Jack Murray chats to frontman Murray Matravers of indie-pop band hard life about mounting pressure, jet-setting around the world and the importance of pressing pause whilst unravelling the layers of the new album, Onion, out now.

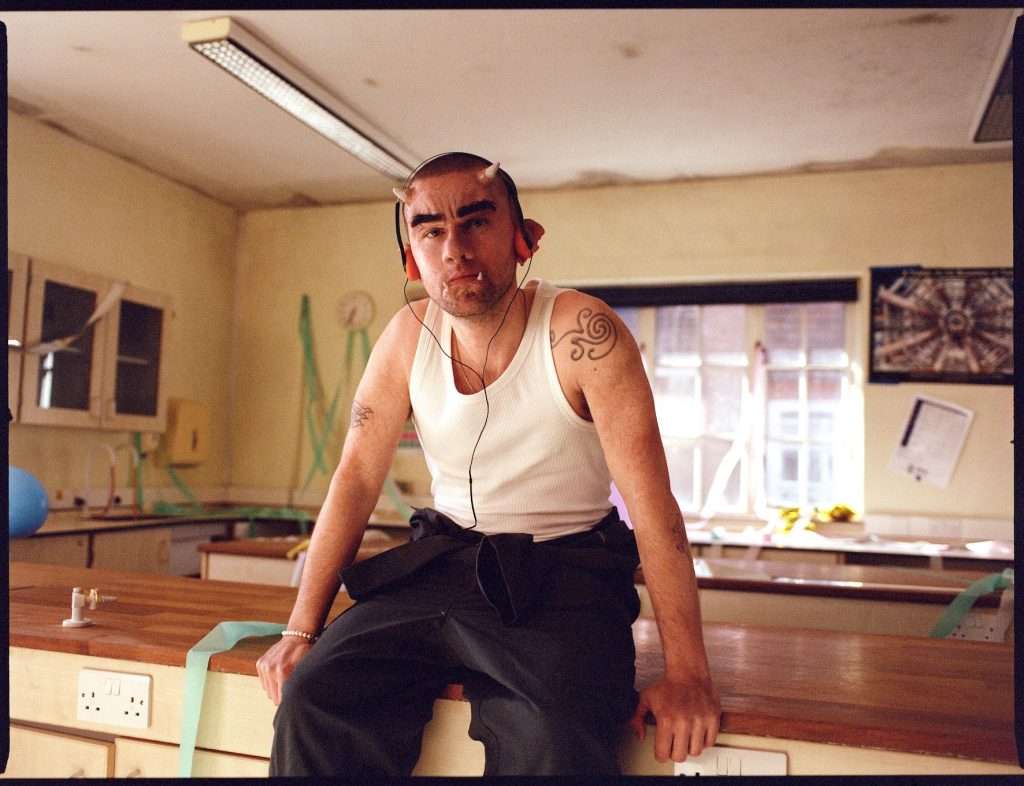

It hasn’t been an easy life for Murray Matravers and Co over the past few years, yet the band’s public legal fallout with EasyJet over usage of the “easy life” name and ensuing switch to “hard life” must’ve felt like an even bigger record scratch when considering their early successes. Emerging from the streets of Leicester in 2017 with the smash-hit “Pockets” (as featured on FIFA!) and quickly known for their breezy synths and energetic beats perfect for a summer’s day – you’d have been forgiven for thinking they had everything planned out after a line of well-received EP’s led to two albums in the form of 2021’s Life’s a Beach and 2022’s Maybe In Another Life. However, the stress of relentless writing and touring turnarounds seems to have enacted a price to pay for success, and speaking from a relatively plain white living room, Matravers seems like he’s came and been through the other side.

I’ve personally followed the band for some time now, since well before that first album, having seen them a handful of times as they ventured north of the border. It was during their last Scottish show that sparked alarm bells as a drink spilled on one of the synthesizers backstage, causing most of the band to briefly leave as the issue was fixed. Matravers remained however, with a flight of Scottish whiskies and a hyped-up crowd to entertain. The show was curtailed not long afterwards, and whilst I’m not one to dig up old hard feelings, the ensuing radio silence felt like a retrospective flashpoint that the later lawsuit only built upon.

