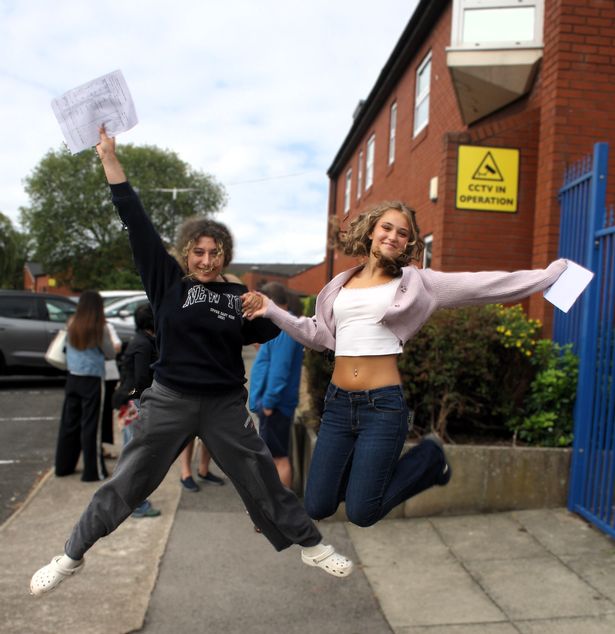

A fifth of pupils in Greater Manchester achieved top grades Charlotte and Emilie from Withington Girls’ School both achieved top GCSE grades – but many of their peers did not

Charlotte and Emilie from Withington Girls’ School both achieved top GCSE grades – but many of their peers did not

As teenagers across the country receive their GCSE results today (August 21), the gap between London and the rest of the country has widened again. Around a fifth of pupils in Greater Manchester scored a grade seven or above this year, equivalent to an A or an A*.

This is higher than the rest of the region as 18.8 per cent of pupils achieved top grades in the North West of England. But Greater Manchester, and the rest of the country, is still lagging behind London and the South East – and the gap is only getting wider.

Over a quarter of pupils in London (28.2pc) have achieved a grade seven or higher this year. In the South East it’s 24.7pc.

That’s up from 25.7pc and 23.5pc respectively since 2019. But across the rest of the country, the gap has grown since the pandemic.

Sign up to the MEN Politics newsletter Due North here

Similar patterns were seen in last week’s A-Level results when the gap between the best and worst regions widened yet again.

This widening gap has been blamed on the pandemic which affected schools in areas with higher infection rates more profoundly.

Students collect their GCSE results in Lowton

Students collect their GCSE results in Lowton

On average, there was an additional 41 days of lockdown in the North of England meaning children in the region missed school more.

In Manchester alone, more than 3m days of face-to-face schooling were lost during the pandemic – around 19 million hours in total.

Henri Murison, chief executive of business-led think tank and lobbying group the Northern Powerhouse Partnership, said: “We know this generation of children were affected by COVID-19, and the resulting regional inequalities are of significant concern.

“In the North and Midlands, the gap in grade 7 and above with London has not closed since the pandemic. It remains more than ten percentage points in the North East, East Midlands and Yorkshire & the Humber – a significantly wider gap than before COVID.

“In the North East, the gap with London narrowed by just 0.1pc, and only because London’s results fell from 2024, not due to any real improvement here.

“This year’s cohort started secondary school in September 2020, with much of their early education shaped by lockdowns and disruption – an impact that could have been mitigated if then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson had invested the level of COVID recovery funding experts said was needed.”

Northern Powerhouse Partnership chief executive Henri Murison(Image: Northern Powerhouse Partnership)

Northern Powerhouse Partnership chief executive Henri Murison(Image: Northern Powerhouse Partnership)

Education secretary Bridget Phillipson has described the widening gaps between different parts of the country as ‘unacceptable’.

But even before the pandemic, London and the South East were consistently outperforming the rest of the country for years.

So why do these gaps exist in the first place? One factor could be funding and the huge difference schools in each region receive.

In 2023, the ‘Child of the North’ revealed that schools in the North West receive £654 less per pupil on average than those in London.

Last week, Health Equity North, which was behind that report, said that child poverty is also a major driver of educational inequalities.

London, which suffers from high levels of poverty in some areas, has not always outperformed the rest of the country in education.

Join the Manchester Evening News WhatsApp group HERE

Much of the success of London’s schools has been put down to a programme that was introduced by the last Labour government.

At its peak, the London Challenge programme had a budget of £40m a year to fund support for under-performing schools.

The ‘City Challenge’ programme was eventually extended to Greater Manchester in 2008 with a budget of £50m over three years.

But while schools London continued to improve under this programme, the picture in Greater Manchester was more ‘patchy’.

According to an evaluation of the programme by the Department for Education written in 2012, this was partly down to timings.

While the London Challenge lasted eight years in total, the report noted, the Greater Manchester Challenge lasted only three.

The ground-breaking programme was launched in London five years before it was rolled out elsewhere

The ground-breaking programme was launched in London five years before it was rolled out elsewhere

“While Greater Manchester and the Black Country made substantial progress in the three years they had,” the report added, “a five-year period would probably have enabled them to make even more progress, and to ensure that the improvement was sustainable.”

Outside of this scheme, which ended in 2011, the real-terms value of the Pupil Premium, that gives state-funded schools with disadvantaged pupils more money, has fallen under successive governments, according to the Northern Powerhouse Partnership.

Mr Murison, who is the Northern group’s chief executive, added: “If the Education Secretary is serious about tackling the persistent disadvantage faced by white working-class children, spending decisions by her department must prioritise the poorest pupils, or risk wasting yet more of the North’s young talent.”

Last week, education secretary Bridget Phillipson said that the government would be ‘taking the best’ of the renowned London Challenge and applying it to other parts of the country as part of its efforts to improve schools outside of the capital.

Responding to the GCSE results on Thursday (August 21), she said: “Behind every grade lies hours of dedication, resilience and determination and both students and teachers should feel an immense sense of pride in what they’ve achieved today.

“But while results today are stable, once again we are seeing unacceptable gaps for young people in different parts of the country.

“Where a young person grows up should not determine what they go on to achieve. Through our Plan for Change – from revitalised family services to higher school standards – I am absolutely determined to make sure every young person, wherever they live, has the opportunities they deserve.”