Play Landscape be-MINE / Carve + OMGEVING. Image Courtesy of Carve

Play Landscape be-MINE / Carve + OMGEVING. Image Courtesy of Carve

Share

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1032581/playgrounds-as-political-spaces-negotiating-risk-space-and-childhood

Playgrounds are spatial instruments through which society projects its expectations on childhood, testing the boundaries between control and autonomy, exposure and protection. They regulate how children relate to space, to others, and their bodies — encoding, often invisibly, social norms, fears, and aspirations. In this sense, playgrounds are not peripheral spaces of leisure; they are political constructs shaped by specific ideologies about what childhood is and how it should unfold. Since 1989, the right to play has been formally recognised in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, affirming that play is a fundamental part of human development. To design a playground is not only to draw lines on a plan or to install equipment in a park; it is to define the conditions under which play is permitted, imagined, or constrained.

Over the last century, playgrounds have become condensed arenas where larger tensions of public space play out. What began as experimental and open-ended environments — encouraging risk, invention, and informal appropriation — have often evolved into standardised zones of predictable use. Fenced boundaries, cushioned floors, and fixed equipment are not merely design decisions; they are material expressions of broader cultural shifts toward surveillance, liability, and normative behaviour. These transformations reflect a diminished trust in children’s agency and an increased desire to script their movements within the city.

Beatrix Park Playground / Carve. Image © Marleen Beek

Beatrix Park Playground / Carve. Image © Marleen Beek

Yet this trajectory is not linear, nor uncontested. Across different contexts, architects and designers have experimented with spatial strategies that reintroduce uncertainty, invite improvisation, and support forms of play that resist categorisation. From ambiguous topographies to flexible structures, these approaches suggest that architecture can expand rather than constrain the experience of childhood. In doing so, they open a broader reflection on freedom and control in the built environment, not only for children, but for all those who inhabit spaces shaped by design without participating in its decisions

Related Article Placemaking through Play: Designing for Urban Enjoyment A Short History of Risk and Freedom

The early history of playgrounds is inseparable from the history of modern cities. As industrialisation reshaped urban life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, concerns around public health, education, and juvenile behaviour began to influence urban planning. Playgrounds emerged not only as spaces for recreation but as instruments of social reform. In places like New York and Berlin, early playgrounds were introduced to discipline-free time, offering moral structure to working-class children who otherwise played in the streets. Supervised and enclosed, they were conceived less as spaces of autonomy than as tools of regulation within the emerging logic of the welfare state.

Jacques-Laurent Agasse, The Playground, 1830. Image via Wikipedia under Public Domain

Jacques-Laurent Agasse, The Playground, 1830. Image via Wikipedia under Public Domain

A different approach began to take shape in the postwar decades, particularly in Europe. Confronted with the devastation of cities and the need to rebuild both material and social structures, some architects and planners started to view children’s play not as a problem to be managed but as an opportunity for spatial and cultural experimentation. In Amsterdam, Aldo van Eyck created a dispersed network of playgrounds in the city’s vacant lots. These were minimal, abstract structures: metal hoops, sandpits, low platforms, concrete domes. Instead of imposing predefined uses, they invited children to invent new games, reconfigure relationships, and explore their own bodily limits. The playground, in van Eyck’s view, was not a container for play but a catalyst for imagination, civic interaction, and spatial learning.

