- The 20th Conference of the Parties (CoP) of signatories to CITES, the international wildlife trade agreement involving 185 nations will be held in late November in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, where they will discuss 51 proposals to regulate wildlife trade.

- This year, the U.S. has sponsored only four proposals — the lowest in the last 25 years — with none of them supporting increased protections for unsustainably traded flora or fauna.

- Historically, the U.S. has held a leadership role at CITES discussions backed by strong science, but conservationists expressed disappointment at this missed opportunity to help species that urgently need protection in this year’s conference.

- The hope is that the U.S., under its current administration, leaves politics aside, listens to science and supports efforts put forth by other countries to further regulate trade in threatened and overexploited species.

See All Key Ideas

At the end of 2025, representatives from 185 countries will convene in Uzbekistan to discuss the fate of sharks, African hornbills, hyenas, vultures, palm trees and other threatened species.

The group’s decisions will, in part, decide the survival and the future of widely traded fauna and flora as they vote whether to set limits on or bar the international trade of these species and their parts, including fins, heads and skins. This will be the 20th meeting of signatories to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Flora and Fauna (CITES), one of the world’s oldest conservation treaties.

These “Conference of the Parties” (CoP) discussions, held once every three years, will convene from Nov. 24 to Dec. 5 in Samarkand. They offer an opportunity for the world to rein in the unsustainable, multibillion-dollar wildlife trade, both legal and illegal. For species like the elephants, rhinos, tigers and numerous others, trade is the greatest threat to their long-term survival.

The United States has traditionally been a leader in conservation, affording and securing protections to species at risk, including those exploited by trade. But this year, the country’s role seems to have weakened as a leader at CITES: It has sponsored only four proposals for consideration at the upcoming CoP, the lowest in the last 10 CoPs — 25 years. In total, 51 proposals are up for discussion to regulate or ban the international commercial trade of wildlife and its products. For the first time, none of the U.S.-backed proposals support “uplisting species,” affording them greater protection from trade.

U.S. a once-powerful voice for conservation

The U.S. played a vital role in creating CITES and in making it work. The convention was born following a conference at the Department of State auditorium in Washington, D.C., on March 3, 1973 — now celebrated as World Wildlife Day — when delegates from more than 80 countries convened to put an end to unsustainable trade in wild plants and animals.

This followed a decade of meetings with countries in Africa battered by elephant and rhino poaching, led by American ecologist Lee Merriam Talbot, who was also the architect of the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Since then, the U.S., which ranks second in imports of wildlife products after China, has continued to be a powerful voice at the CITES table. It has worked with several countries to stop the commercial trade of all pangolin species; funded initiatives that reigned in trade in Saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica) and in doing so, reversed its decline; helped save fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) and sei whales (B. borealis) from commercial whaling; protected many Amazon parrots from the pet trade; and supported numerous global initiatives to curb wildlife trafficking.

In 2016, the U.S. worked with several nations in Africa and Asia, co-sponsoring proposals that would ban international commercial trade in all pangolin species. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

In 2016, the U.S. worked with several nations in Africa and Asia, co-sponsoring proposals that would ban international commercial trade in all pangolin species. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

“The U.S. has always been a significant leader [at] CITES when species need protection,” said Susan Lieberman, vice president of international policy at the Wildlife Conservation Society.

She is among the world’s top wildlife trade experts, with more than three decades of experience. She worked at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the agency responsible for implementation of CITES regulations in the U.S., for more than a decade, prioritizing support for imperiled species and leading the scientific authority there.

The United States’ leadership role, Lieberman said, comes from the many proposals and discussions the nation has sponsored that were always “very much informed by science.”

However, as the world prepares to debate and discuss the future of international trade in wildlife, both plants and animals, the country’s historical leadership at CITES seems to be waning, worrying conservationists. This is happening at a critical time. Wildlife trade has ballooned into a $10-billion-a-year market and an increasing number of species are entering trade online and offline.