If you believe Shrek, and onions have layers, then so too does this album as it addresses the spaces in-between the past few years and what goes on during the gaps. As Matravers likens himself to the lovable Scottish ogre during the aptly-named track ‘OGRE’, it’d seem he has layers too, which we began to unravel whilst chatting through the production of the new record, and what’s changed through striking a balance between taking it easy and hard.

JM: So, the court battle with EasyJet has been pretty well-documented, but beyond the strife of the lawsuit, did it present a bit of a reset button for approaching songwriting?

MM: Yeah, totally. Absolutely, man. I think so much of our career, [had] just been like relentless, and we’d never stop touring. I love touring, don’t get me wrong, but it’s incredibly difficult; physically and mentally, and this was something that we were thrown into. It never really stopped. With everything that went down with the court case, it pressed pause on everything.

I suppose all of us in the band re-evaluated what it is that we wanted. Did we arrive in the place that we intended? Were we exactly where we were meant to be? Is this the kind of thing we want to do? For me as a writer, I suppose for the first time I had time on my hands again. I’d been writing in-between tours and trying my best to stay as prolific as possible. But all of a sudden, I had this abundance of time and also the gift of so much that I wanted to say – those two things were like the perfect storm.

When I went away to write this record it just came so easily for me, I actually wrote the whole thing in a month. Oftentimes in my previous iterations of writing it’d taken me years to make some of my albums, you know, and this one just… it just appeared to me one day and it was there, the easiest thing I’ve ever made.

JM: Also well-documented is the production process for the new album, which involved a studio called Onion in Japan and Taka Perry as a producer (who you’ve became quite close with). Do you therefore see songs as attached to certain places or has it all become a bit unmoored after leaving the bounds of Leicester?

MM: What I did differently on this album is I made the whole thing in one place with one person. Even my first album was made all over the world – I was back and forth to L.A when I first signed my record deal. I was working with all manner of different producers, and you get thrown into all these sessions [which] can be very disorientating as a young artist whose [hardly] even left Leicester before. I’d been to Scotland a bunch of times!

I was all over the world all of a sudden and it was very disorientating. Fair enough, I made this album on the other side of the world too, but it was in one location and that location very quickly felt very comforting, like home and the place where I could be very honest. Taka was a person who I felt very close to instantly. The second we met we’d so much in common that [on] this album, I could just be so raw and so real and so vulnerable, and I didn’t feel scared ever in the process. Had I been like flying around, meeting new people, working with different people, I think maybe I would’ve made something slightly more, potentially, like more commercial or whatever, but I don’t think I would’ve been happy with it.

And I can’t repeat this process, you know, I can’t ring Taka up and be like: “right, let’s go to Onion for a month and make another album.” It won’t be the same. It won’t work. We’ve even actually tried that [since]. We’ve been to the Japanese Alps. We’ve been to Onion; we’ve done all these things. Each of those places really does inform the sound of the record. I couldn’t have done this anywhere else.

JM: It certainly sounds like the logistics of being in Japan shapes the sound the album takes, how involved were the rest of the band in making the record? Was it purely logistical, or is the way you make music shifting?

MM: It’s funny because I’m being asked that quite a lot. But ever since our first song, “pockets”, like I’d always done all the writing. Our first album, I did all the writing then and the second album and all the mix tapes in-between.

So actually, nothing has changed. The band have always been more like a live band than a recording band, and I’ve often played most of the instruments on all of our records. On this particular album, Taka played nearly all the instruments because we would work so quickly. We’d be talking, we’d have something to say, and I’d be on my laptop just writing and writing and writing and writing. An hour later, I’d [have] written all like this whole massive block of unedited lyrics. He would’ve made the entire instrumental and produced like the whole thing ’cause he’s genius. And then we’d be like, right, “let’s collaborate”. But this did mean he played most of the music on the album, and he’s great!

JM: I suppose one exception to that would be “are you sti11 watching??” which is a bit reminiscent of “Bubble Wrap” [from the last album, “Maybe In Another Life”] in terms of revolving around a pivotal voice-note [from] during production. Do you think that informs a wider journey that Onion seems to take?

MM: Yeah, so “are you sti11 watching??” is a conversation between me and Taka. We’d been in the studio so much, and something that I don’t think artists talk about enough is like making art (musical or otherwise) does take an enormous amount of energy.