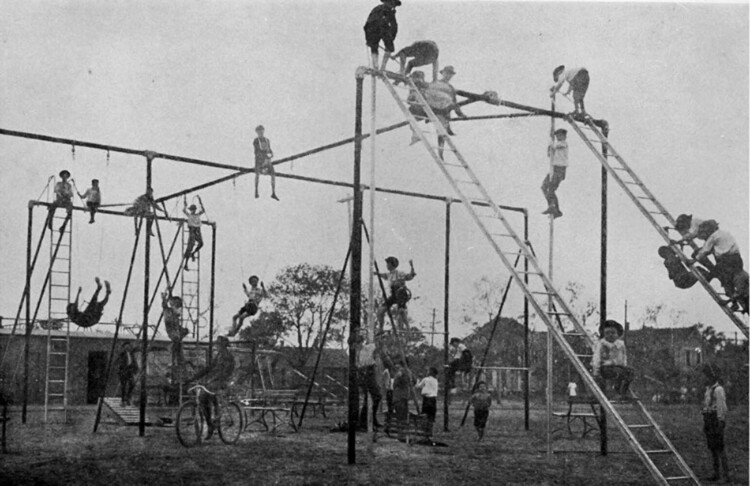

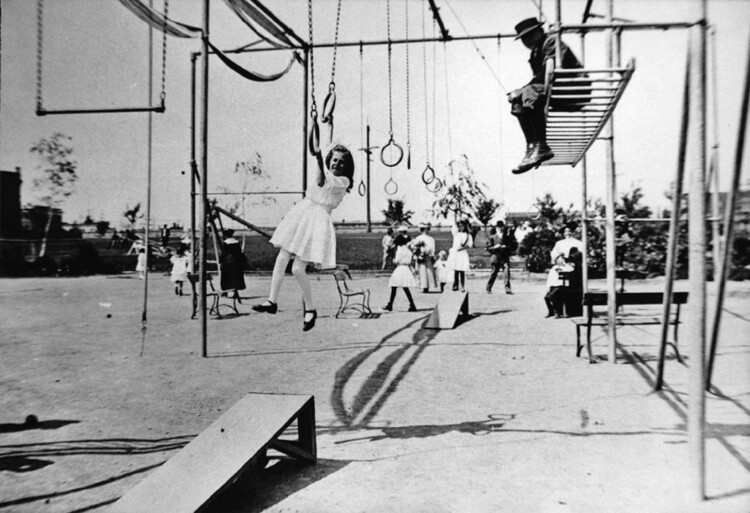

© Public Domain, Library of Congress, via Rare Historical Photos

© Public Domain, Library of Congress, via Rare Historical Photos

In parallel, the “adventure playground” movement offered an even more radical model. Originating in Denmark and expanding to the UK and Germany, these spaces were made from leftover materials — wood scraps, tires, ropes — and often included real tools. Children built and destroyed their structures under the supervision of “playworkers”, adults who intervened only when strictly necessary. These playgrounds embraced risk not as a danger to be eliminated, but as a necessary condition for growth, resilience, and independence. In doing so, they questioned adult control over children’s spatial experience and proposed a different understanding of design — one that prioritises process over form, agency over aesthetics.

Hiawatha Playground, 1912. Image © Public Domain, Library of Congress, via Rare Historical Photos

Hiawatha Playground, 1912. Image © Public Domain, Library of Congress, via Rare Historical Photos

An Adventure Playground is an area fenced off and set aside for children. Within its boundaries children can play freely, in their own way, in their own time. But what is special about an Adventure Playground is that here (and increasingly in contemporary urban society, only here) children can build and shape the environment according to their own creative vision. Harry Shier, Adventure Playgrounds: an introduction, 1984, National Playing Fields Association.

By the late 20th century, however, this experimental spirit began to decline. Concerns over safety, insurance, and legal responsibility led to stricter regulations and the standardisation of playground equipment. Prefabricated structures replaced improvised materials, and play became increasingly regulated through norms of compliance, visibility, and predictability. What had once been spaces of invention became zones of protection — visually bright but behaviorally narrow. This shift marked not only a change in how playgrounds looked and functioned, but in how childhood itself was conceptualised: no longer exploratory and autonomous, but vulnerable and in need of supervision.

Contemporary Design and the Politics of Control

In contemporary urban environments, playgrounds often sit at the intersection of well-meaning safety policies and highly regulated public design. The result is a widespread typology defined by repetition: standardised equipment, shock-absorbent surfaces, and fenced perimeters. These elements aim to minimise injury and ensure legibility, but they also reflect a deeper shift in how cities manage space. Rather than enabling exploration, many playgrounds reinforce a logic of containment, reducing play to a set of predefined actions: climb here, slide there, exit safely.