Atrato glass frog from Colombia. Glass frogs, native to Central America and Colombian rainforests, have transparent skin and are in demand as exotic pets in the U.S. At CoP 19, the U.S. co-sponsored a proposal with other range states to regulate trade of all glass frog species. Image © desertnaturalist via iNaturalist (CC-BY).

Atrato glass frog from Colombia. Glass frogs, native to Central America and Colombian rainforests, have transparent skin and are in demand as exotic pets in the U.S. At CoP 19, the U.S. co-sponsored a proposal with other range states to regulate trade of all glass frog species. Image © desertnaturalist via iNaturalist (CC-BY).

With only four proposals and none that uplists species to afford them greater protection from trade, the U.S. seems to have abandoned its leadership role. “It’s a disappointment,” Lieberman said. “The U.S. has co-sponsored nothing that increases protection. I wish it were true that nothing needed protection, but that’s not the case.”

Chris Shepherd, a senior conservation advocate with the U.S.-based NGO Center for Biological Diversity, is also concerned. “The U.S. has always been a strong, supportive player in CITES and a real leader in a lot of conservation issues within the CITES framework,” he said.

Many species in need of stronger protection don’t often get it, Shepherd said, because countries lack the political backing or the resources needed to collect data and draft a science-backed proposal. In the past, the U.S. worked with many other countries and co-sponsored proposals for uplisting.

Before every CoP, member countries sponsor proposals to add or delete species from CITES appendices that allow or ban international commercial trade. Appendix I prohibits all commercial trade, while Appendix II allows regulated trade that doesn’t harm wild populations. To draft these proposals, countries spend years collecting data on traded species and gathering expert opinions.

All submitted proposals are made public about five months before CoP, where members then discuss and vote on them. A proposal needs a two-thirds majority to be adopted as a resolution.

Over the past five decades, these discussions have given more than 40,000 species some protection from unsustainable trade, including pangolins, orchids, lemurs, marine turtles, seahorses, totoabas and vaquitas, as well as iconic big cats and trees, including the Brazilian rosewood. The U.S has sponsored and/or voted for these and many others.

This year’s lack of U.S.’s proactive involvement in protecting species from unsustainable trade, Shepherd said, sets a different precedent. “I think in terms of CITES, it’s a big step down.”

The U.S. delegation for the first CITES CoP held at Bern, Switzerland, in 1976. Image by USFWS via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-2.0).

The U.S. delegation for the first CITES CoP held at Bern, Switzerland, in 1976. Image by USFWS via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-2.0).

What’s in the U.S.-sponsored proposals — and what’s not

Among the four U.S.-sponsored proposals are two that would lower protections from Appendix I to Appendix II for the Guadalupe fur seal (Arctocephalus townsendi), which was driven to near extinction by commercial hunting along the coast of Mexico and the U.S., and the peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus), a raptor whose numbers dwindled because of pesticide use (DDT), but have since rebounded across North America.

The third proposal seeks to delete the Caribbean monk seal (Monachus tropicalis) from Appendix I. It was the only indigenous seal in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, and went extinct in the 1960s due to hunting. Protections came too late for this seal; it’s gone forever, so “that proposal is really just a formality,” Lieberman said. It’s a mere bureaucratic process to tidy up the appendices, she added, in this case because the species is already extinct. “It’s of course sad when that becomes official.”

The last U.S. proposal would amend an existing regulation on American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), exempting farmed plants from trade regulation. The worry here is that once plants or animals are cultivated or captive-bred, it increases the possibility of “laundering” those pulled from the wild among shipments that have permits, a common loophole traffickers already exploit with other species.

These four proposals are a far cry from what was on the table until the end of last year. In a Federal Register notice published Dec. 26, 2024, the USFWS was considering 249 possible proposals.

Two of them — the Guadalupe fur seal and the Caribbean monk seal — were marked as “likely” to be submitted and 55 were marked as “undecided,” pending additional information and consultations with range countries. The rest were marked “unlikely” unless USFWS received more data that warranted a proposal. The tentative proposals were open for public comments.

