Key Points

- US tax policy is a significant reason for the near-total absence of airport privatization in the US. The only privatized US commercial airport is San Juan’s Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport.

- Two tax law changes that could make airport privatization more attractive to US airport owners are removing the requirement that tax-exempt airport bonds must be paid off before there is a change in airport control and expanding the scope of successful surface transportation tax-exempt private activity bonds to include airports.

- These reforms were suggested in several government agency reports and were highlighted in a 2018 infrastructure investment report by the first Trump administration—indicating that the current administration may be favorable to these tax policy changes.

Executive Summary

While the United States has mostly private utilities and has had several decades of long-term public-private partnerships (P3s) in highways and transit, all but one of its commercial airports are government owned. By contrast, as independent researchers have identified the benefits of airport privatization—such as significantly better performance—governments in Australia, Europe, Latin America, and portions of Asia have privatized large fractions of their commercial airports, via either outright sale or long-term P3 leases.

Congress has enacted several versions of a law to permit government airport owners to enter into long-term P3 leases of their airports. To date, only San Juan, Puerto Rico, has entered into such a lease, although planned leases of Chicago Midway and St. Louis Lambert attracted significant investor interest.

Several federal bodies have looked into why airport privatization has not caught on in the United States. Airline opposition is no longer a significant factor, with airline-friendly lease terms worked out for the three cases noted above. The policy that could most likely open the US airport privatization market appears to be tax changes to put US airport financing on a level playing field with countries where airport privatization and P3s are widely used.

This report explores two tax law changes. One would remove the requirement that tax-exempt airport bonds must be paid off before there is a change in control, such as a long-term lease. The other would expand the scope of successful surface transportation tax-exempt private activity bonds (PABs) to include airports and other transportation infrastructure.

These changes would enable airport owners to receive an amount closer to their airport’s gross value, rather than the net value after paying off the outstanding tax-exempt bonds. Data in this report show that long-term P3 leases could yield windfalls for the owners of many large and medium hub airports. In some cases, the airport owner’s proceeds could be enough to pay off a large portion or all of the jurisdiction’s unfunded public employee pension liability. The proceeds could also go toward needed but unfunded infrastructure projects or reduce other indebtedness.

Introduction

Over the past three decades, airports in many developed countries have been privatized, via either sale to investors or long-term leases generally referred to as public-private partnerships (P3s). Data from Airports Council International (ACI) before the pandemic found that in Europe, 75 percent of passengers used privatized airports. Similar figures were found for passengers in Latin America (66 percent) and the Asia-Pacific (47 percent). By comparison, only 1 percent of passengers in North America use privatized airports.1 The only privatized US commercial airport is San Juan’s Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport, which was leased as a P3 in 2013.2

With more than 400 airports worldwide either sold or long-term leased to investors, researchers now have enough data to analyze privatized airports’ performance compared with traditional government-owned, government-operated airports. The largest of these studies, a 2023 working paper by Sabrina T. Howell et al., found many benefits at airports where the investors included infrastructure investment funds, which operate airports as real businesses.3 The changes include

- More airlines, serving a larger number of destinations;

- Lower average airfares due to increased competition, including from low-cost carriers;

- Increased airport productivity; and

- Greater passenger satisfaction, as measured by ACI’s annual Airport Service Quality survey.

One factor in these improvements is the rise in airport groups (such as Aeroports de Paris, Aena Aeropuertos, Fraport, VINCI Airports, and Flughafen Zurich). By managing multiple airports, such airport groups benefit from economies of scale, standardized practices, and a pipeline of experienced managers who can move up to larger airports.4

Congress has encouraged US airport privatization since enacting an Airport Privatization Pilot Program (APPP) in 1996, which allowed up to five airports to be leased as a P3. That program was expanded to 10 airports in 2012. Most recently, in the 2018 Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) reauthorization legislation, Congress replaced the APPP with broader legislation, the Airport Investment Partnership Program (AIPP). It opened the program to all US commercial airports, reduced other restrictions, and for the first time allowed the proceeds from an airport P3 lease to be used for general government purposes by the airport owner (rather than being restricted to investments in airport improvements).

Yet since that landmark legislation, not a single US airport has been leased as a P3, though several have tried. St. Louis in 2019 offered a long-term P3 lease of Lambert International Airport. Eighteen international teams responded, and the highest-ranked dozen made detailed in-person presentations to the city government and its advisers. In addition, the airlines serving the airport developed a pro forma agreement with the airport. But the mayor terminated the process due to regional political opposition.

This report explores a possible way to make US airport privatization more attractive to airport owners by proposing a level financial playing field for potential private-sector airport investors, similar to what already exists for US surface transportation P3 infrastructure. Those changes would lead to larger upfront lease payments, in addition to the performance improvements that Howell et al. noted.

Why Aren’t More Airports Privatized in the United States?