BLOX Playground / Carve. Image Courtesy of Jasper van der Schaaf

BLOX Playground / Carve. Image Courtesy of Jasper van der Schaaf

This model assumes not only a universal child but also a passive one; someone to be guided, protected, and monitored. Surveillance, both formal and informal, becomes a key aspect of spatial organisation. Visual exposure is privileged over spatial complexity, while ambiguity is treated as a liability. The architectural language of many playgrounds is therefore one of compliance: rounded edges, controlled access, bright colours, fixed narratives. Play becomes predictable, spatially scripted, and ultimately detached from the surrounding city

Yet this approach has not gone unchallenged. In recent decades, a number of architects and designers have developed projects that resist this flattening of experience. Dutch studio Carve, for instance, has produced a series of playgrounds that emphasise movement, tension, and uncertainty. Their interventions often blur boundaries between object and landscape, between equipment and terrain. Similarly, the play zones at Nishi Rokugo Park in Tokyo — built from recycled materials — transform discarded industrial parts into platforms for improvisation and self-directed play.

Marmara Forum Cloud Playground / Carve. Image © Asli Dayioglu

Marmara Forum Cloud Playground / Carve. Image © Asli Dayioglu

Other practices challenge the very distinction between playground and public space. The Bruit du Frigo’s ephemeral installations activate underused spaces with playful interventions that are temporal, participatory, and collectively imagined. Here, the absence of barriers invites coexistence between children and other users, fostering shared responsibility rather than spatial segregation. But what connects these examples is not a common formal language, but a shared resistance to the over-regulation of space. Rather than eliminating risk, they manage it through design; rather than scripting behaviour, they invite negotiation. In doing so, they acknowledge that play is not just a matter of physical activity, but of symbolic and social engagement — an encounter with difference, conflict, and transformation.

What Does It Mean to Design for Play?

Play is often romanticised as a natural, universal expression of childhood — spontaneous, imaginative, and free. In architectural discourse, it is commonly framed as something to be supported or enhanced, a behaviour that simply needs space, colour, or flexibility to unfold. But this understanding obscures the fact that play is neither neutral nor innocent. Play takes many forms — competitive, subversive, ritualistic, and solitary — and always operates within cultural codes and social structures. It is shaped by context, by material conditions, and by who is granted the freedom to play in the first place.

Beatrix Park Playground / Carve. Image © Marleen Beek

Beatrix Park Playground / Carve. Image © Marleen Beek

Article 31 / 1. States Parties recognize the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts. / 2. States Parties shall respect and promote the right of the child to participate fully in cultural and artistic life and shall encourage the provision of appropriate and equal opportunities for cultural, artistic, recreational and leisure activity. Convention on the Rights of the Child, United Nations, 1989

This ambiguity exposes the limits of architectural control, forcing a reconsideration of what it means to design for others. If play is an unstable, situated practice — often improvised, often resistant to purpose — how can it be drawn? How can it become a matter for design? The temptation is to translate it into gesture: to carve spaces that look playful, to introduce curves, bright colours, or unconventional forms. But aesthetics does not equal freedom. A visually dynamic space can still be prescriptive in use, while a banal structure might become a site of rich appropriation. The question is not how to design “fun,” but how to create conditions where the rules are open to negotiation — where play is not only permitted, but invented.

BLOX Playground / Carve. Image Courtesy of Lucas Beukers

BLOX Playground / Carve. Image Courtesy of Lucas Beukers

Architecture operates, by nature, through fixing things: positions, materials, functions, thresholds. Play, by contrast, unsettles. It ignores the program, misuses furniture, and crosses boundaries. This dissonance reveals a disciplinary paradox: the more architecture seeks to enable play, the more it risks formalising it. As Bernard Tschumi noted, architecture is not innocent — even spaces that claim openness carry ideological weight. A climbing net invites movement, but also defines direction and limits. A low wall may be subverted as a seat, but still reflects a logic of control. To draw space is to draw behaviour.