The undecided proposals included adding the painted woolly bat (Kerivoula picta) to Appendix II. These brightly colored bats, native to South and Southeast Asia, are in demand in the U.S. as décor and trinkets, and the U.S. tops the list of sale destinations. A 2024 study found more than 800 dead bats for sale online over a three-month period, taxidermied and framed. A quarter of them were painted woolly bats.

One of the nearly 250 tentative proposals under consideration by USFWS was the one to add the painted woolly bat to Appendix II. These brightly colored bats, native to South and Southeast Asia, are in demand in the U.S. as décor or trinkets, and their trade is found to be causing a decline in wild populations of the bats. Image by Abu Hamas via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

One of the nearly 250 tentative proposals under consideration by USFWS was the one to add the painted woolly bat to Appendix II. These brightly colored bats, native to South and Southeast Asia, are in demand in the U.S. as décor or trinkets, and their trade is found to be causing a decline in wild populations of the bats. Image by Abu Hamas via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Alarmed, bat conservationists started awareness campaigns, filed a petition to add the species to the U.S. Endangered Species Act, and succeeded in banning the sale of bats online. Despite overwhelming public support for listing on CITES, hopes were dashed when USFWS failed to include them on the CoP agenda.

“This is a huge missed opportunity,” said Shepherd, who is also the co-chair of the IUCN bat trade working group. “The painted woolly bat clearly was something a lot of people… are concerned about.” It’s extremely unfortunate, he said, because it is a species “in a lot of trouble,” and listing it on CITES would have been a big boost for its conservation. A 2020 IUCN population assessment reported a 25% drop in numbers, citing unsustainable trade as one of the drivers of decline.

“The painted bat really just exemplifies what’s happening with many, many other species. Inaction is the greatest enemy to an ever-growing list of species [in decline],” Shepherd said.

In an email statement, a spokesperson from USFWS said it “began its preparations for CoP20 more than a year ago, initiating a robust public engagement process that involves a series of Federal Register notices, website postings, at least one public meeting, and consultations with other U.S. government agencies, foreign government agencies, experts, industry stakeholders, non-governmental organizations, and others.”

The spokesperson said the agency used a “rigorous public engagement process,” to consider “all public input in developing the species proposals and other documents the United States will sponsor and co-sponsor at CoP20.”

The three years until the next meeting will be a long wait for painted bats and a host of other species, such as the endangered blue-spotted tree monitor (Varanus macraei) sought-after in the pet trade, the American horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) and native orchids like California lady’s slipper (Cypripedium californicum), all of which urgently need stronger protection. Not all species can afford that wait.

One species that isn’t on the CoP 20 agenda is the California lady’s slipper, an orchid native to the U.S. West. A tentative proposal would have banned international trade. All orchid species are heavily traded as ornamental plants. Image by Bill Bouton via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

One species that isn’t on the CoP 20 agenda is the California lady’s slipper, an orchid native to the U.S. West. A tentative proposal would have banned international trade. All orchid species are heavily traded as ornamental plants. Image by Bill Bouton via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

“A lot can happen in three years, especially to a species that breeds and reproduces slowly, lives in low densities in the wild and is already threatened by habitat loss and other things,” Shepherd said.

Until then, there’s a temporary fix: Adding these species to CITES Appendix III, which does not require going through the CoP process. Then, exports of these species in countries where they are protected will require permits. However, exports from other countries do not require documents. In contrast, all exports of Appendix I and II need permits for international trade.

“A range state can list the species on Appendix III at any time,” Shepherd said. “The more range states that list the species in Appendix III over the coming three years, the better.”

