I have remembered a cartoon that made me giggle. Henry VIII walks into a florist. On the counter is a sign advising customers to Say It with Flowers. So Henry says: “I’ll have a bunch of stalks.”

Which proves, I suppose, that saying it with flowers can be good for a laugh.

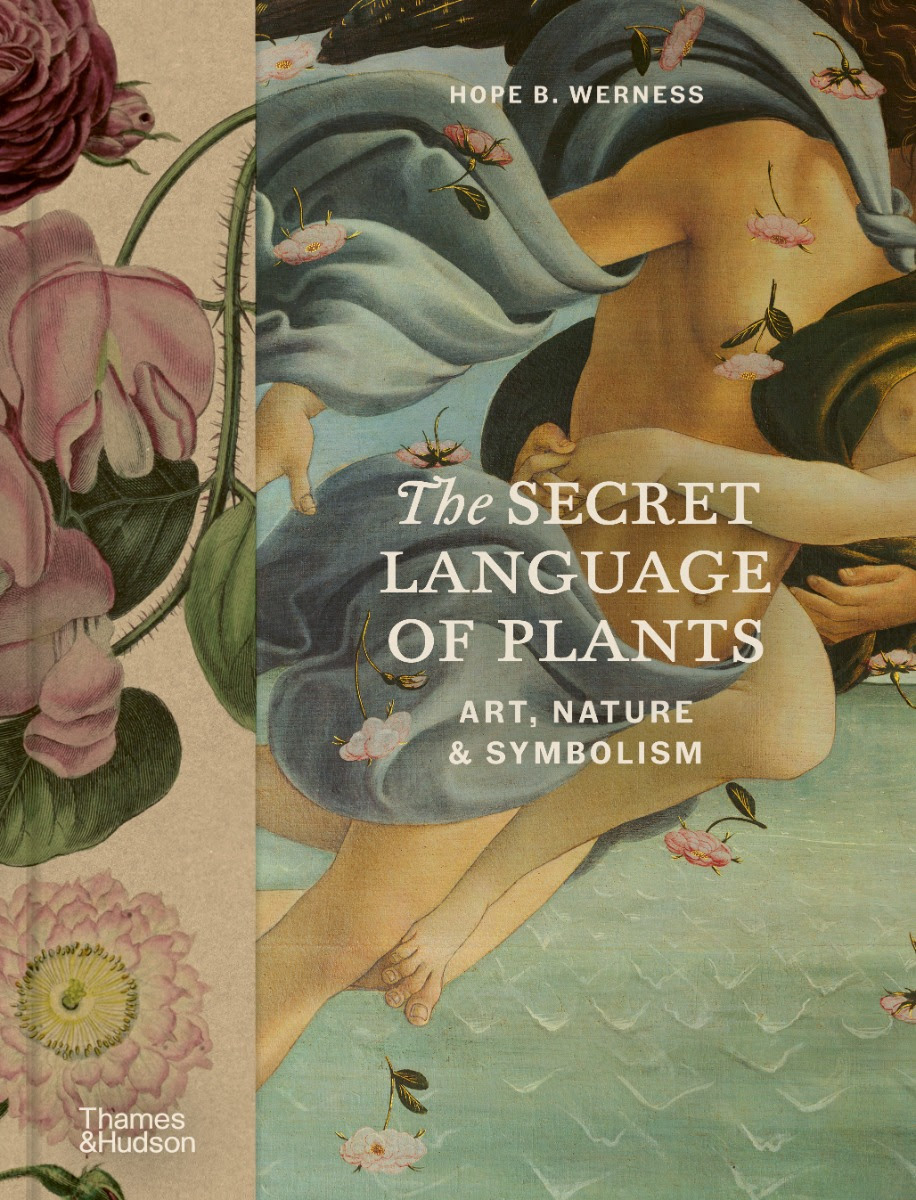

But, as Hope B Werness insists in The Secret Language of Plants, an encyclopaedic summer read packed with examples of horticulture’s insistent presence in art, the world of flowers can prompt a cornucopia of reactions and emotions. And humour is rarely the aim. Indeed, by the time you’ve finished reading this windy and heavily pictured tome you’ll be wondering how art might have symbolised anything profound, complex or important had it not had flowers, trees and vegetables at its (green) fingertips.

