Britain is in a “very good position” to win the European space race and beat Norway to the continent’s first launch into orbit, Sir Chris Bryant, the space minister, has said, as he announced the government would take full control of the UK Space Agency.

The agency has been a quango, operated at arm’s length from the government, but is to be taken in-house at the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, in what ministers hailed as a “major step to boost support for the UK’s space sector”.

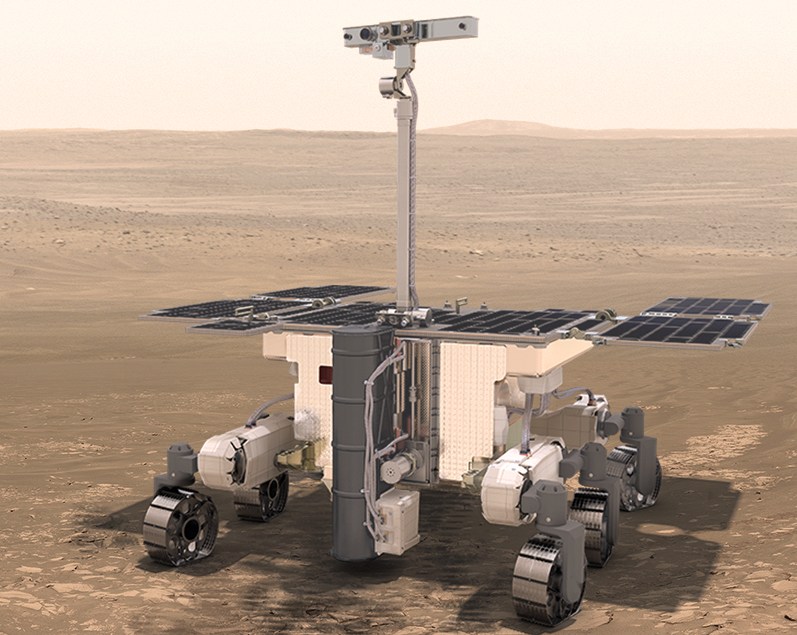

Space-related activities, including the design and building of satellites, are worth more than £16 billion annually to the UK economy. The Rosalind Franklin space rover, set to launch to Mars in 2028, was built in Stevenage, while the UK has a full-time astronaut, Rosemary Coogan, in training with the European Space Agency (ESA).

The Rosalind Franklin rover

Bryant said this week that the UK reaped returns of £5 to £6 for every £1 invested in the space sector.

At present, satellites built in Britain have to be shipped overseas to be launched into orbit aboard rockets such as those flown by Elon Musk’s SpaceX from launchpads in the United States, or on ESA rockets that blast off from French Guiana in South America.

No orbital launch has been achieved successfully from a launchpad on European soil, but Britain is racing against Norway to achieve this first. An attempt from Spaceport Cornwall in 2023 failed when the rocket made it into space but crashed back to Earth before making it into orbit.

The SaxaVord Spaceport, built on the site of an old RAF base on the island of Unst in the Shetland Islands, is set to be the first UK site to blast a rocket into orbit, with a test flight expected late this year or early next. Their timetable was set back after an engine exploded during a test on a launchpad last summer.

• Shetland spaceport says this is why do tests after rocket explodes

The spaceport also announced last week the death after a short illness of its co-founder, Frank Strang. He had battled against scepticism from local officials to build the site with his wife, Debbie, and friend Scott Hammond, who will take over as chief executive.

Their main rival is Andoya, a spaceport in Norway, which suffered its own setback in March when a test rocket crashed back to Earth.

The rocket Spectrum crashes and explodes on a test flight from Andoya Spaceport in Norway

Asked if Britain could still win the European space race, Bryant told The Times: “I think we’re in a very good position.”

Britain’s location in northern Europe gives rockets easy access to polar orbits, where satellites travel from north to south above the Earth rather than around the equator, launching out over the sea with no need for rockets to fly over populated areas.

Sir Chris Bryant was appointed a minister in the science department on July 8 last year

MICHAL WACHUCIK/ABERMEDIA

Bryant said: “We can achieve things that others, including some of the biggest players in the European Space Agency, can’t achieve. France, Germany, Italy, Spain — they’re not going to be doing this.”

He said Britain wanted to be a world leader in a new era in which space telescopes, probes and satellites are assembled and repaired while in space. “With the right support, UK space firms could capture a quarter of the global market for in-orbit servicing, assembly and manufacturing,” a government statement said.

The Unst spaceport under construction in 2023

SAXAVORD/PA

The UK Space Agency employs 320 people and distributed half a billion pounds of funding to the UK space sector in 2024-25. Bryant said: “Bringing things in-house means we can bring much greater integration and focus to everything we are doing while maintaining the scientific expertise and the immense ambition of the sector.”

The government said the move would “cut duplication and reduce bureaucracy”, but Bryant said cutting jobs was “not the aim” of the move.

Dr Paul Bate, chief executive of the agency, said: “I strongly welcome this improved approach to achieving the government’s space ambitions. Having a single unit with a golden thread through strategy, policy and delivery will make it faster and easier to translate the nation’s space goals into reality.”