Current U.S. proposals are an outlier to past trends

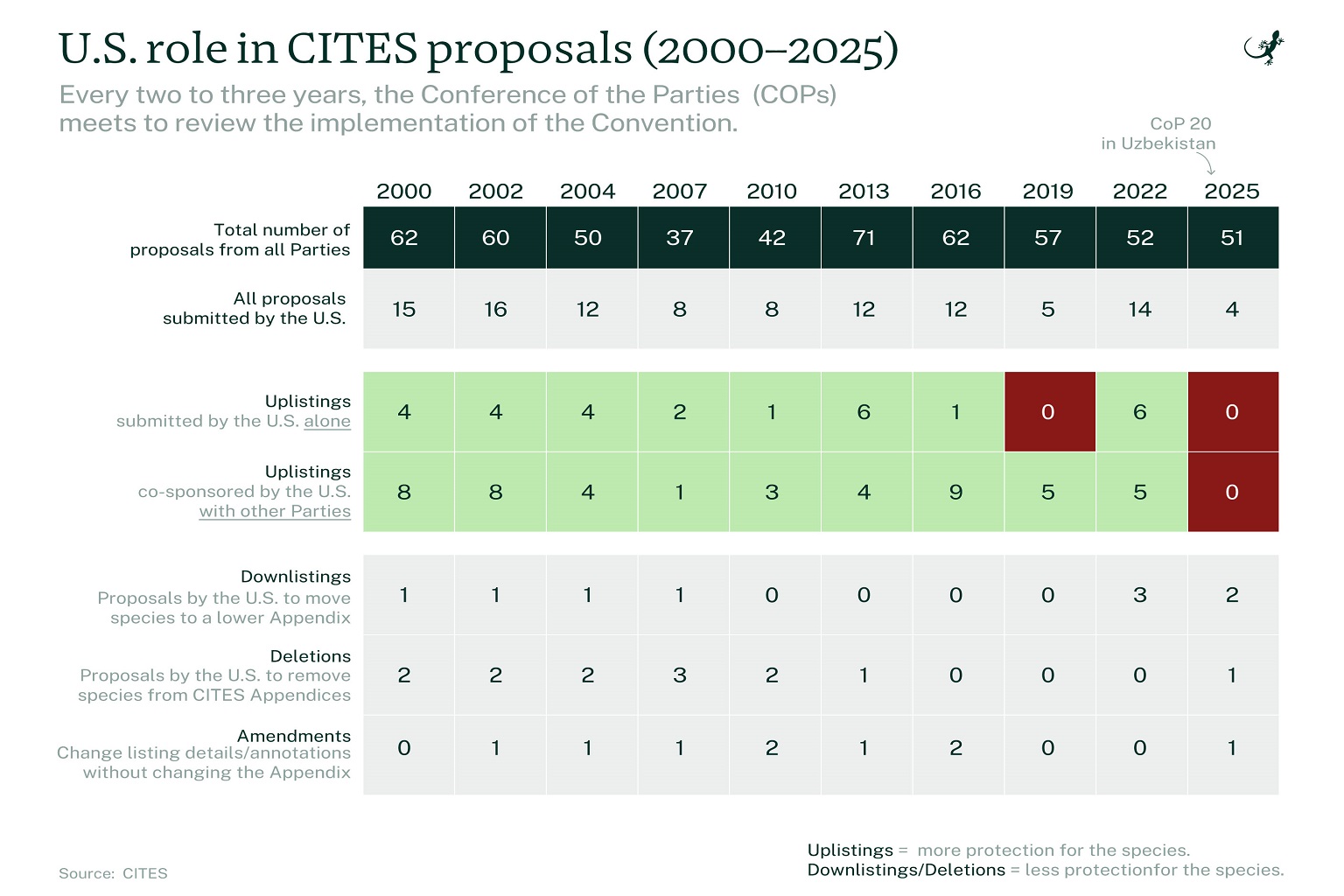

Glaring differences emerged when Mongabay analyzed the U.S.-sponsored proposals for the upcoming CoP and compared them with proposals sponsored in the previous 10 meetings, dating back to 2000. On average, the U.S. sponsored or co-sponsored 10 proposals at each, with the second-lowest — five proposals — submitted at the 18th CoP in 2019 during the first Trump administration.