The relative lack of US airport privatization has puzzled researchers for the past two decades. The Airport Cooperative Research Program (ACRP), sponsored by the FAA and administered by the National Academies’ Transportation Research Board, released a detailed report in 2012, after Chicago failed to lease the Midway International Airport under the APPP.5

The ACRP study cited a number of reasons airport owners favor the status quo:

- Airports have been historically owned by government entities.

- Airport owners want to keep their control.

- More federal grants are available to government-owned airports.

- Airports can continue collecting passenger facility charges (PFCs).

- Financing airports is low-cost because it is tax-exempt.

- Airports are exempt from federal and local property taxes.

- To obtain federal grants, airports must adhere to FAA grant assurances and operate in accordance with its safety guidelines.

- Any privatization proceeds would continue to be used for airport purposes only.

- Changing ownership could force airports to repay their federal airport grants.

- Airlines might veto privatization.

- If they privatize, airports could face opposition from members of collective bargaining agreements and public-sector unions.

An appendix to that study noted that for two Midway Airport P3 lease attempts (in 2005–09), the city had overcome factors one, two, six, 10, and 11, but the initial deal fell through when the winning bidder could not obtain financing for its $2.5 billion offer for a 99-year lease. Support from principal Midway airlines Delta and Southwest was an important outcome, creating a template for airline fee structures that San Juan successfully used to secure a P3 for its airport in 2013. Airlines and the airport owner agreed to a similar template in the proposed 2018 P3 lease of St. Louis’s Lambert Airport.

In 2014 the Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report on the subject, which was subtitled “Limited Interest Despite FAA’s Pilot Program.” While discussing a number of the reasons noted in the ACRP report, GAO devoted most of its discussion to financial considerations. As the report noted, “The first key consideration to private-sector airport operators and investors is their generally higher borrowing costs than the public-sector airport owner due to the private sector’s inability to issue tax-exempt bonds.”6

GAO also cited a 2014 congressional report on P3s, which found that “one major reason why the U.S. P3 market has not grown as quickly as in other countries” is that those countries “do not offer tax-exempt municipal bonds.”7 GAO pointed specifically to IRS regulations that prevent the transfer of outstanding tax-exempt bonds to a private-sector operator, which means the airport’s tax-exempt debt must be paid off before a private-sector transfer.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) released a report on this in 2021, several years after the AIPP was inaugurated. After reviewing the limited participation in the APPP and the replacement AIPP, the report made four suggestions for Congress to consider. The most substantive is to offer “the same tax treatment to private and public airport infrastructure bonds.” It noted the obvious disadvantage to existing airports if their bonds became taxable, so the more feasible approach would be to extend “tax-exempt or tax-preferential treatment to airport infrastructure bonds issued by private investors.”8

Of CRS’s other proposed changes, equalizing the percentage match for federal Airport Improvement Program grants for government-run and P3-leased airports would be fair but do little for US airport privatization. Relaxing Airport Improvement Program grant assurances for private airport operators might increase opposition from airport owners and some members of Congress. And liberalizing rules governing PFCs—either by increasing the amount of or removing the federal cap—might increase airline opposition to privatization, as the CRS report notes.

Leveling the Credit Cost of Private and Public Airport Operators

In February 2018, the Trump White House released a report called Legislative Outline for Rebuilding Infrastructure in America.9 That same month, the US Department of Transportation issued a version of this report that focused on transportation infrastructure.10 Part II of the latter includes a section from the White House report on “Innovative Financing to Stimulate Investment” that addresses increasing the use of long-term P3s. That section discusses changes regarding tax-exempt debt on large transportation infrastructure and the use of tax-exempt PABs.11

The proposed reform of tax-exempt surface transportation PABs would broaden their project eligibility to include airports, docks, wharves, and maritime and inland waterway ports—in addition to the highways and transit categories in which tax-exempt PABs have become an essential part of P3-project financing. This change was previously addressed by a bipartisan congressional special panel on P3s,12 which recommended that Congress should “review PAB eligibility to support infrastructure P3s across the jurisdiction of the [Transportation and Infrastructure] Committee.”13

Airports and seaports already issue tax-exempt bonds under US Code 142(a).14 Former White House infrastructure analyst D. J. Gribbin (principal author of the White House report) points out that

142(a) bonds are essentially just typical muni, tax-exempt bonds, i.e. no private activity permitted. Private activity bonds [for surface transportation] were created to allow for tax-exempt treatment but with private activity. So tax-exempt PABs are far better than 142 bonds because they allow for private sector participation.15 (Emphasis in original.)

Aviation attorney John R. Schmidt of Mayer Brown adds that “a long-term airport lease transfers ownership for tax purposes [only]. So once you have a private ‘owner,’ you can’t use those [142(a)] bonds even to finance a new [P3] terminal.”16

These reports propose another important change to PABs that would remove the federal cap on the amount of tax-exempt transportation PABs. When the White House report was written in 2018, the cap for surface transportation projects was $15 billion. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act increased this to $30 billion in 2021. Clearly if the eligibility of tax-exempt PABs expands to include airports (and potentially other transportation infrastructure), a $30 billion limit would soon become a serious constraint.

