Over the last five years, the Architectural Heritage Fund (AHF) has handed out £35 million in grants and loans to support community-led regeneration of historic buildings.

In the last 12 months alone, 157 projects have received backing from the organisation, which channels money from government sources and philanthropic funding foundations to help social enterprises and charities, particularly in deprived communities.

Many of these, such as Mosedale Gillatt Architects’ work for the Tyne & Wear Building Preservation Trust, rescuing a 19th-century former bank in Sunderland, involve full professional teams which include architects.

In some cases architects are going even further, hopping the fence from designer to project instigator and going above and beyond their traditional remit.

By embedding themselves within their own local communities, they have effectively become the client on heritage regeneration projects, delivering grassroots social and economic impact.

AHF chief executive Matthew McKeague believes architects are well-positioned to take on this role, helping guide ‘good design decisions’, especially where a group lacks experience or is ‘doing a project for the first time’.

The empty, 200-year-old B-listed Glebe building in Inverclyde is being turned into a heritage skills and cultural hub by not-for-profit organisation Creative Regeneration

He tells the AJ: ‘Where we see architects really add value is when they work collaboratively with other key professionals and the community.

‘This collaboration often helps create schemes that adopt a high-quality design and conservation approach, but that take account of other vital elements: making sure the design fits the business plan, management and maintenance is properly considered and costed, and that plans are adaptable to changing circumstances.

‘That type of advice and guidance is invaluable in creating sustainable, long-term projects.’

We spoke to three architects who are doing just that.

Bruce Newlands, founder of Kraft Architecture and co-founder of Creative Regeneration: The Glebe, former sugar refinery, Greenock, Inverclyde (1831)

Creative Regeneration Trustees Bruce Newlands (left) with Alec Galloway and Finlay Campbell

How did you first get involved with this project?

I’d become directly involved with community groups when I set up in sole practice in 2008 after leaving Anderson Bell + Christie. I saw it as an extension of what I wanted to pursue: both working for, but also deeply embedded in, community development.

After founding MAKLAB, Scotland’s first digital makerspace, I helped set up the Innovation Factory as part of (BE-ST) Built Environment Smarter Transformation in around 2017.

In 2018, I moved to Inverclyde and co-founded the volunteer-run Inverclyde Shed, helping them with a £1 million renovation of a derelict shed in central Greenock.

At the same time I was working with the Woodlands Community Development Trust, supporting local community groups fight planning appeals. This led to the formation of Creative Regeneration. Together with other creatives and educators, we want to create a community-driven vehicle to deliver local regeneration projects focusing on STEAM (science technology, engineering, art and mathematics).

Like most architects, I’ve a wandering eye. On my first visit to Inverclyde, the Glebe jumped out. It’s a striking building, mainly because of the decay all around it. It stands silent and defiant, waiting for something hopeful to happen.

What is the project trying to achieve?

Creative Regeneration has built a community organisation to revitalise the Glebe and another building in Gourock called the Old Library. Both are focused on bringing new community STEAM learning to Inverclyde as well as regenerating under-used buildings.

Inverclyde has suffered in recent decades like many towns. The Glebe is a £5.5 million project that will create a maker-space with partners NEXTFab, a digital rehearsal space for international theatre group Vanishing Point, as well as exhibition areas, offices and community spaces.

The crowning element will be a national stained-glass school and retrofit hub. To the existing 1,500m2 floor area (over five floors) we are adding an additional 300m2 glazed roof extension.

How has being an architect helped navigate those challenges?

My background has made navigating the early feasibility stages, liaising with and commissioning consultants, speaking to funders and working with partners, a lot easier than for an organisation without that experience. It’s also given my fellow trustees confidence in making some decisions. There are technical aspects about energy and building physics, which I focus on in practice, that have also helped us get ahead to RIBA Stage 4 proposals quite quickly.

Proposed dance space on the third floor of the revamped Glebe

Have you done any design work yourself?

Yes, I’ve done the architectural design work to date with the assistance of Balfour Engineering, Design Workshop Engineering and Carbon Futures Energy Consultancy.

We’ve also been supported by Brown + Wallace on the building condition survey and Dalgety Design with early architectural visualisations. These were crucial for helping us communicate the concept, consult on the vision and build our community membership which now exceeds 500 people.

We’re currently looking at commissioning a suitably accredited conservation architect to focus on the heritage elements of brick-and-mortar repair, progress statutory and funding applications, tender information and provide on-site assistance.

What role has the AHF played in turning your vision into reality?

It has played a crucial role and at a critical time. Its early-stage project viability support [£9,480] enabled us to commission a baseline measured survey, building condition survey and RIBA Stage 4 cost plan.