For context, between 50 and 60 proposals are considered at each meeting. CoP14 in 2007 considered the fewest, with just 37, but even then, the U.S. sponsored eight, including three that lobbied for species uplisting.

Analysis of U.S.-sponsored CITES CoP proposals in the last 25 years. Image by Mongabay.

Analysis of U.S.-sponsored CITES CoP proposals in the last 25 years. Image by Mongabay.

Not submitting a proposal does not mean the U.S. won’t support greater protection for traded species: The proof will come in how U.S. delegates vote at the conference. However, the countries that sponsor proposals are given priority to speak at an extremely time-crunched event. They also have larger sway in discussions and the soft power to lobby other countries’ support. This year, the U.S. will, for the first time, lose that opportunity.

The USFWS did not comment on Mongabay’s questions on why fewer proposals were submitted and the absence of any that supported stronger protections.

Lieberman said it might be because the people in charge of putting together proposals at the agency may not be familiar with the process: The current administration replaced much of the former staff with new people.

“I hope the U.S. will come to CITES, will listen to the science and not make decisions based on politics or which country they like that day,” Lieberman said. “It’s strong support for conservation … for multilateralism. We’re seeing a change in that in this administration. We’re seeing a walking away from multilateralism.”

Conservation, like everything else, is political, and both Lieberman and Shepherd expect some politics might be at play at the upcoming CoP. But they said countries need to look beyond the political smokescreen, as the U.S. did when it co-sponsored a proposal in 1997 to list 23 species of sturgeons (Acipenseriformes spp.) on Appendix II.

Lieberman recollected how the U.S. worked with Iran, despite diplomatic tensions, to discuss how to save sturgeons and get them listed on CITES. In the past, she said, “the U.S. would sit down with countries [to] talk about conservation, regardless of the politics of the country.”

She added context. Historically, “the U.S. scientific authority has always been very, very strong, with great people. … We’re hoping the U.S. listens to the science — not just politically which country submitted it and what we think of that country.” She called it “a dangerous slope,” emphasizing that “if countries base their decisions on politics and not conservation, we will lose species.”

There are many proposals the U.S. can vote on to uphold conservation, such as adding Africa’s okapi (Okapia johnstoni) to Appendix I, along with Galapagos marine (Amblyrhynchus spp.) and land iguanas (Conolophus spp.) that have been hammered by suspicious illegal trade; and uplisting several plants and shark species that are already threatened.

“Conservation is always an uphill battle, and ideally, leaders of countries would be supporting the conservation of their own species and working as a global network through CITES to protect global biodiversity and to ensure trade is not unsustainable,” Shepherd said. “Clearly, that’s not the case right now … we’re living in very unusual times.”

One of the four U.S.-sponsored proposals would lower protections from Appendix I to Appendix II for the Guadalupe fur seal, which was once driven to near extinction by commercial hunting along the coast of Mexico and the U.S. Image © Programa Marino del Golfo de California via iNaturalist (CC BY-NC-SA).

One of the four U.S.-sponsored proposals would lower protections from Appendix I to Appendix II for the Guadalupe fur seal, which was once driven to near extinction by commercial hunting along the coast of Mexico and the U.S. Image © Programa Marino del Golfo de California via iNaturalist (CC BY-NC-SA).

Banner image: Tigers were among the first species added to CITES Appendix I in 1975 to halt the illegal trade of these cats and their parts. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

Citations:

Morton, O., Scheffers, B. R., Haugaasen, T., & Edwards, D. P. (2021). Impacts of wildlife trade on terrestrial biodiversity. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5(4), 540–548. doi:10.1038/s41559-021-01399-y.

Coleman, J. L., Randhawa, N., Huang, J. C., Kingston, T., Lee, B. P. Y., O’Keefe, J. M., . . . Shepherd, C. R. (2024). Dying for décor: quantifying the online, ornamental trade in a distinctive bat species, Kerivoula picta. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 70(4). doi:10.1007/s10344-024-01829-9.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.