By contrast, there is no federal cap on tax-exempt municipal bonds. Surface transportation PABs have proved their value in financing highway and transit P3s, so the tax-exempt transportation PABs program should no longer be seen as experimental. As the White House report explains, removing the federal cap should be part of expanding tax-exempt PABs to cover a larger array of transportation infrastructure.

The other proposed tax change in the White House and Department of Transportation reports concerns the tax-exempt status of outstanding bonds of public-sector infrastructure (such as airports) that could be candidates for long-term P3 leases. Current law does not allow outstanding bonds to be exempt from taxes if the facility is leased or sold to private investors. Both reports propose revising “change of use” provisions for two types of cases: when a private entity purchases or leases government assets. Since AIPP does not permit the purchase of commercial airports, only the lease case is relevant to airports.

US Treasury regulations would need to change to permit the facility’s bonds to continue being tax-exempt if it were leased to investors under a long-term P3 agreement, presumably with the private partner becoming responsible for debt service on those bonds. The change would protect the public interest because the government airport owner, as the public partner in the long-term P3 agreement, would retain oversight of the facility’s governance via the long-term agreement’s terms. This is how long-term P3 lease agreements are structured. The US Treasury could initiate this regulatory change if the secretary of the treasury supported it. Alternatively, Congress could revise the current AIPP to require this change in Treasury policy.

Schmidt served as counsel to the airport owner in three potential airport P3 leases: Chicago (Midway), the Puerto Rico Ports Authority (San Juan), and St. Louis (Lambert). In a communication with me, he noted that at one point while those airport P3s were being considered, “Sen. Wyden had a bill to authorize a broader category of tax-exempt financing for privatized operations . . . includ[ing] airports.”17 Schmidt also noted that then–Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels (who had wanted to privatize the Indianapolis airport) testified before a congressional committee in favor of allowing tax-exempt airport bonds to remain in place in the event of airport privatization. Schmidt also suggests that because a P3 airport would still be subject to extensive FAA oversight, there would be “special assurance that all the public purposes would be met.”18

How Much Would the Proposal Change the Proceeds from Airport Privatization?

This report’s thesis, similar to the CRS report’s suggestions, is that a level financial playing field would remove what appears to be the largest barrier to US airport privatization via long-term P3 leases. One hypothesis is that airports are far more valuable than their government owners imagine, such that a long-term P3 lease of a large or medium US hub airport in many cases might yield a significant financial windfall to the city, county, or state that owns the airport. The windfall could be used to pay off a significant fraction (or all) of the unfunded liability of a jurisdiction’s public employee pension system, for example. Alternatively, it could be used to fund public works improvements that had not previously had a funding source (as Indiana did with some of the proceeds from the P3 lease of the Indiana Toll Road) or reduce outstanding debt of the city or county that owns the facility (as Chicago did with some of the proceeds from its P3 lease of the Chicago Skyway).

Since airport privatization is a global phenomenon, we can use that experience to understand how commercial airports are valued. Obviously, every airport is different, leading to the aviation adage “If you’ve seen one airport, you’ve seen one airport.” However, airport privatization begins with a financial transaction, based on a potential P3 team’s assessment of the airport’s economic value. To be sure, size matters, and FAA categorizes commercial airports as large, medium, small, and non-hub. For large airports, a “fortress hub,” in which a single airline has 70 percent or more of the flights, is different from an airport of similar size with a wider array of competing carriers.