This allowed us to develop design proposals and build a business case which, in turn, informs discussions with capital funders. Project viability support really has been a powerful intervention.

What would you say to other architects about getting involved in projects like this?

Embedding myself in community projects, particularly ones local to me, is part of how I want to practise as an architect.

I’m delighted to be able to use my skills to help the community progress projects. I still practise as a consultant but have found that working on community-led projects is the most rewarding aspect of what I do.

The ground floor proposals for the historic Glebe building.

Emily Pieters, project director, Harmony Works: Canada House, former head office of Sheffield United Gas Light Company, Sheffield (1874)

Emily Pieters, project director, Harmony Works: Canada House, former head office of Sheffield United Gas Light Company, Sheffield (1874)

How did you first get involved with this project?

It all began with a conversation that mixed friendship, music and architecture. Ian Naylor and Martin Cropper – lifelong champions of music education in Sheffield and friends from childhood orchestra days

– approached me in 2017.

They had discovered that Canada House, a Grade II*-listed building in the heart of Sheffield, was for sale and needed someone ‘who knew about buildings’. I’d recently moved back to Sheffield, where I grew up.

Before they allowed themselves to get too excited, I connected with the University of Sheffield’s School of Architecture and Landscape, where a group of master’s students explored the building’s potential through a ‘live project’. Their ‘what if’ scenarios brought Canada House to life in new ways, gave us the name Harmony Works, and – crucially – helped us secure buy-in from politicians and funders with a compelling story and visuals.

Tell us about the project

It’s about far more than a building. It’s about giving music education in Sheffield the home it has long deserved. Both Sheffield Music Academy and Sheffield Music Hub are thriving but operate in unsuitable, dispersed spaces that weren’t designed for music or expansion.

The vision is to bring these organisations together along with a range of committed partners in a new centre for music education, based at Canada House. The project will not only provide inspiring facilities for young people and audiences of all ages, but also rescue and restore a Grade II*- listed city-centre landmark that risks further decline. In doing so, it will anchor a wider cultural regeneration of Sheffield’s Castlegate quarter.

From an idea with no funding, we’ve grown into a charitable incorporated organisation with political backing and over £13 million raised, including major grants from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Arts Council England and South Yorkshire Mayoral Combined Authority as well as £1 million recently received from The Garfield Weston Foundation.

It’s been a very steep learning curve for me, including governance, VAT, business planning and fundraising, but we’ve made extraordinary progress from a standing start.

The Italianate exterior of the Grade II*-listed Canada House in Sheffield’s Castlegate

How has being an architect helped navigate those challenges?

Having an architect embedded in the early stages can completely shift what’s possible – especially when the architect is the client. Problem-solving, curiosity, advocacy and patience have all been crucial skills. Understanding the long journey of a project, while holding on to a clear end vision, has helped sustain motivation and build confidence among stakeholders.

It’s also meant I can speak confidently to funders about capital costs and risk, and actively engage in discussions around complex decisions like balancing acoustics, cost, ventilation and historic preservation. That depth of understanding helps bring people together around the best solution.

Have you done any design work yourself?

No, but I’ve been closely involved at every stage as client, from briefing to decision-making, and discussions around principles of conservation/found space.

