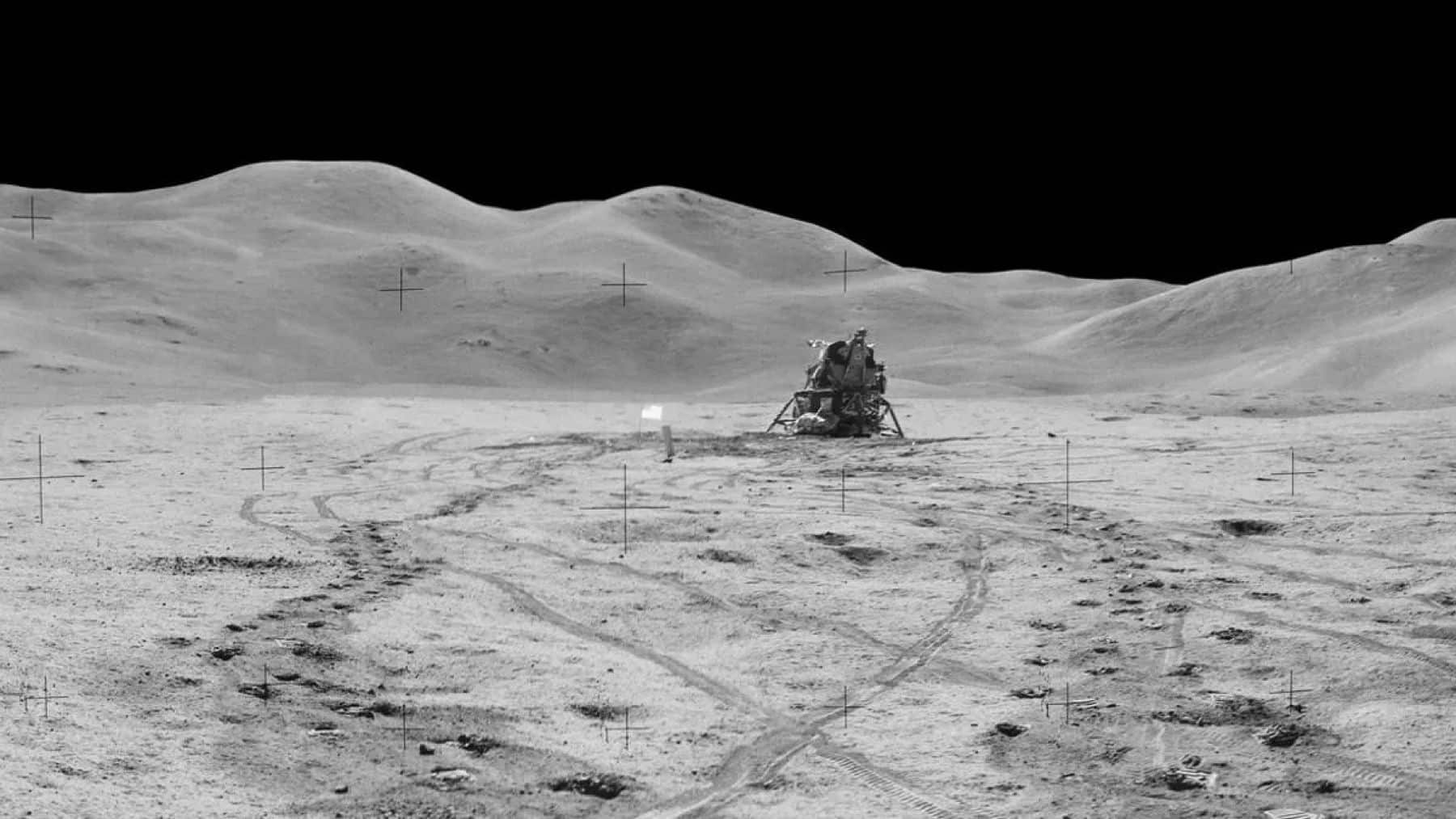

NASA will race China and Russia for a spot on the moon. In the past, the United States was the first – and still the only – country to send astronauts to the moon and have them back. This is one of the most famous moments in history, as Neil Armstrong said the iconic words while walking on the moon. Now, as they are currently trying to return to the natural satellite, they might find more resistance than they previously thought as other nations started to exploring their options to settle where there are no laws: the space.

Race to the moon: countries have the right to explore the satellite

Tensions in space exploration are no longer just about planting flags or collecting samples. The next phase is about building a long-term presence, securing valuable locations, and setting the rules for how future missions will operate. With multiple nations aiming for the same territory, every delay could mean losing strategic ground on the Moon.

Behind the scenes, teams are working on a system that could change how missions survive and operate far from Earth. It’s being designed to withstand the Moon’s extreme conditions, support crews for extended periods, and give its operators a decisive advantage over rivals. The groundwork is nearly complete — and soon, the plans will move from concept to a concrete mission.

NASA authority reveals new plan: nuclear site on the moon

Transportation Secretary and acting NASA Administrator Sean Duffy recently unveiled a plan to put nuclear reactors on the moon—but the announcement had a mixed reception. Critics were quick to weigh in, with NBC calling the plan “impractical, expensive, and dangerous.” For decades, space missions have relied on nuclear materials for power, mostly in the form of radioisotope thermoelectric generators.

These use plutonium-238, which gives off heat that can be converted into electricity for small probes—including some Mars rovers. Usually, this involves just 20 or 30 pounds of material. Some Apollo missions even left small amounts of radioactive power sources on the moon. A full-scale nuclear reactor would require hundreds of pounds of low-enriched uranium in small reactors that haven’t been built yet, carried by launch vehicles that don’t exist.

Small reactors were built to be installed in another place in the solar system

NASA has been exploring the idea of small modular reactors for the moon and Mars for years. According to CNBC, the plan is to fully build and test the facility on Earth before sending it to the moon. Once it reaches orbit, a lander would lower it to the surface, where it would be ready to operate without any further assembly. NASA has made some progress.

But now Duffy wants to speed things up—moving from a modest 10-kilowatt reactor to a 100-kilowatt version, and getting it to the moon by 2030. That’s five years ahead of the timeline Russia and China have announced for similar missions. It’s unlikely that Duffy would pull this off. His 2030 timeline is actually four years later than the 2026 target NASA set just five years ago.

The risks of this project: Canada suffered the consequences of

History shows the risks are real. In 1977, the Soviet Union launched a satellite with a nuclear reactor into low-Earth orbit. Weeks later, the satellite failed. A backup plan to eject the reactor into space didn’t work either. The satellite, carrying over 100 pounds of weapons-grade uranium, plunged back through Earth’s atmosphere, scattering radioactive debris along a 400-mile path in Canada. Cleaning it up took eight months. A similar accident on the moon would be even more catastrophic. If a meteorite damaged a reactor’s cooling system, heat could build up, causing an explosion. That could contaminate a wide area and leave any NASA lunar base without power.

Our coverage of events affecting companies is purely informative and descriptive. Under no circumstances does it seek to promote an opinion or create a trend, nor can it be taken as investment advice or a recommendation of any kind.