We have been described as fans of brutalist architecture, so when new book Brutalist Interiors landed on our desk, it was cause for excitement. The tome offers a deep dive into the powerful, fascinating and often controversial movement’s spaces – bringing to the fore a rich and international selection of important architecture, and luxurious, swoon-worthy photography. Created for independent publisher Blue Crow Media and edited by Derek Lamberton, the title presents a global survey spanning more than 100 interiors in 30 countries. We caught up with the editor to find out more.

Discussing ‘Brutalist Interiors’ with Derek Lamberton

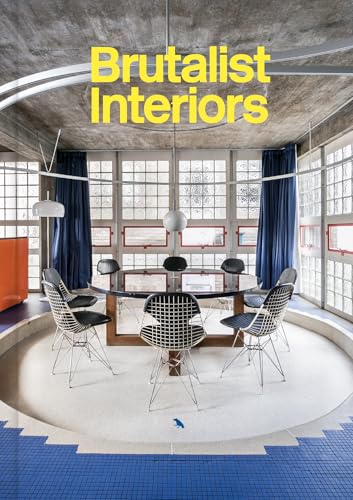

Housden House, Brian Housden, 1963–65, London, United Kingdom

(Image credit: Taran Wilkhu)

W*: What inspired you to create this book?

Derek Lamberton: Brutalist Interiors follows a decade of publishing brutalist architecture maps and books. Visiting buildings featured in these titles is always fascinating, whether in Skopje, Buenos Aires or even here in London. But access to original interiors is rare – and it can be thrilling when the opportunity presents itself. This is what I hope readers find in the book.

Johannes XXIII Church, Heinz Buchmann and Josef Rikus, 1968, Cologne, Germany

(Image credit: Stefano Perego)

W*: What makes a ‘brutalist’ interior?

DL: The vast majority of the interiors included in the book display the movement’s primary characteristics. Think raw concrete, exposed structural elements, and so on. Additionally, I have ended the book with a selection of contemporary interiors. Prefaced by an essay by Felix Torkar in which he elaborates on his term ‘Neobrutalism’, the interiors that follow all reveal the lasting influence of brutalism on interiors today. Some of the more memorable examples here are the Pedro Reyes House in Mexico City and the Shui Cultural Centre in Guizhou.

Pedro Reyes House, Pedro Reyes, 2015, Mexico City, Mexico

(Image credit: Richard Powers)

‘Concrete is not only versatile but it can be made fun’

Derek Lamberton

W*: What is the biggest misconception people have about brutalist interiors or brutalism?

DL: That it is all heavy, dark and grim. I had originally planned to print this book in black and white, but as I researched further, I was energised by both the tonal effect of the concrete interiors and, in juxtaposition, the power of a well-positioned colour feature. This was often as obvious as wooden furnishings or a brass handrail, but also appeared as yellow church organs, purple stained glass or creamy magnolia blossoms through a window. In other words, concrete is not only versatile but it can be made fun.

Sheats–Goldstein Residence, John Lautner, 1963, Los Angeles, CA, USA

(Image credit: Jason Woods)

W*: What is your favourite brutalist building or interior?

DL: Some of the domestic interiors featured in the book are swoon-worthy and might be considered inspirational if you work in a more lucrative profession than publishing. But I’m more drawn to large public buildings – places like the Barbican and Sava Centre – where anyone can wander around with a friend and stumble upon details that encapsulate the era or piece together thematically.

Cafeteria, Saarland University, Walter Schrempf and Otto Herbert Hajek, 1963–70, Saarbrücken, Germany

(Image credit: Marco Kany)

Temple of Monte GrisaAntonio Guacci, Sergio Musmeci, 1965 Trieste, Italy

(Image credit: Roberto Conte)

W*: What surprised you when working on the book? Any new interiors you never knew existed, or anything about them that made you do a double-take?

DL: Over the years, I have rarely, if ever, published colour images of brutalist architecture. Our annual Brutalist Calendar, for example, leans towards more dramatic images with defined shapes and strong shadows. But, when the book’s designer, Jaakko Tuomivaara, and I were arranging the images, I realised there was something almost joyful about this book. It felt like an opportunity to present a different side of brutalism, and hopefully to broaden its appeal as a result.

Barbican Conservatory, Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, 1962–84, London, United Kingdom

(Image credit: Max Colson)

Jaú Bus Station, João Batista Vilanova Artigas, 1975, São Paulo, Brazil

(Image credit: Nelson Kon)

W*: If someone can only visit three brutalist interiors in the world, which are the top three must-sees for a better understanding of the genre?

DL: Ha ha. I like this scenario. Let’s do this person a favour and stretch out their journey as far as possible. I suppose it is only right to begin with Le Corbusier… Let’s start with a trip to Northern India to Chandigarh, where the brutalist interiors of his planned urban centre can be explored sequentially. Then off to Vienna for a spiritual sojourn within the concrete blocks of Wotruba church. And finally, let’s finish things off in a leather lounge chair, feet up, cocktail in hand, in one of Ruy Ohtake’s residences in São Paulo – perhaps the Paulo Chedid Simão House. That should offer plenty to reflect upon as the ice cubes rattle.

Basilica-Cathedral of Our Lady of Altagracia, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Pierre Dupré, 1949–71, Higüey, Dominican Republic

(Image credit: Leonardo Finotti)

BLUE CROW MEDIA

Brutalist Interiors