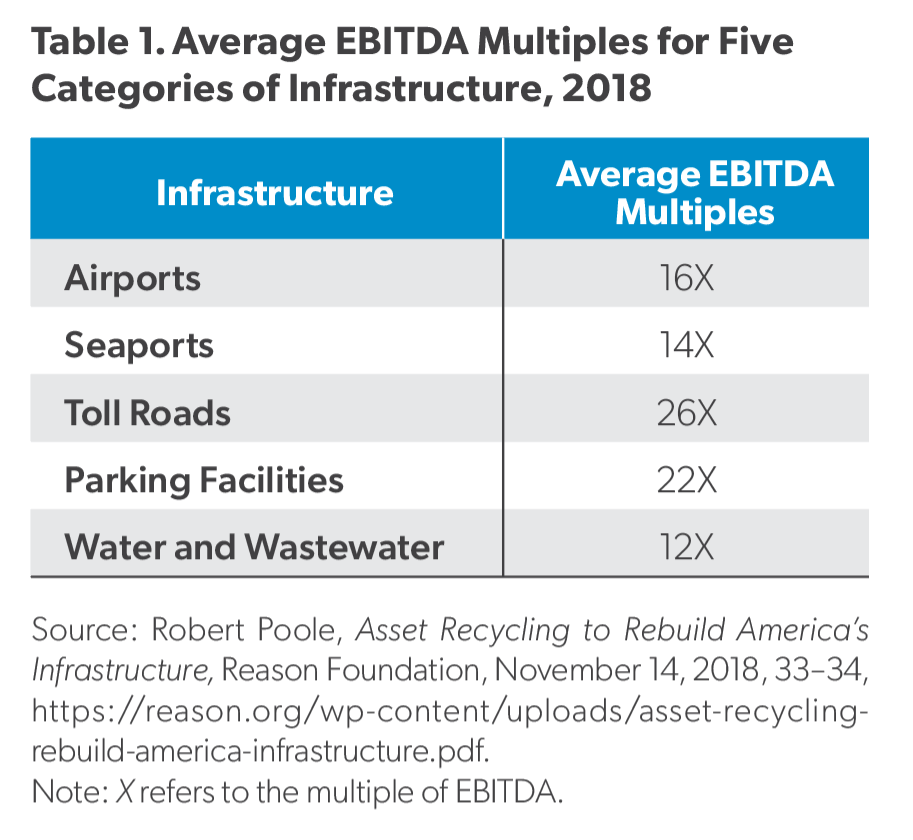

When a P3 team estimates an airport’s market value, it considers these and other factors and its potential for improvements, such as additional terminal and runway capacity. Valuation estimates are based on a measure called EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). Starting with recent EBITDA numbers, potential lessees decide on a multiple of EBITDA based on their assessment of the airport’s potential under a long-term P3 lease. A 2018 study on infrastructure asset recycling identified average EBITDA multiples for five categories of infrastructure, as shown in Table 1.19

These are all pre-pandemic valuation metrics. Toll roads have recovered to beyond their pre-pandemic traffic levels, and so have some European and nearly all US airports, at the time of writing.

If comparable airports in Europe and the United States are each a candidate for a long-term P3 lease, the estimated gross value of each will be the same for comparable EBITDA multiples. Since in most cases the entire lease payment in airport transactions is paid upfront, the European airport owner could expect to receive the gross value, based on the applicable EBITDA multiple to close the transaction.

However, the US airport owner in most cases would receive considerably less. That is because under Treasury regulations, the airport must pay off its outstanding tax-exempt bonds before the transaction can be finalized. The US airport owner would then receive the net value, after debt retirement, unlike the European airport owner, who receives the gross value. However, the gross value of an airport with debt may be less than if it had none (which would be taken into account in the EBITDA multiple used to value the long-term lease).

