking trial into UPFs at the US National Institutes of Health, 10 men and 10 women were fed either a high UPF diet or an unprocessed diet for 2 weeks. Even though the calories were the same in the meals they were fed, those on the UPF diet ate 500 more calories a day and, after two weeks, had gained 0.9kg on average. They concluded that UPFs “lead people to overeat calories”.

UPFs may also impact your gut microbiome, which can change in as little as 24 hours. “Several small studies suggest reduced microbial diversity and a lower abundance of beneficial bacteria with these foods,” says Lambert. “Certain additives found in UPFs, such as emulsifiers and some artificial sweeteners, have also been shown in preliminary studies to alter gut barrier function and microbiota composition. However, this evidence is still emerging, and further research is needed to confirm the mechanisms and long-term effects in humans.”

Beyond the gut, a UPF-heavy diet over several weeks may begin to influence mood, metabolic responses, and body composition.

Five swaps to reduce UPFs in your diet

Swap Warburton’s Protein Flatbreads for Crosta & Mollica Piandina Organic Wholeblend Italian Flatbreads

Don’t be fooled by the promise of added protein. Many flatbreads contain high amounts of preservatives and stabilisers to keep them pillowy soft.

Swap Tony’s Chocolony for Montezuma’s Dark Chocolate

Most chocolate is incredibly high in UPFs because of all the stabilisers. Dark chocolate tends to be much lower, however, and Montezuma’s is minimally processed.

The 74 per cent cocoa bar is minimally processed (Photo: Montezuma’s)

Heinz Tomato Soup for Daylesford Organic Slow Roast Tomato & Mascarpone Soup.

Tinned soups often contain acidity regulators, not to mention lots of sugar and salt. Opt for fresh, organic options when you can.

Swap Sun-Pat Smooth Peanut Butter for Biona Organic peanut butter

It’s the sneaky stabiliser (E471) in Sun-Pat that gives their peanut butter UPF status. Biona’s version contains nothing but nuts.

Swap Hellman’s Real Mayonnaise for Hunter & Gather’s Classic Olive Oil Mayonnaise

Lots of mayo contains extra additives and flavourings that aren’t strictly necessary. Look for ones with a shorter ingredient list.

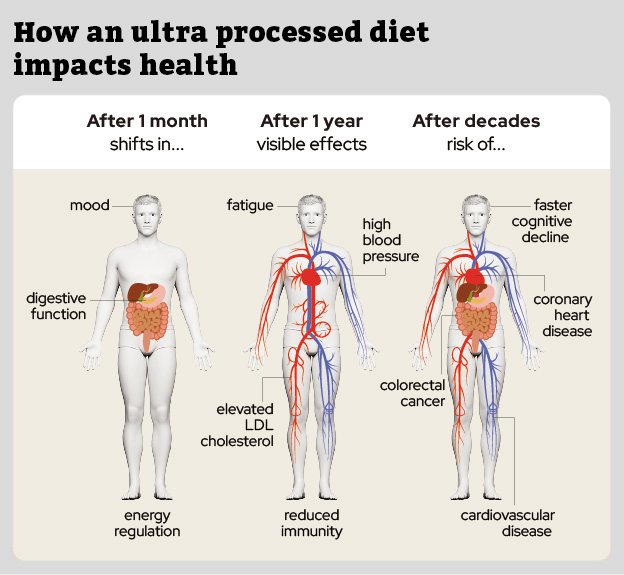

“Although significant metabolic changes are unlikely within a single month for healthy individuals, subtle shifts in energy regulation, digestive function, and mood are plausible when UPFs dominate the diet,” adds Lambert.

After a year – high cholesterol and blood pressure, poor immunity and concentration

“After a year of consistently high UPF intake, the body may begin to show more measurable and cumulative effects,” says Lambert. “Diets dominated by UPFs are strongly associated with an increased risk of insulin resistance, high blood pressure, and elevated LDL cholesterol, all of which are risk factors for cardiometabolic disease.”

Over time, a lack of nutritionally-dense foods can also contribute to micronutrient deficiencies, she warns, particularly in iron, magnesium, folate, and other B vitamins, which may lead to fatigue, reduced immunity, or impaired concentration.

The daily spikes in blood sugar and fats add up over the course of a year and could lead to prediabetes. Around a quarter of people with prediabetes develop type 2 diabetes within five years. A Spanish study that analysed the diets of 20,000 people, then followed up on participants’ health 12 months later, found that those with the highest intake of UPF consumption had a 53 per cent higher risk of new-onset type 2 diabetes within the year.

Dietitian Rhiannon Lambert says a highly processed diet can, over time, have serious effects on health, but it is possible to repair the damage (Photo: Frances Gizauskas)

Dietitian Rhiannon Lambert says a highly processed diet can, over time, have serious effects on health, but it is possible to repair the damage (Photo: Frances Gizauskas)

As for other side effects? “In terms of food additives, most substances used in food processing, such as emulsifiers, stabilisers, and artificial sweeteners, are metabolised by the liver and excreted by the kidneys or digestive system, and do not remain in the body,” says Lambert. “However, repeated exposure over time may still influence health. Some animal studies and early-stage human data suggest that certain additives may impair gut barrier integrity, contribute to low-grade intestinal inflammation, or alter the gut microbiota. These mechanisms may help explain some of the observed links between UPF-rich diets and chronic health conditions, but more research is needed to understand these effects in humans.”

After decades – rise in cancer risk, cognitive decline

The lung cancer study linked UPF and lung cancer risk after looking at data over 12 years, suggesting a decade of reliance can have huge health side effects. “Over a ten-year period, habitual consumption of UPFs has been associated with a significantly higher risk of chronic disease,” says Lambert.

For instance, a 10-year study found that those who sustained a high UPF intake had an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease. Plus, a literature review that looked at studies on more than 63 million participants who were followed for between two and 27 years found the risk of cardiovascular disease escalated with UPF intake, and cardio-cerebrovascular disease increased by 7 per cent with an UPF intake of up to one serving per day.

“In terms of cancer risk, processed meats – a common UPF – have been linked to an increased risk of colorectal cancer,” says Lambert. “A major UK study found a 32 per cent higher risk in people consuming around 80 grams of processed and red meat daily compared to those consuming under 11 grams.”

Other forms of UPFs, such as sugary beverages and ultra-processed snack foods, are being studied for potential links to breast, pancreatic, and liver cancers. “This is an active area of research, and while some associations have been observed, more high-quality studies are needed to determine causality,’ says Lambert.

Long-term intake of UPFs has also been linked to faster cognitive decline, with one Brazilian study showing a 25 per cent acceleration in decline among high-UPF consumers. “These risks are influenced by many factors, including genetics, physical activity, and other lifestyle habits, but the consistency of associations across multiple studies indicates that UPFs can play a role in long-term health outcomes.”

How to undo the damage

If you’ve spent years eating convenient foods rather than cooking from scratch, don’t panic. “The body has a remarkable capacity to adapt and repair, even after many years of less-than-ideal dietary patterns. Making positive changes to your eating habits today can support long-term health and reduce the risk of future disease,” says Lambert.

Eating whole foods, with plenty of fruit, vegetables, nuts and legumes, and cooking from scratch as much as possible is the simplest route to better health and gut health, she says. “One well-researched area is the gut microbiome, which can be supported through dietary diversity, particularly by increasing the variety of plant-based foods. Other effective strategies include preparing more meals at home using basic ingredients, even if that starts with just a couple of meals per week. Frozen and canned options can be convenient and affordable ways to include more whole foods. Physical activity, stress management, sleep, and hydration are all important in supporting recovery from previous poor eating habits.”