Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Investments myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Managing investments has three principal parts: deciding which to own, which to ditch and — crucially — implementing those decisions.

Over the years I have heard too many tales of woe from investors who had decided what to do but had not got around to doing it until it was too late.

Many global equity investors will be sitting on decent gains from the rise of the so-called Magnificent Seven stocks. In dollar terms the MSCI All World Index is up over 15 per cent annually over three years. A former colleague used to say that when investors get rich they often think they have become more intelligent.

If they are intelligent, they will be looking nervously at those gains and asking if now is one of those moments to act. For me the best herald of danger is valuation.

Those megacap Mag 7 companies that have driven so much of this growth now make up more than 20 per cent of global equity indices. It’s worth examining which are flashing red on valuations.

The ratio of price to earnings is a crude measure that shows how many years’ earnings it would take to pay for one share. By this measure, it would take nearly two centuries to pay for your Tesla shares.

Earnings — or profits — can be understated if a company is investing heavily for growth, building AI data centres, for example. Looking at the ratio of a company’s share price to its sales gives you a sense of how much these revenues must grow to generate the earnings the share price merits when that capex is done. Few shares trade at more than five times sales for long. Nvidia shares would either have to fall a lot or their sales grow at this speed for many years to come to sustain this valuation.

Revenues are growing strongly in most, but this growth appears to be slowing. AI might improve profitability for a company such as Microsoft — but only if its customers value it sufficiently to merit paying more.

That is a gamble. I am not surprised by recent research showing that 95 per cent of organisations get zero return from their investments in generative AI. On the other hand, the application of AI to diagnostics and factory automation looks like it is raising productivity.

I would not own Nvidia, Tesla or Alphabet now. If I held Apple, I probably would hang on to it as it is not an AI stock and it’s the AI hype I’m trying to avoid.

Beyond these megacap stocks, not everything related to AI is expensive. Taiwan Semiconductor still looks reasonable value, and we bought cyber security specialist Fortinet on its recent stumble.

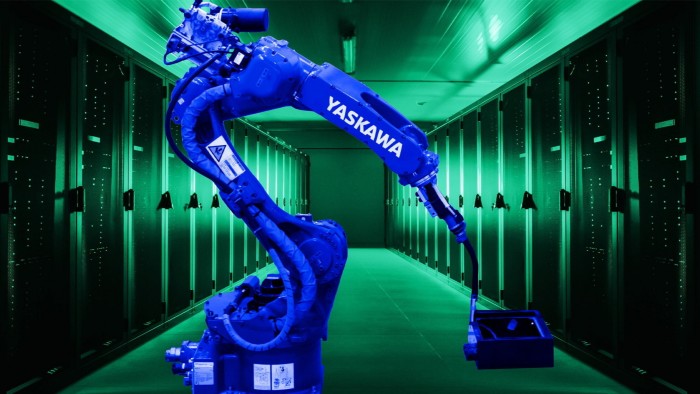

There are still attractive places to have your money. Take Thermo Fisher. This is the world leader in scientific equipment for medical research and diagnostics. It is priced at 21x earnings and 4x sales. Yaskawa makes the blue robots that have the largest share in semiconductor manufacturing and many other areas of factory automation. It is priced at 18x earnings and just 1.5x sales.

Both businesses have seen their growth hampered in recent years by the slowdown in Chinese demand, but this now seems to be moderating and even turning. These are the sorts of companies active fund managers tend to favour.

Those most exposed to the hot stocks are investors in low-cost global equity trackers. These have outperformed most active funds, including my own. They may continue to rise. I have no fear of missing out.

Over the years I have built a record of selling too early. It means my portfolio will underperform the index when it gets frothy, as now. However, my priority is to ensure every investment I have is underpinned by value for money.

I have no idea when a correction might come. I also had no idea in 2000, but we sold most of our tech stocks anyway because the valuations told us to. It was the same selling British banks in 2007, when they were trading on a stretched multiple of book value. You didn’t need to know that a financial crisis was coming, you could avoid the worst of it by being disciplined on valuation, and we did.

No great flare went up at the top to tell you to sell. You just had to follow your investment disciplines and not let timing questions get in the way.

Simon Edelsten is a fund manager at Goshawk Asset Management. Goshawk funds own Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, Thermo, Yaskawa, TSMC and Fortinet