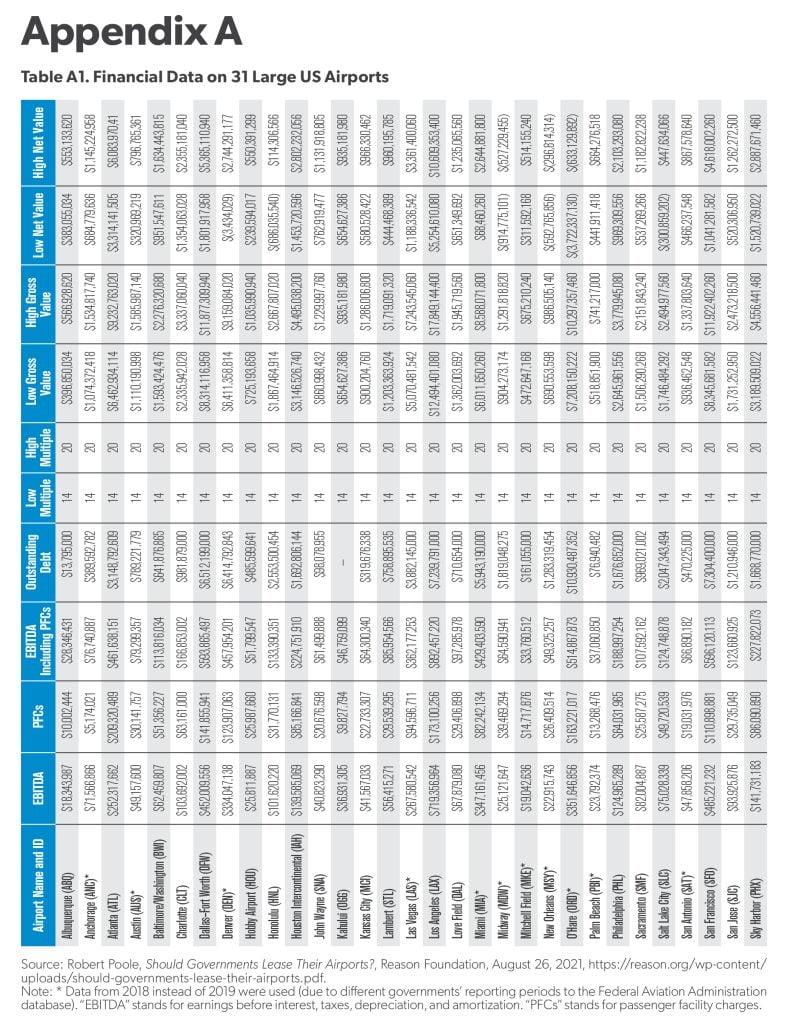

Depending on the level of a US airport’s tax-exempt debt at the time of a P3 lease transaction, the net proceeds may be significantly smaller than the airport’s gross value. In a 2021 study, I drew on FAA data for 31 US airports (large and medium hubs) owned and operated by city, county, or state governments.20 For each airport, financial data for the most recently available fiscal year (2018 or 2019) were obtained from the Certification Activity Tracking System, an FAA database. I used the relevant numbers to calculate each airport’s EBITDA at the time. Also included in the FAA data was each airport’s outstanding debt.

I then computed gross and net valuations for each airport, using both a low EBITDA multiple (14X) and a high multiple (20X). Table A1 summarizes those results. Because they are from 2019, they may not reflect potentially higher valuations in 2025 due to post-pandemic growth in US air travel. There have been fewer global airport P3 lease transactions since the pandemic, so it’s not clear if average EBITDA multiples are higher or lower than those used in the 2021 study. Nevertheless, those valuations are likely to be in the range of current US airport valuations.

Looking first at high-EBITDA-multiple case net valuations (under current US Treasury policy), the five airports with the highest net value were the following:

- Los Angeles (LAX): $10.61 billion

- Atlanta (ATL): $6.08 billion

- Dallas–Fort Worth (DFW): $5.36 billion

- San Francisco (SFO): $4.62 billion

- Las Vegas (LAS): $3.36 billion

In other words, after debt payoff, these net payments would be large windfalls for government airport owners.

However, in a handful of high-EBITDA-multiple cases, the net value after debt payoff (EBITDA multiple minus airport debt) was negative. These tended to be airports that had recently issued a large amount of bonds to expand or modernize:

- Chicago O’Hare (ORD): −$3.72 billion

- Chicago Midway (MDW): −$0.91 billion

- Honolulu (HNL): −$0.69 billion

- New Orleans (MSY): −$0.59 billion

- Salt Lake City (SLC): −$0.30 billion

If airport privatization appeals to airport owners because it provides a windfall payment that can be used for other government priorities, having negative net proceeds would not motivate them to engage in a long-term P3 lease of their airport.