Van Gogh only features lightly in Werness’s bouquet, which surprised me. If I had written the book he would be on the cover. His Sunflowers and Irises convey the thump of ecstatic excitement that horticulture can hit you with more tangibly than any other painter. Except, perhaps, Renoir in one of his good spells.

But this thrilling directness can be deceptive. Flowers keep popping up in art because they are beautiful and stir the senses, but also because they have sneakier ambitions: the secret language Werness warns of in her title. And here the revelations are not always so sunny.

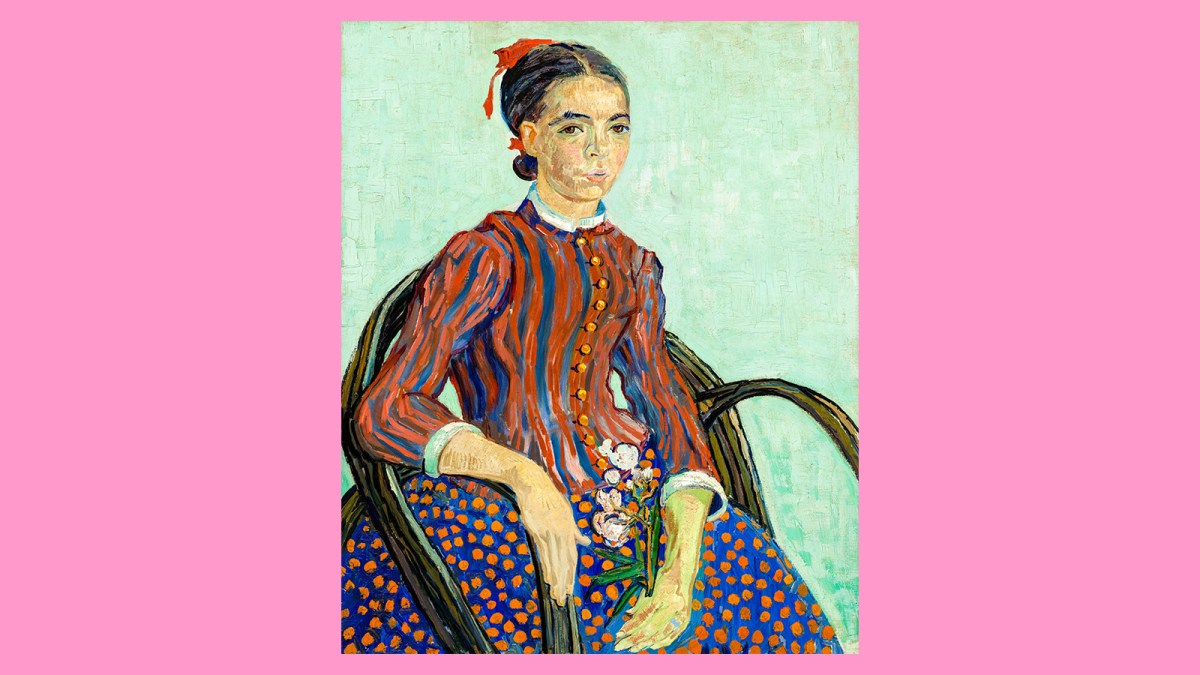

There’s a painting by Van Gogh called La Mousmé, which shows a young girl with a stern expression holding a sprig of oleander. It was inspired, we learn in one of Van Gogh’s letters to his brother, by Pierre Loti’s novel Madame Chrysanthème, which is set in Japan. “A mousmé,” Van Gogh writes, “is a Japanese girl — Provençal in this case — twelve to fourteen years old.”

