Before Lisa Su walks in the room, a flurry of nervous activity unfolds. An assistant scuttles in to place two chilled bottles of her favoured brand of water — Fiji — where she is expected to sit.

A PR handler warns against probing into the personal life of the chief of AMD, America’s third-biggest semiconductor company after Nvidia and Broadcom. “If you start getting one word answers, then … I just want to make sure it’s as productive a discussion as possible,” he says nervously.

In the foyer lurks her mustachioed security guard, a man with arms larger than my thighs. Moments later, the press attaché pops his head back into the room: “She’ll be arriving shortly.”

For all the commotion, Su does not come off as a diva. “Nice to see you,” she says as she walks in, wearing a blue blazer, white trainers, and toting (yet another) bottle of Fiji water. The interview is only one hour; she will not go thirsty.

Su is not exactly warm, but not cold either. Rather, she is serious. A serious woman in a very serious job, the daughter of immigrant parents, an MIT engineer who climbed the greasy pole of corporate America to run what is today one of the most important companies in the world.

In 2022, OpenAI launched ChatGPT and triggered a multitrillion-dollar race to build data centres as the world was suddenly swept up in the artificial intelligence revolution. The critical piece — the brains of these systems — are the meticulously engineered wafers of silicon packed with billions of transistors made by the likes of AMD.

Profits for the first half of the year jumped fivefold to $1.6 billion on $15.1 billion in sales, up 33 per cent on the same period last year. Its surging share price — the stock closed on Friday at $167.76 — pushed its market value to $272 billion. That makes AMD, which employs 29,000 people globally, far larger than Britain’s biggest public company, drugs giant AstraZeneca, and well over double the value of Intel, its stumbling, long-time US rival.