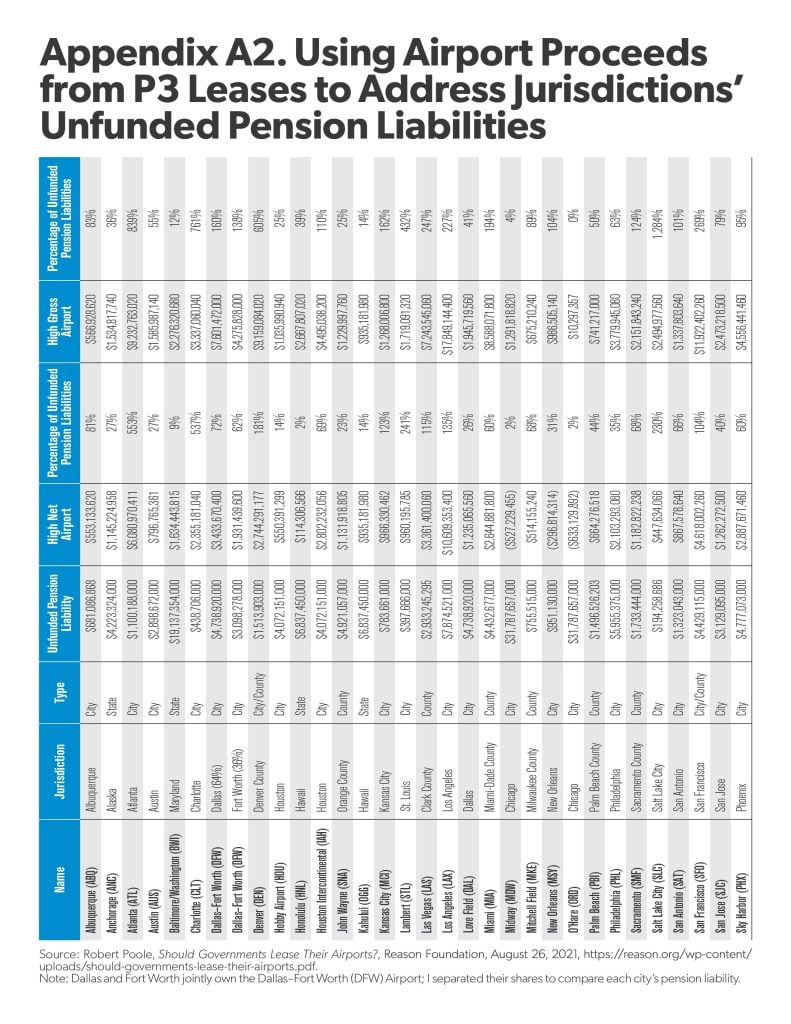

On the other hand, if Treasury regulations were changed to allow airports’ existing tax-exempt bonds to continue to be serviced under the new P3 governance arrangement, the outcome could be considerably more attractive for many airport owners. The 2021 study from which the negative-net-value data are drawn also includes each jurisdiction’s unfunded public employee pension liability (as of 2019) as one potential use of the proceeds from an airport P3 lease. That study uses net proceeds, but the picture is considerably more appealing if gross proceeds are available.

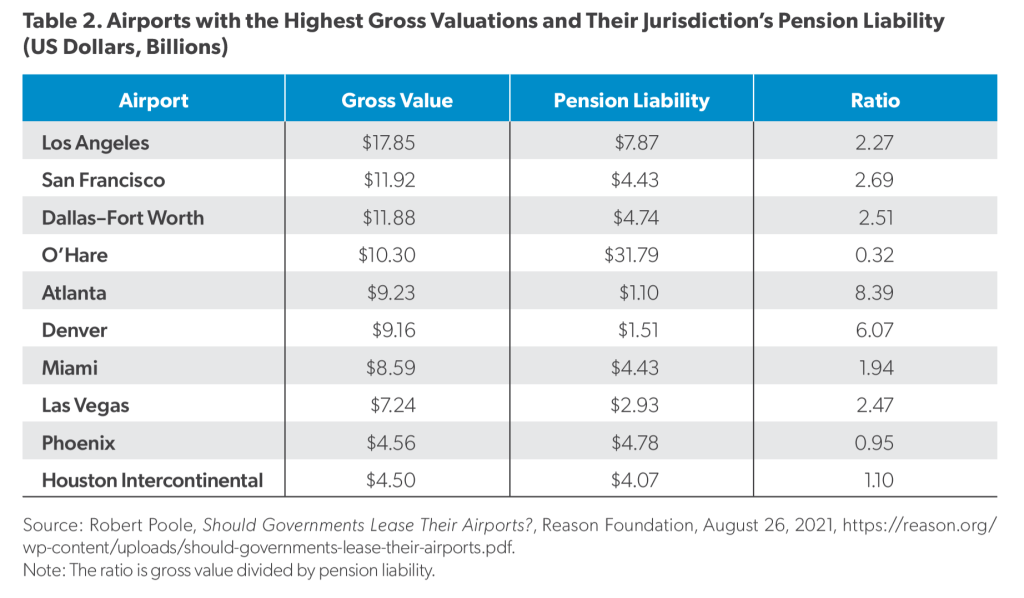

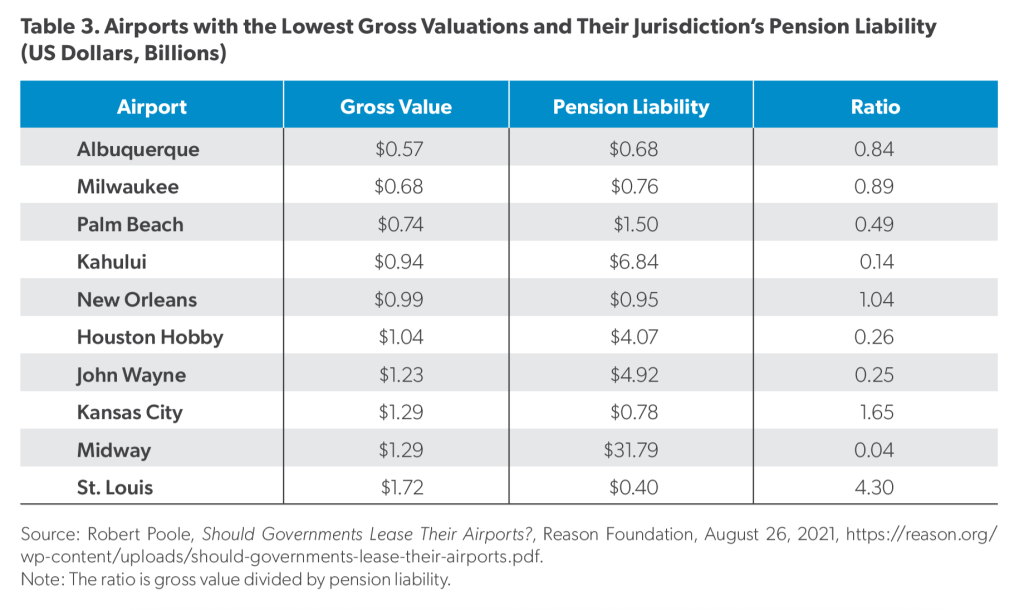

For the 10 airports with the highest and lowest gross valuations, see Tables 2 and 3, which compare these airports with their jurisdiction’s unfunded pension liability.