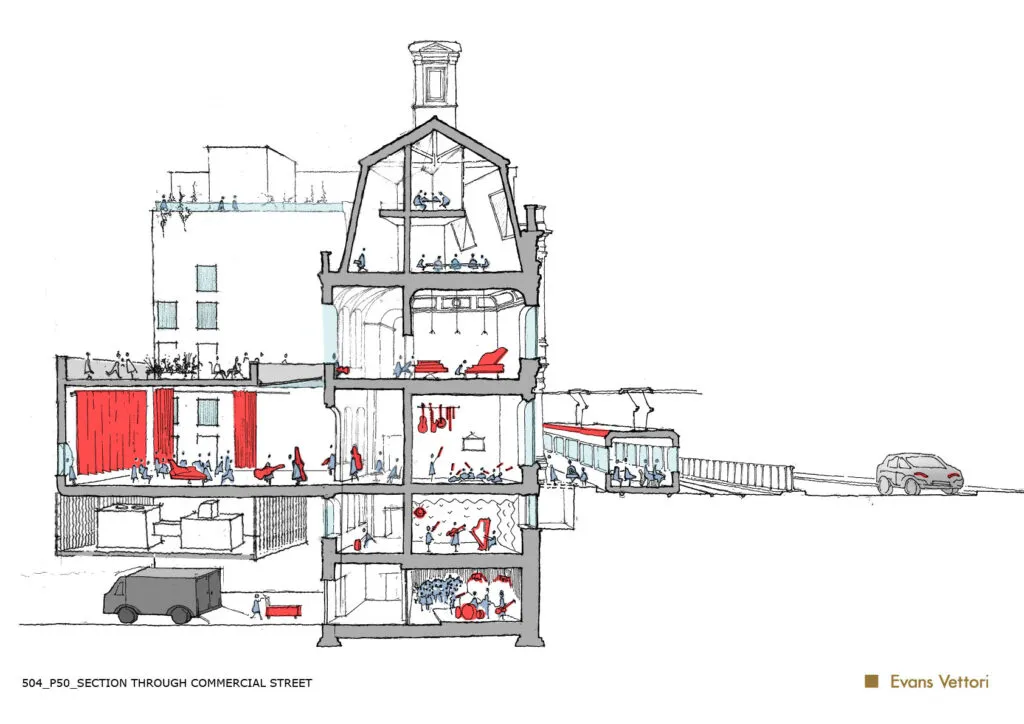

We’ve a superb and committed team of design consultants, including architect Evans Vettori, Arup, JP Fire, ADT Acoustics, and Turner & Townsend, and my role is to guide without interfering.

What’s helped enormously is having worked on the other side of the fence for much of my career, most of which I spent at Benoy. I understand the complexity, the iterative process and the absolute need for timely, clear decision-making, which has made me a better, more enabling client.

A section through the building, showing arrangements of music activities drawn u by Evans Vettori

What help has the AHF been in turning your vision into reality?

They were there at the very beginning of our journey – the ones who got us moving. Their early belief in the project and willingness to fund that uncertain first phase was instrumental in turning vision into viable plan.

Their support came in two vital phases: a £7,500 project viability grant enabled us to assess the project’s financial and architectural feasibility; a follow-on development grant of £100,000 allowed deeper engagement, supporting business planning, valuations, early design and survey work, and a successful pre-application to Sheffield City Council. Without that, we couldn’t have reached this point.

What would you say to other architects about getting involved in projects like this?

There’s something deeply satisfying about being the client. It’s enabling and creative in a different but equally fulfilling way. I’ve been surprised by how much I’ve enjoyed it.

Architects have an instinctive understanding of how projects come together. That makes us uniquely well-placed to step into client roles and to make a real success of it.

Stephen Anderson, chair of Valley Heritage and director at Buttress: The Alliance, former Lancashire & Yorkshire Bank, Bacup (1878)

Stephen Anderson, chair of Valley Heritage and director at Buttress: The Alliance, former Lancashire & Yorkshire Bank, Bacup (1878)

How did you first get involved with this project?

I moved to Rossendale in Lancashire in 2001 and soon began volunteering at the local charity Rossendale Civic Trust (RCT), which advocates for high-quality development and conservation of the historic environment. I was working at AEW Architects at that time.

Over time, I realised Rossendale needed a different kind of organisation to address its disused and derelict heritage assets. We could see that significant buildings were being lost in favour of poor-quality new developments, which inspired the idea of a building preservation trust.

By 2013, we had secured a start-up grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund. Valley Heritage became a constituted charity in December 2015.

Our initial focus included challenging projects like Waterside Mill. Supported by the AHF, we conducted feasibility studies, collaborating with a social housing provider and the local authority.

However, after three failed attempts to secure substantial funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, I learned that personal credibility does not necessarily translate to organisational credibility.

We pivoted, concentrating on smaller projects aligned with Valley Heritage’s educational goals to build a track record.

The Alliance, Bacup, Lancashire, a former bank transformed into homes and co-working spaces

Tell us about the project

In 2019, we began our first capital project, completed in 2022 despite the challenges of the pandemic.

The Alliance, a Grade II-listed former bank in Bacup, was transformed into homes and co-working spaces as part of Bacup’s High Street Heritage Action Zone.

What help has the AHF been in turning your vision into reality?

The project was supported by a £200,000 AHF loan for acquisition and a £350,000 grant for refurbishment. Valley Heritage’s team, with three volunteer architects, contributed concept designs, expediting the process.

Concurrently, Valley Heritage’s sustainability was bolstered by revenue support from the AHF’s pilot Heritage Development Trust programme, enabling the organisation to rapidly develop.

Historic England now supports Valley Heritage with a three-year grant, helping tackle Rossendale’s most challenging heritage assets and developing a pipeline of projects.

What would you say to other architects about getting involved in projects like this?

Valley Heritage has been formative for me and, despite all the challenges that go with building an architectural career, I’d encourage other architects to take on similar roles.

The positive impact such roles can have on communities has proved a source of motivation and complemented my career, even when, at times, competing for my capacity.