When looking for their next book recommendations, Sylvana, 19, and Ellie, 12, don’t tend to browse their local library or bookstore.

“If I want to get a certain book, I … just look it up on TikTok,” Sylvana says.

“I’ll be like, ‘Oh, what’s the best book to read?’

“We have found a lot of books that we have gotten into from, like, YouTube,” Ellie says.

Sylvana and Ellie use TikTok and YouTube for book recommendations. (ABC: Carl Saville)

However, Sylvana says the recommendations on these platforms aren’t always spot on.

“I know my little sister, she was reading some books that she shouldn’t have been.”

The growing influence of BookTok, BookTube, and Bookstagram has a researcher concerned about the content young people are engaging with, and they are calling for an industry-wide book rating classification system.

Emma Hussey researched 20 books popular on BookTok and found 65 per cent depicted domestic violence. (Supplied: Emma Hussey)

“It really is about, ‘Don’t judge a book by its cover,'” says Emma Hussey, a digital criminologist and child safeguarding expert at the Australian Catholic University’s Institute of Child Protection Studies.

“Just because there are cartoons on the front, [it] doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s going to be developmentally appropriate for a 12 to 17-year-old,” she says.

Domestic violence themes

Dr Hussey’s latest research looked at 20 books that are popular on BookTok, analysing them for domestic violence behaviours, other violence, including torture, murder and destruction of property, and sexually explicit scenes.

“Of those books, 65 per cent of them had these domestic violence adjacent behaviours on the page,” she says.

“The themes that we were seeing were things like manipulation, intimidation, physical restraint, dubious consent, stalking.

“At one point, there was a GPS tracker used … we know that technology-facilitated domestic violence is on the increase.

“I think, more so than not, you’ll find degradation and put-downs littered throughout also.”

Loading…

The algorithm on these platforms is another concern for Dr Hussey, as she says it is often based on popularity rather than reader safety, so it will sometimes push adult fiction towards young adult, or YA, readers.

Young adult fiction is a category of its own in publishing and is generally aimed at readers between the ages of 12 and 18.

“I know that there’s a system that authors use to know whether their books are marketed to a younger young adult audience or an older young adult audience [but] that’s not made explicit or clear in bookstores or libraries,” Dr Hussey says.

Children’s book specialist Tracy Glover, a bookseller in Adelaide, says she has noticed a shift in the reading habits of young people since the rise of social media.

Tracy Glover says many bookstores have age recommendations on a lot of young adult fiction. (BTN High: Cale Matthews)

“The … students from the local schools, often when they come in, they come in with a specific request,” Ms Glover says.

“It might be something they’ve talked about or someone’s mentioned at school; it might be something that’s very current on Netflix or TikTok.

“It’s a very powerful medium when it comes to book sales.”

In saying this, Ms Glover also believes the young adult collection is clearly labelled, at least in the store she works in, which helps guide young people to age-appropriate texts.

“We have a fairly clear boundary just by geographically where the [young adult] books are.”

Young adult fiction is aimed at readers aged between 12 and 18. (BTN High)

Additionally, Ms Glover says her bookstore, like many, has age recommendations on a lot of its YA fiction.

These recommendations are guided by staff discretion and databases such as Common Sense Media, which are designed with young people’s reading and safety in mind.

“It’s very rare that we have to say to a reader, ‘We’re just not sure that’s going to be suitable for your age level,’ but if we felt strongly enough, we would just give that warning,” she says.

“The 12 to 14-year-olds, we’re very mindful with what they choose and what we would recommend for them.

“Once they hit about 15, then it is their decision. They’re probably … exposed to a lot of those things already, if not in literature in, often, sadly, what they’re watching.”

Censorship concerns

As someone who spends a lot of time in bookstores, Faith, 21, says it’s easy to identify which areas are dedicated to YA fiction, and she is concerned about the impact age classifications could have on information.

Faith has reservations about the idea of a book classification system. (ABC: Carl Saville)

“Hard ratings like, ‘You can’t read this until you’re ‘X’ age,’ I think that’s limiting people being able to share ideas with each other,” she says.