As shown, if federal policy were changed to enable existing tax-exempt bonds to remain in place following a long-term lease, many jurisdictions could receive enough airport proceeds to pay off all or a significant fraction of their unfunded pension liabilities. Ceteris paribus, that should make airport privatization more attractive to airport owners than is the case under current law. (Details on all 31 airports are in Table A2.)

Since bidders for a long-term airport P3 lease are not responsible for paying off the outstanding airport bonds, allowing those bonds to remain would appear to have little direct impact on the amount the winning bidder would pay for the airport. However, keeping those bonds in place until they are eventually paid off would reduce the amount of new borrowing the P3 entity would need to issue in the early years of the P3 concession. The P3 entity would, by assumption, be responsible for ongoing debt service payments on those bonds until they are paid off, and this could reduce the EBITDA multiple they are willing to pay. Thus, the gross proceeds may be somewhat lower than the numbers in this report.

In addition, if tax-exempt PABs were expanded to include airports and potentially other transportation modes besides highways and transit, the tax treatment for US airport P3s would then be comparable to what applies in most of the world. Tax-exempt PABs have a solid track record in US surface transportation P3s. According to a 2024 report on US P3 transportation finance, PABs totaling $5.55 billion have been issued for 15 revenue-financed highway projects that cost $36 billion. And PABs totaling $9.2 billion helped finance 13 availability-payment transit and highway projects adding up to $27 billion.21

What Is the Impact on Federal Revenues?

The US Treasury and Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation are cautious about expanding tax-exempt bonds on the grounds that if there were no tax exemption, the same transactions would take place using taxable debt (and hence provide additional federal tax revenue). The previously cited GAO report includes a brief discussion of how potential airport privatizations could affect federal tax revenues, but it does not explicitly discuss the case of the P3 entity being excused from paying off existing tax-exempt bonds. It suggests that “any positive effect that a full airport privatization has on federal

revenues is likely to be limited” and that “any full airport privatization [isn’t] likely to have more than a limited negative effect on federal revenues, unless the new private investor generates significant tax losses from the airport investment.”22

However, in seeing the larger picture, in which only one small US airport (San Juan) has been privatized in this century (thus far), one can argue that the Treasury is not getting any corporate income-tax revenue from airport privatization financing today, because no such transactions are taking place. The existing airports are nonprofit, tax-exempt entities. If, hypothetically, reforms allow existing tax-exempt airport bonds to remain in place as part of long-term airport P3 leases, there would be no direct change in federal tax revenue, no matter how many airport P3 lease transactions were to take place.

On the other hand, assuming that airport P3 investors successfully improve the leased airports’ performance, those corporate entities would be subject to federal corporate income taxes on their earnings from these airport projects. By attracting such entities into the US market, the policy change would likely lead to a modest increase in federal corporate income-tax revenue from this formerly nonexistent infrastructure industry. That would be positive for the federal budget.

Something like this has occurred over the past several decades in surface transportation. Since the first P3 toll road project was opened in California in 1995, surface transportation projects developed by P3 companies, and financed based on project revenue streams, have totaled $36 billion. Except for three airport facility projects (terminals and a rental car center), these were all highway projects. Two of the early P3 toll road projects filed for bankruptcy, but nearly all the others have investment-grade bond ratings. Subtracting the two bankrupt projects leaves a net investment value of $34 billion.23 The P3 entities in those projects are expecting long-term profitability, which means they will pay federal corporate income taxes for as long as they operate successful US infrastructure projects.

If US airport long-term P3s were to become feasible, thanks to the policy changes suggested in this report, a comparable new US industry would likely appear over time, and if it proves as successful as the global investor-owned airport industry, it would provide another source of additional federal corporate income-tax revenue. Current surface transportation P3s have lease terms between 30 and 70 years, which is a long period of potential corporate tax revenue. Airport P3s would likely have similarly long terms.

How Might Long-Term P3s Improve US Airport Performance?

US commercial airports are generally well-run, and their city, county, and state owners are mostly satisfied with how they operate. What changes would long-term P3 leases bring about in airport performance, and would those changes motivate their owners to consider a P3 lease?

Howell et al. found performance improvements such as more airlines, a larger number of destinations, lower average airfares due to increased airline competition, increased airport productivity, and greater passenger satisfaction, as measured by ACI’s annual Airport Service Quality survey. The airline-related benefits likely depend on factors such as runway and terminal capacity.