It puts a toll, certainly for me [pauses… because] I drink a lot, when I’m creative. It helps unlock a certain part of me which I otherwise find unreachable, y’know? But I don’t sleep much and it’s a physical process which is incredibly draining, and me and Taka were going through that simultaneously. This conversation you hear is me and him talking about how the process is going. I’m like “dude, where you at? I’m giving it my all.”, and he’s like “so am I man, you need to work some [stuff] out.”.

I wanted to include that conversation because it’s testimony to the fact that these things don’t just happen, they take a commitment from (in this case) two people, to want to make something from start to finish. It’s not an easy process and that’s why I’m so proud of every time I’ve been able to do it, like “damn that was crazy”; and then I go teetotal to sort my life and my body out for a bit afterwards.

JM: I was swaying on whether to mention this, but I happened to be there during the band’s last trip to Glasgow. Sometimes things happen, though I wanted to ask, was there an inherent amount of pressure after the success of Maybe In Another Life that presented itself even before the lawsuit, leading to that?

MM: I think there’s always been pressure. We were lucky enough, since the first thing we released actually, garnered fairly mainstream commercial success and there’s always been the pressure to maintain that. I suppose the only thing that’s changed is my ability to deal with that pressure and ignore it. Particularly on this record, if I was feeling the pressure there’s no way I would’ve made it in a month and not edited it or mixed it. I would’ve been like: “okay, that’s the basis of it. now let’s make it perfect and re-record, make it perfect, blah blah blah…”.

I don’t feel that pressure anymore. In Glasgow, I felt an enormous amount of pressure to entertain people and have done my whole life. That’s some deep-seated insecurity of mine but that night, the stage went black, everything fucked up, and in my ears our team were like: “look, you’re going to have to come off stage for 15 minutes and just let the crowd wait till we sort it.” – that wasn’t okay for me, people had paid to be there. I think for me throughout these experiences substances have always been a crutch for me, and something that have helped me get on stage in the first place – clearly that night I took it too far. I apologise because you paid money to see me and didn’t get to hear the songs that you like.

JM: In contrast, I caught your Big Weekend set as well and one of the big takeaways was how different that felt, everyone seemed excited to be up there. Was getting back up on stage an easy thing to do?

MM: Interesting man. I suppose so much has changed but one thing that has fundamentally changed in our project is our attitude towards the opportunities we get. By that I mean we’ve gigged so much that all of a sudden, every gig [wasn’t] very important, and it [didn’t] matter if it was a huge TV show or a big headline festival set. [But] all of a sudden now it’s like I know as facts any gig we play now could be our last gig. I don’t think that’s hyperbole, y’know? We were in a position where we were doing the most and overnight that stopped, and that can be the reality again.

What’s happened in our band now is whenever we step on that stage, we’re just so present and so in the moment in a way that you really couldn’t synthesize and that really is the truth – we’re there and we’re gonna make it the best show of our lives every single night. That’s changed our attitude towards touring because it was a real difficult thing for all of us and now it’s something we’re all incredibly grateful to do.

JM: Do you think there was a silver lining to the break then – did it feel like a break?

MM: Absolutely. I think there’s been so many silver linings, the biggest one is don’t take anything for granted. It’s so cliched, but I think old people like me always tend to say that! Once you realise that it’s not a given… I think there was a problem man – we had such incredible luck, so early on, oftentimes people ask me: “how did you do it?” and I can try and articulate it, but so much of it was luck.

Now I’m just incredibly grateful for that luck because I realise that you can have bad luck, and things can go the complete opposite way. I think you’ve got to remember that if things are going your way, just be grateful for that – if you’re getting booked for Radio 1 Big Weekend you better play the best show of your life because you’re blessed to be there! I think a younger me was like “I’ll be there next year – I don’t give a shit.”. It’s naivety, thinking you’re gonna live forever. You’re not, especially in music man. You could be gone tomorrow, so let’s go.

JM: Speaking of, “end credits” finishes the album on a hopeful yet uncertain note. What’s the plan for hard life after this? You’ve pointed to the idea of it being very uncertain – each show potentially being your last.

MM: I think one thing that this whole [situation] has taught me, and working in music in general has taught me this – there’s not really much point in having a plan. I haven’t been able to execute a single plan I’ve ever made in my whole life! I could not imagine any of this happening. So I don’t really have much of a plan, man.

I want to continue making music, and if there’s a reality in which I can continue doing that then I’m doing it. [But] I dunno, I think I really just fly by the seat of my pants at this stage.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity. A special thanks to Warren from Chuff Media.