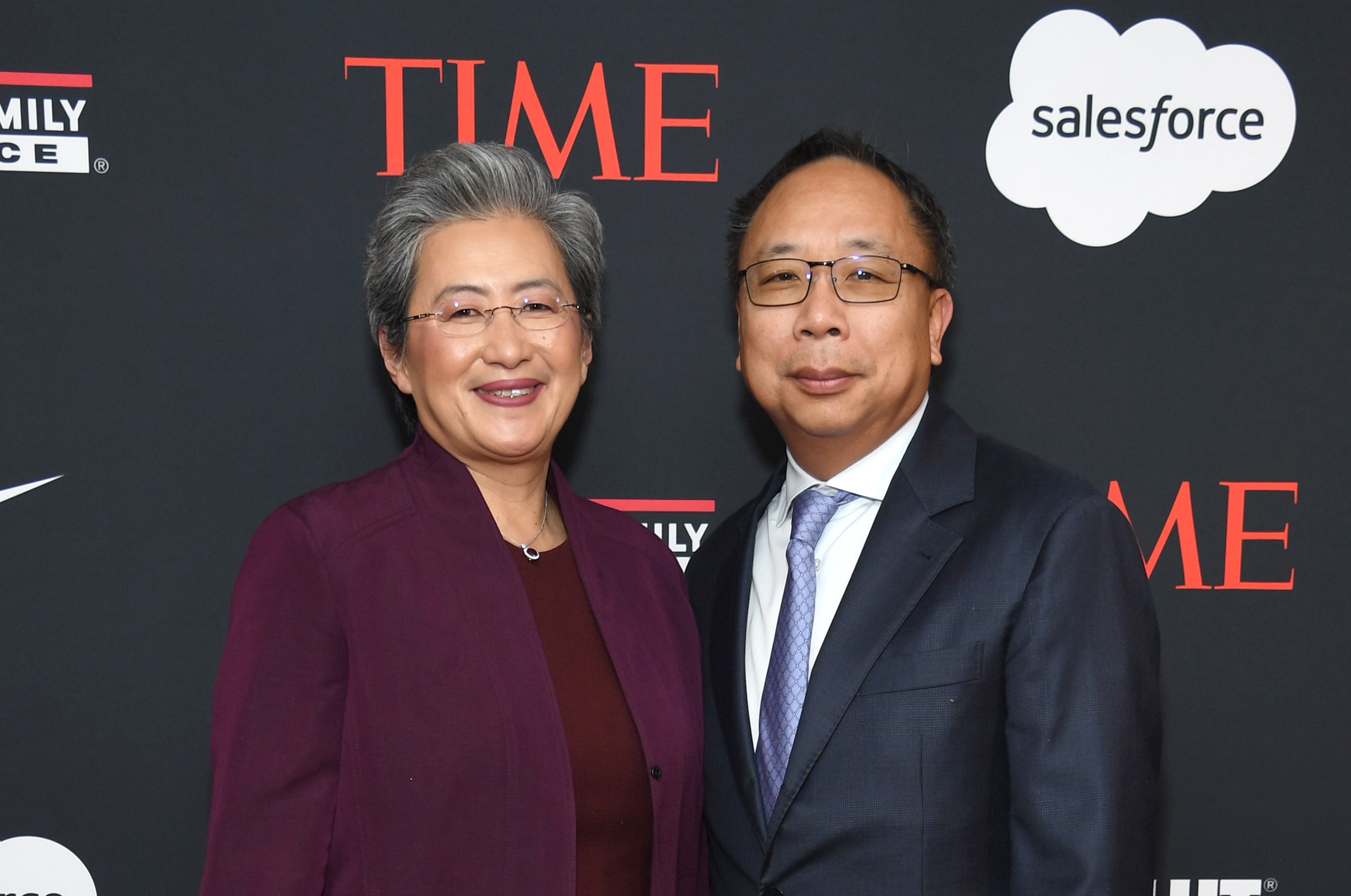

Lisa Su with her husband, Daniel Lin, in New York last year

NOAM GALAI/GETTY IMAGES

AMD is not, of course, Nvidia, the $4.3 trillion behemoth run by Su’s “distant” cousin Jensen Huang — that family relation is another area on which I am told not to tread. But this is the best time to be in the semiconductor business since the dawn of the personal computer — perhaps better. And Su, having executed a decade-long revival of AMD, has put it in prime position to reap the rewards of the AI-ification of everything.

The world wants digital brains, and that is what she is selling.

This moment has also vaulted her, and AMD, to the centre of the geopolitical stage. She and Nvidia’s Huang made news this month when they struck an export deal with President Trump. In exchange for handing a 15 per cent cut of all their China sales to the US government, Trump carved them out of a national security ban that restricted chip sales to China. Did she hammer out that deal personally with The Donald?

“I’m not going to get into all of the back and forth,” she says diplomatically. But it is, “very safe to say”, she adds, that she is spending a lot more time in Washington than she used to. “I actually do believe AI is a race, and it’s a race to intelligence. It’s a race to capability. So every country is now thinking about how do they have their own AI policy and AI plans?”

Critics bashed the profit-sharing arrangement as “crony capitalism.” Su won’t take that bait. “Where do you draw the line of what is national security versus what is, you know, just having more people in your ecosystem. I think we found the right balance.”

Su at a Senate committee hearing about the future of AI in May with Sam Altman of OpenAI, Michael Intrator of CoreWeave and Brad Smith of Microsoft

CHIP SOMODEVILLA/GETTY IMAGES

It must be said that both Nvidia and AMD are selling chips specially designed for the Chinese market with certain computing and memory capabilities “turned off” to make them less powerful.

Beyond politics, however, Su is a techno-optimist. And she is convinced that AI is in the process of fundamentally altering — and improving — the world. In ten years, she predicts, “we will not recognise the world that we’re living in today in terms of the capability that’s out there. And I think that’s a remarkable thing. For all of us who are living in this technology world today, that’s what we live for. We live to build technology that can change the world. And this is uniquely that.”

• Louisa Clarence-Smith: We should be worried that the AI utopia is being shaped by men

More extraordinary than the present moment, though, is the fact that AMD is around to take part in it at all. When Su took over in 2014, the company looked as though it might be breathing its last breaths.

Su arrived in New York from Taiwan aged three. Her father, who had earned a place to study at Columbia University, worked as a statistician. Her mother was an accountant who later became an entrepreneur.