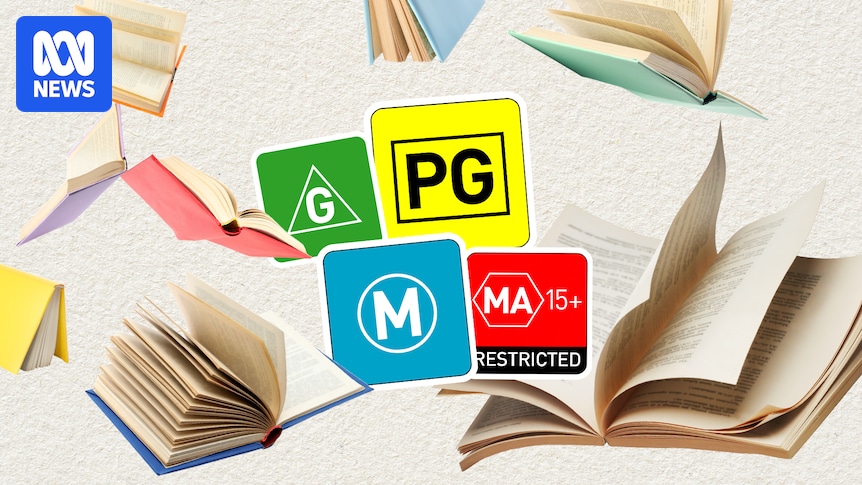

As far as what a classification system might look like in practice, Dr Hussey says we don’t have to look far to find models that already exist.

“We have implemented these sorts of classification systems across streaming websites, across movies that you purchase in store, so it’s not a new system,” she says.

“It’s just about bringing that to this new medium that we’ve not previously considered before.”

Young adult author Will Kostakis says the way we experience books is fundamentally different from other media, so taking a classification system built for films or video games and applying it to books wouldn’t work.

Will Kostakis does not support age classifications for books. (BTN High: Joseph Baronio)

“The thing about books is you can actually go into the emotions of an action — you have a character’s thoughts throughout,” he says.

“You would have the character reckoning with consequences afterwards, thinking about it, living in it.

“I’m against this classification system.”

Owen, 18, agrees that books sit in a category of their own.

Owen is concerned age classifications for books could lead to censorship. (ABC: Carl Saville)

“Movies are a bit different because, obviously, you’re watching it play out; reading, it’s your imagination and you can just close the book if it’s too much for you.”

The idea of classification also raises questions around censorship.

“I think it stretches to a level of potential censorship, whether it be unintentional or not,” Owen says.

“With films, you have to pay to get it tested and see whether or not it’s appropriate or not.

“I think for like young independent authors, that might stop them from being able to publish their books … I don’t think that’s a great thing either.”

Subscribe to the BTN Newsletter

Mr Kostakis shares similar concerns, particularly around who determines how texts are classified.

“Would it be parents? Would it be politicians? Would it be booksellers? Would it be, you know, publishers?” he says.

“The thing is, publishers and booksellers already choose and engaged parents already choose — they are talking to their kids.

“We already have rules in place to protect kids, but that can be exploited, and so when we talk about classifications, I’m always worried about not just the next step, but the step four points down the road.

“A lot of the authors that I’ve been talking to and librarians, the big thing they worry about is censorship.”

Dr Hussey insists this isn’t about sanitising literature, but more about increasing awareness.

Malaysia’s ‘moral’ crackdown on books

“This is not about banning,” she says.

“Censorship is about the denial of access, the stopping of access.

“This [classification system] does not push or advocate for the removal of access to content.

“It’s more about giving respect to young adult readers, flagging content that may not be developmentally appropriate for them at that stage, or they may not be ready for.”

Ms Glover believes more focus should instead be placed on educating readers.

“There has to be some responsibility taken from the reader themselves and then from their support system,” she says.

Mr Kostakis agrees and says we should expect more from our readers.

“I grew up in the era of Twilight, all the teen girls in my life weren’t like, ‘Wow, I can’t wait for a 108-year-old who’s posing as a teenager to sweep me off my feet,'” he says.

“They are getting the feels and all of the tropes and being like, ‘Cool. This is a bit romantic. This is a bit spicy,’ but I don’t think they’re looking at these books as manuals on how to live their romantic lives.”

For Ben, 20, any form of age classification implies that some topics are inherently inappropriate for kids, which he disagrees with.

Ben says it’s important kids have access to books that reflect the reality of their lives. (ABC: Carl Saville)

Instead, he thinks young people should be able to access books that reflect the realities of their day-to-day.

“When I was like 15, 16, there [weren’t] any books that I felt like the content would be super different from what you just experienced in like your daily life.

“You’re becoming an adult, so you should be exposed to like everything.”