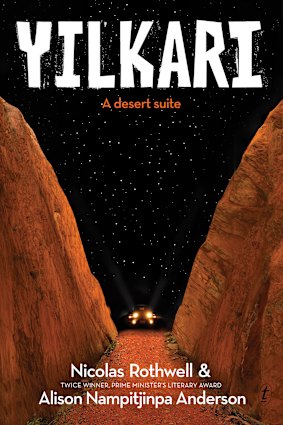

Yilkari by Nicolas Rothwell & Alison Nampitjinpa Anderson.

FICTION

Yilkari: A desert suite

Nicolas Rothwell & Alison Nampitjinpa Anderson

Text, $34.99

Nicolas Rothwell has written eight books but Yilkari is a first: a collaboration, co-authored with his wife, Alison Nampitjinpa Anderson, a Luritja-Pintupi artist and writer from the Western Desert community of Papunya.

Yilkari offers a vision of the Western Desert filled with drifters and sundowners, vagrants, vagabonds, loners and backpackers and desert specialists. The world through which its unnamed narrator journeys, accompanied by various companions, is one you can hear and smell: desert oak and dunes, burnt mulga plains, ironwoods, sacred sites, conception places, station homesteads, bungalows, Queenslanders, ageing diesel pumps and sorry camps and caravan parks attended by frantic camp dogs.

An Australian born in Europe, the narrator seems to be a journalist who has returned, perhaps recently, from the Middle East. We learn that he is travelling west, to Karilwara, Ngaanyatjarra country. He is hoping to see an old friend and man of high degree, Mr Giles, a traditional doctor who is also a famed artist busy navigating the humbug of craven dealers, gallery folk and “a praetorian guard of collectors from down south”.

Over the following four chapters – each vignette is linked and works to refract its neighbours – he journeys further across the country. This trip becomes a search for a sense of place. The country is understood as something to be taken in, read and lived and travelled through, loved and feared and complicated by and invested in. A gateway through which the past becomes clearer and the self opens to a kind of unguarded reckoning.

Author Nicolas Rothwell.

The first of the narrator’s travelling companions is Jan Valentin, a Central European composer and “brother spirit” brought up in Siberia. Valentin reads the land as a wilderness. For the narrator, it offers refuge. Valentin’s presence prompts memories of the fall of the Berlin Wall, erected as the narrator is born, toppling by the time he first meets Valentin. Such memories are among the few we learn of the narrator’s past; mostly he serves as a receptive ear for the stories his companions offer.

Like Valentin, the narrator fears having expended or lost touch with the vitality of his art. His practice of listening and conversing mirrors the practice Valentin describes as embodying the ideal approach to music: “Sounds from outside come into you. They crystallise inside you.” The narrator’s relationship with his itinerant father has perhaps encouraged him to seek belonging.

Hence the book’s title, a word meaning, among other things, “clarity; everlastingness”. The narrator’s travelling companions are not just interlocutors but “guarding spirits”, each of whom offers a different but connected kind of Yilkari. One companion, Dylan, calls it the “dream of union”: a union that is both metaphysical and tied to place, to the fact of country as a living, charged presence.