• Henrietta Abel Smith — Britain’s new flower power painter

So far, so innocent. Until we turn to the flower she is holding. Oleander may be pretty but it is also deadly poisonous. Van Gogh had read about some French soldiers in the Peninsular War who had used skewers of oleander branches to grill their food. Eight out of 12 of them died. So when he puts a sprig of oleander in the hands of a teenage girl — “twelve to fourteen years old” — he’s issuing an uncomfortable warning. Danger ahead. The darkness of Van Gogh is rarely admitted to these days — the days of cuddly Vincent. But the secret language of plants can also be the secret language of uncomfortable truths.

Werness doesn’t deal with La Mousmé but she does deal with another awkward horticultural symbol — the palm. If you’ve ever stepped into a Christian church you may have noticed how many of the female saints gathered on the altar are holding palm fronds. Why? To symbolise their martyrdom. The brutal killing of young virgins, usually because they refused to marry a pagan, became a favourite theme in Catholic art.

Francisco de Zurbarán’s St Apollonia, 1636

ALAMY

The great Spanish baroque painter Francisco de Zurbarán produced a lengthy suite of depictions of these female martyrs, beautifully attired, stepping elegantly to their deaths, holding a palm. For the Romans the palm had been a symbol of victory. So when the female martyrs display one they are signalling their victory over death. Thus Zurbarán’s gorgeous St Apollonia in the Louvre clasps a palm in one hand and a pair of pincers in the other with a tooth in them. To torture her for her Christianity, the Romans, it was said, pulled out all her teeth. She is now the patron saint of dentists.

The bad news associated with plants does not figure vigorously in Werness’s book. It’s a summer tome, filled mostly with happy examples. So she omits an important stratum of plant life that has figured strongly in art: things that grow at the bottom of the forest. What fun painters have had with mushrooms, brambles and thistles. An entire arboretum of botanical art is devoted to the darkness under the trees.

Like tulips, it was a Dutch speciality. Van Gogh produced his own versions of the “sous bois”, as it was called, but the heyday of the genre was the 17th century when artists such as Rachel Ruysch and Otto Marseus van Schrieck haunted the woods at twilight looking for vegetation that would remind us of the brevity of life and the nearness of the end.

Otto Marseus van Schrieck’s Still Life with Mushrooms and Butterflies

BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

In a typical Ruysch or Van Schrieck, a writhing bramble or broken mushroom will be surrounded by lizards, snails and snakes. In God’s glorious kingdom, everything had its place, and the stuff at the bottom of the woods was the stuff that was most regrettable. The denizens of the dark represented the sinfulness that lurks at the base of humanity. Occasionally, an innocent butterfly would flutter down to compare its briefly joyous life with the eternal gloom of human guilt. Among the mushrooms, however, its days were numbered.

• Read more art reviews, guides and interviews

But enough of this gloomy horticulture. In most cases, plants do not appear in art to remind us how short life is. The messaging is usually more hopeful and certainly more varied. Take the fabulous 17th-century painter Bartolomeo Bimbi, who worked for the Medici family in Florence and whose speciality was lemons.

Lemons were a big deal symbolically in 17th-century art. Exotic and costly, they did not rot and maintained their bright colour for lengthy stretches — until you peeled them. So most of the lemons in baroque art are warning us of the big peel ahead.

Bartolomeo Bimbi’s Citrus

AKG-IMAGES

Bimbi, though, was employed by the Medicis to record the different species cultivated in their specially built lemon houses. His art, with its huge assortments of heaving citrus fruit, is both a spectacular record of the many varieties and a celebration of the uplift that horticulture brings into our lives.

So if I walk into a florist with a “Say It with Plants” sign on the desk, I’ll be demanding: “Give me some Bimbi!”

The Secret Language of Plants: Art, Nature & Symbolism by Hope B Werness (Thames & Hudson £25 pp240). Buy from timesbookshop.co.uk or call 020 3176 2935. Discount for Times+ members