Some projects have tried to embrace this tension rather than resolve it. Noguchi’s Playscapes avoid typological clarity, offering neither furniture nor infrastructure, but sculptural suggestion. The Kolle 37 playground in Berlin continues the legacy of adventure play by allowing children to build their structures, negotiating not only form but responsibility. These environments don’t eliminate risk or uncertainty; they embed it. But even here, caution is needed. We should remind that openness does not automatically mean accessibility. The invitation to play is not experienced equally; it depends on confidence, on familiarity, on who feels entitled to occupy a space without instruction.

Piedmont Park Noguchi Playscape. Image © Waterfalls, Wally Gobetz via Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Piedmont Park Noguchi Playscape. Image © Waterfalls, Wally Gobetz via Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

This raises a broader point: design cannot guarantee inclusion, imagination, or empowerment. But it can acknowledge its limits. To design for play may be less about inserting playful forms than about resisting the over-coding of space. It may mean leaving gaps, allowing failure, designing elements that can be reconfigured or misunderstood. In this sense, the architect becomes less a composer of experiences and more a negotiator of thresholds — someone who holds space open rather than closes it down.

Reclaiming Play as Spatial Freedom

To rethink the playground is to reconsider the city. It is to confront how public space has become increasingly regulated, coded, and passive — designed more for circulation than for presence, more for control than for encounter. In this context, the playground functions as both a mirror and a provocation. It reveals how society imagines childhood, and by extension, how it manages autonomy, risk, and social difference. But it also offers a space to rehearse alternatives — to imagine spatial arrangements not bound by efficiency, productivity, or surveillance, but by the open-ended rhythms of play.

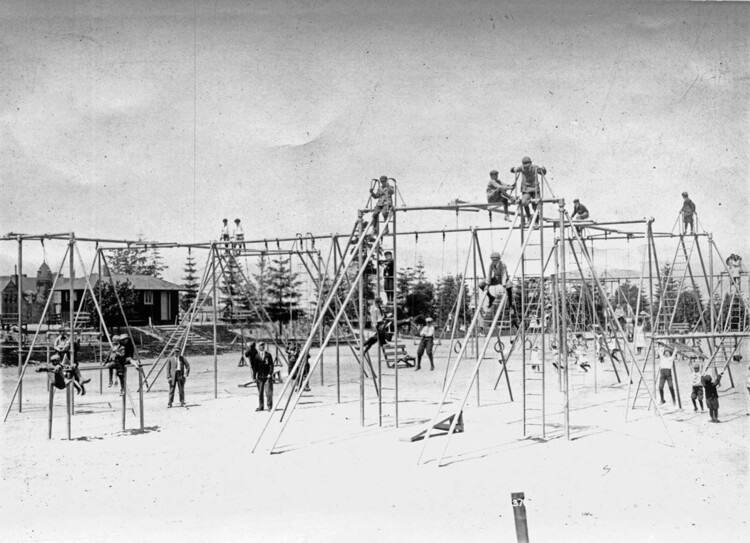

Broadway Playfield, 1910. Image © Public Domain, Library of Congress, via Rare Historical Photos

Broadway Playfield, 1910. Image © Public Domain, Library of Congress, via Rare Historical Photos

Reclaiming play is not just about play — it is about reclaiming space as a shared, negotiated, and plural condition. This does not mean turning the city into a theme park, or reducing architecture to affective gestures. It means treating play as a serious spatial question—one that challenges inherited models of authorship, functionality, and control. To engage with play is to engage with unpredictability, with conflict, with the possibility that space may be used otherwise. It is to recognise that not all behaviour needs to be anticipated, and that not all users require management. This demands a different architectural posture: less prescriptive, more propositional; less obsessed with form, more attuned to use.

Rings and poles, Bronx Park, New York. 1911. Image © Public Domain, Library of Congress, via Rare Historical Photos

Rings and poles, Bronx Park, New York. 1911. Image © Public Domain, Library of Congress, via Rare Historical Photos