Some US airports are limited in how much they can increase their runway capacity, but capacity can also grow by increasing the average size of their aircraft that use the airport (called “up-gauging”). In 2005, the FAA organized a research project that carried out a strategic game to examine how runway “congestion pricing” would affect airline fleet decisions. Runway pricing is legal under federal aviation law, but no US airport has sought to implement it. The project found that airline schedulers’ primary response to the hypothetical runway pricing at the congested LaGuardia Airport was up-gauging their aircraft serving the airports.24

Another problem at many airports is incumbent airlines controlling gates that they do not fully use. US airports have been gradually changing their use and lease agreements with airline tenants as they expire, shifting to the kind of common-use gates that are far more common in Europe. Common-use gates are still not widespread at US airports, but global airport companies would likely implement them as part of increasing P3-leased airports’ productivity.25

Despite these kinds of benefits, elected officials in many cities, counties, and states that own and operate commercial airports appreciate being able to intervene in decisions about how their airports operate, which often can be termed micromanagement. A former director of Miami International Airport explained this to Sadek Wahba of infrastructure-investor company I Squared Capital:

Airports that are owned and operated by municipalities tend to get stuck in political issues. Everybody wants to have reach into the airport: the airport generates jobs, brings in money . . . and politicians don’t want to let go of that. They want to be able to opine on who should get a contract with the airport; they want to review the budget, even though they don’t necessarily understand it. They do not want to let that go.26

Under a P3 lease, the negotiated long-term agreement between the public partner (city, county, or state) and the private partner would spell out which decisions could be made by which party. Airport investors would likely oppose much of what is currently considered micromanagement, while larger-scale topics would typically be decided jointly by both parties. There would likely be no long-term agreement if the public partner insisted on implementing productivity-limiting micromanagement policies.

Would US Airport Owners Support These Changes?

Most US commercial airports are owned and operated by city, county, or (in a few cases) state governments. Another subset is operated by airport authorities or multipurpose port authorities, which are generally overseen by the governments that created them. If the tax policy changes proposed in this report were enacted, the owners of individual airports would be the deciding players in implementing a long-term P3 lease agreement.

Two US airport trade associations represent this industry and might take positions on these proposals. The American Association of Airport Executives (AAAE) is a membership organization for senior officials of US airports. When airport privatization was being actively discussed or considered (e.g., in San Juan and Midway), AAAE held airport privatization conferences (at which I spoke). The organization did not take a pro- or anti-privatization position. The event’s purpose was to acquaint airport executives with the subject, since there was no history of US airport privatization. AAAE could do likewise if federal policymakers consider or enact the tax law changes I have discussed here.

The other airport organization is Airports Council International–North America (ACI-NA), ACI’s North American division. While ACI-NA does not have a history of organizing conferences on US airport privatization, ACI World—ACI’s European division—has documented the worldwide growth of airport privatization and has statistics on the fraction of passengers using privatized airports in the world’s major geographic areas, as noted earlier.27

ACI-NA would likely support the tax policy changes discussed in this report, and it might join with AAAE in hosting conferences to explore the potential impact of such changes on the US airport industry. ACI-NA could draw on the data and reports that ACI World has developed, much of which is not likely to be common knowledge in the US airport community. Particularly relevant would be the ACI-sponsored study by ICF and Oxford Economics on the growth of airport groups and Howell et al.’s working paper on performance improvements brought about via airport privatization.28

In September 2024, ACI-NA CEO Kevin M. Burke told Aviation Week’s Aaron Karp that because Congress had not increased the federal cap on PFCs in 20 years—leading to a loss of nearly half the annual PFC revenue’s purchasing power—US airports would likely turn to “public-private partnerships to fund the multiples of billions of dollars it takes to build airports.” He noted that airport P3 lease transactions would likely follow the financing model used in Europe and other regions, where companies (often jointly) oversee airport management and development in decade-spanning leases with governments.29 Ultimately, the decision on whether to use P3-friendly federal tax policy changes would be up to individual airport owners.

Conclusion

This report has identified the United States’ unique tax treatment of infrastructure such as airports as a probable reason why US airports have not been privatized or leased as P3s. It suggests two changes to this tax treatment—allowing existing airport tax-exempt bonds to remain in place in the event of a long-term P3 lease and expanding the surface transportation tax-exempt PAB program to airports.

These two changes would enable US airport P3 leases to compete on a level playing field with airport P3 or privatization activity in Europe, Latin America, and the Asia-Pacific. Government airport owners would then receive the gross value of their airport rather than the net value (after bond payoffs), as is true worldwide except in the United States. The resulting windfalls to city, county, or state airport owners would be considerably larger, in some cases large enough to eliminate the unfunded liabilities on the jurisdiction’s public employee retirement system.

The P3-related tax changes this report proposes were included in the 2018 Trump administration’s infrastructure proposal and supported by the secretary of transportation in that administration, which may suggest support from the current Trump administration.

About the Author

Robert Poole is the director of transportation policy at the Reason Foundation. He received BS and MS degrees in mechanical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and did graduate work in operations research at New York University.