Su and her brother were encouraged to study hard. At MIT, Su chose electrical engineering “because it was the hard thing”, she says. A part-time job at a semiconductor lab “doing grunt work for graduate students” first exposed her to semiconductors. She was instantly hooked. “I was taking little two-inch wafers and putting them in machines and having them do things,” she recalls. “I just thought it was the coolest thing on the face of the planet, that you could build all of this intelligence into these little chips that were the size of a quarter.”

After earning a PhD in electrical engineering, she landed a job first at Texas Instruments and then IBM, where she spent 14 years moving up the ranks. Freescale Semiconductor, a spinout from Motorola, hired her as technology chief before she was poached by AMD in 2012. She was appointed chief executive two years later. “That was a difficult time for the company,” she says.

Founded in the late 1960s about the same time as, and down the road from, Intel, AMD was what one analyst called the “perennial runner-up”. While Intel became the industry standard, AMD pumped out inferior chips. It existed in the mediocre middle. A corporate overhaul by Su’s predecessor was stalling; its market value had sunk to just $3 billion.

Forrest Norrod, head of AMD’s data centre, was Su’s first hire. He recalls: “After I joined, I cannot tell you how many dozens of calls I got with people saying, ‘What the heck did you just do? AMD is irrelevant.’”

Forrest Norrod, head of AMD’s data centre

AMD

An engineer at heart, Su made a few bold moves. She pulled the plug on AMD’s core line of central processing units (CPUs) for data centres and redesigned them from scratch, effectively exiting a market so that it could then re-enter years later with a better product. The revamp, which took years to deliver, paid dividends, allowing AMD to undercut Intel with a new design that was cheaper and better performing. Its chips started gaining share in the markets for laptops as well as data centres, which were booming even before AI, as companies put more of their data in the cloud.

In 2022, the unthinkable happened: AMD leapfrogged the market value of Intel, the company in whose shadow it had operated for half a century. Abhi Talwalkar, a former Intel executive and AMD board director, said one of Su’s strengths is being able to pull people along, even when the ultimate goal seems impossible.

“Great leaders will get the job done, push the team hard, and the team will sign up over and over again, versus leaving a bunch of dead bodies behind,” he says. “She sets a high bar and has high expectations. She pushes people hard, but at the same time, her sleeves are rolled up.”

The results have been remarkable. Since taking over, AMD’s value has grown 55-fold. Thanks to her share options, Su is worth well north of half-a-billion dollars.. The day we meet, she sold a cool $37 million on the market. Her turnaround has been turned into a Harvard Business School case study.

But now the hard work starts. In 2017, she told her engineers to start developing a new line of graphics processing units (GPUs), the specialised chips used mostly in video games, amid early signs that they could be useful for AI systems. She doubled down in 2022, redirecting huge resources to launch a product powerful enough to grab share in the soon-to-boom AI industry. That bet has also paid off. Its data centre operation saw sales nearly double to $12.7 billion last year, driven largely by GPUs.

Su holding an AI processor at a conference in Taiwan last year

ANNABELLE CHIH/GETTY IMAGES

But the mountain in front of her is perhaps taller than the last. Nvidia has more than 90 per cent of the GPU market. Last year it sold $130 billion, a fivefold increase from two years prior.

Su and AMD once again find themselves the underdogs. But the opportunity is vast. AMD reckons the market for AI chips could hit $500 billion by 2028. And having watched her pull off the trick once, Talwalkar is confident she can do it again.

“The company went through a remarkable pivot a number of years ago, directing so much of the company’s attention and resources to AI, to really mount a similar game plan that was executed versus Intel, now versus the big player in AI in Nvidia,” he says. “I think customers are starting to see history repeat itself.”

Time will tell, Su says. “I like to say that the bets that you make in technology, you won’t know for three to five years whether you made the right ones.”

For evidence, she need look no further than her rearview mirror, where Intel is falling further behind. It recently laid off 24,000 people, a fifth of its workforce, and last week faced the ignominy of being partially nationalised by the US government.

Few know as well as Su how quickly the mighty can fall. “Just because you were good yesterday,” she says, “doesn’t mean you’re going to be good tomorrow.”

Su is a fan of Adele’s music

KEVIN MAZUR/GETTY IMAGES