Cy Endfield’s intense African survival adventure purports to teach lessons about the Territorial Imperative and the easy slide to savagery when civilization is far away. Plane-wreck survivors in a remote African desert must fight the local baboon population for food and water. Stuart Whitman, Stanley Baker and Nigel Davenport tempted by the female castaway, Susannah York. It’s certainly realistic, if too insistent in its thesis that humans are No Damn Good. But it will delight nihilistic survivalists.

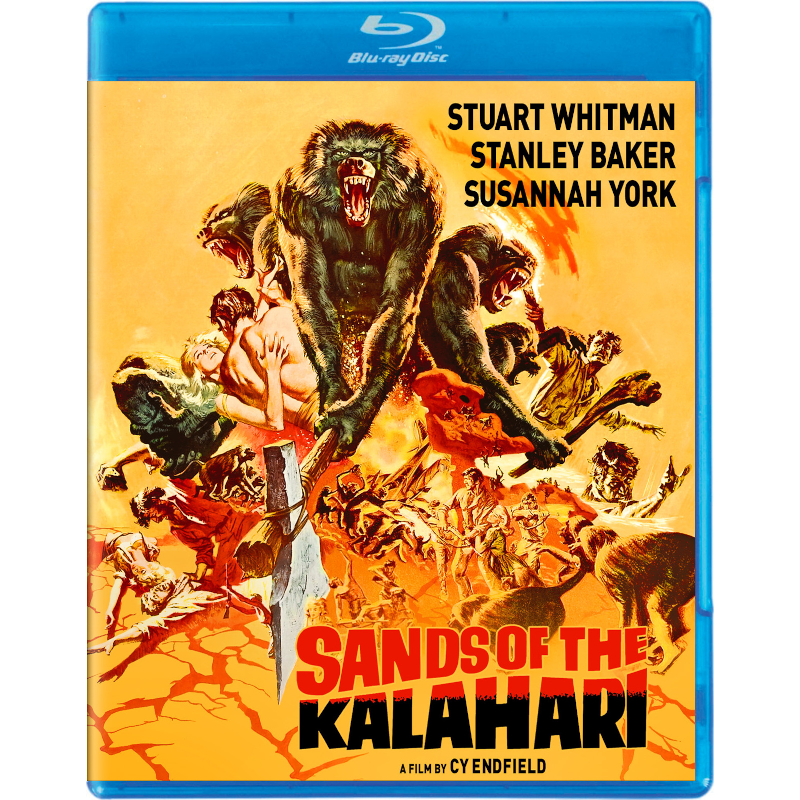

Sands of the Kalahari

Blu-ray

KL Studio Classics

1965 / Color / 2:35 widescreen / 119 min. / Street Date June 17, 2025 / available through Kino Lorber / 29.95

Starring: Stuart Whitman, Stanley Baker, Susannah York, Nigel Davenport, Harry Andrews, Theodore Bikel, Barry Lowe.

Cinematography: Erwin Hillier

Art Directors: Seamus Flannery, George Provis

Special effects: Cliff Richardson, Wally Veevers

Film Editor: John Jympson

Music Composer: John Dankworth

Screenplay Written by Cy Endfield from a novel by William Mulvihill

Executive producer Joseph E. Levine

Produced by Cy Endfield, Stanley Baker

Directed by Cy Endfield

Sands of the Kalahari is a rough picture, unusually brutal and unforgiving for its year, 1965. We’re told it didn’t do well at the box office. In the U.S. it was sold almost like a Hammer film, with ‘shocking’ radio spots that reminded us of the promotions for The Flesh Eaters a year previous. It didn’t sound like a date movie, that’s for sure. The English censors reportedly took a scissors to the violence, which may have hurt its appeal to exploitation audiences.

Writer-director Cy (sometimes Cyril) Endfield was a remarkable Hollywood blacklistee whose career was taken away by the HUAC investigators just before he could establish himself as an A-list talent. Endfield’s final Hollywood movies had been exposé dramas highly critical of the social status quo. The Underworld Story and Try and Get Me! (both 1950) revealed undercurrents of bigotry, racism and lawlessness in a society dominated by the interests of the rich and powerful. Although never a member of the Communist party, Enfield had been active in leftist politics in the 1930s and knew that he would be called before the committee to ‘confess’ and name names. He instead left the country, joining the expatriate ranks of Joseph Losey, Jules Dassin and John Berry.

Relocated to England, Enfield began by directing under false names. In 1956 he worked with young actor Stanley Baker, who wanted very much to start his own production company. Their Diamond Films would produce the 70mm Road Show hit Zulu on an epic scale in South Africa. The partners’ immediate follow-up feature took advantage of their South African experience. William Mulvihill’s novel Sands of the Kalahari put a grimly realistic spin on the oft-told story of plane crash survivors lost in the wilderness. The standard plane crash tale was a small-scale disaster drama, with a passenger list that included a honeymoon couple, a criminal en route to prison, a disillusioned soldier of fortune, etc. The core classic is John Farrow’s 1939 Five Came Back, which builds to a moral, sentimental reckoning on who will fly to safety and who will be left behind.

Endfield and Baker’s Sands of the Kalahari instead proffers a survival ordeal on the boundary between civilization and savagery. The theme was also prominent in two other African adventures of the middle 1960s, Robert Aldrich’s The Flight of the Phoenix and Cornel Wilde’s The Naked Prey. In Endfield’s violent nightmare, the greatest hazard comes from within the downed group of passengers lost in the desert — five men and one young woman.

Inconvenienced by a flight delay, six impatient travelers collectively charter a smaller plane. All goes well until they hit a massive swarm of locusts and are forced down in the Kalahari Desert. One passenger is killed in the rough landing, and the others escape with little more than the clothes on their backs. They are the pilot Sturdevan (Nigel Davenport), retired German soldier Grimmelman (Harry Andrews), friendly Doctor Bondrachai (Theodore Bikel), injured engineer Bain (Stanley Baker), divorced Grace Munkton (Susannah York) and an American hunter, O’Brien (Stuart Whitman). Badly in need of water, the group elects to start walking, and for a while functions as a cooperative unit. They discover that a rocky area is inhabited by a large band of ferocious, intimidating baboons — who have access to a natural spring.

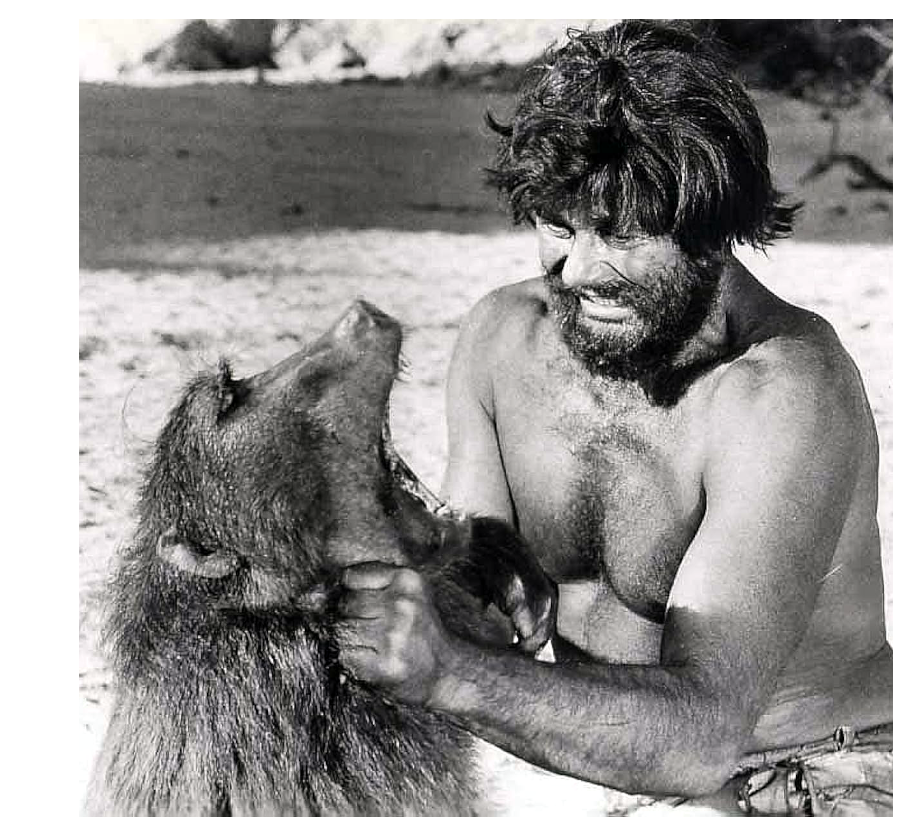

Big game hunter O’Brien has retained his rifle and supply of ammunition. As if taking up a challenge, he strips off his shirt and starts slaying monkeys left and right to establish dominance but also to lessen competition for the food supply. Old Grimmmelman dispenses cautious observations and the Doctor remains cheerful and cooperative. Bain stays silent, watching O’Brien and Sturdevan establish themselves as the he-men of the outfit. When O’Brien brings down an Eland, everybody feasts.

As their hope for a timely rescue fades, the story’s Darwinian outlines come to the fore. Sturdevant suddenly gets it in his head to rape Grace, an event that doesn’t result in the expected further violence. But the disgrace motivates Sturdevant to volunteer to walk out alone to bring help. That leaves O’Brien in charge, and Grace openly gravitates toward him like an animal choosing the fittest biological partner. The arrogant O’Brien does indeed project a ‘most likely to survive’ vibe. He feels empowered to make autocratic decisions for the entire group, and contributes the un-reassuring observation that his personal chances for survival would be better if there were fewer colleagues to feed.

After the positive thrills of Zulu, writer-director Endfield’s Kalahari returns to the unflinching pessimism of his earlier noir thrillers — unpleasant people committing violent, tragic crimes. O’Brien’s Darwinian ruthlessness soon becomes intolerable, serving as a bold critique of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. Given too much authority, egotistical individuals will wreck any society. ‘Anti-social imperatives’ would be the focus of Cornel Wilde’s crude 1970 post-apocalyptic tale No Blade of Grass.

Cy Endfield and cinematographer Erwin Hillier give Sands of the Kalahari a hard, bright surface in Panavision and Technicolor. Everything about the adventure is crisply staged and graphically clear. The thousands of locusts we see clogging the plane’s engines pre-empt the need for a technical explanation for the crash.  Endfield had previously directed Mysterious Island, a much different kind of lost-aircraft adventure. Ray Harryhausen’s fantastic monsters were almost endearing. Here in the Kalahari, Endfield and his crew give us a mob of baboons that brandish frightening dagger-like teeth. →

Endfield had previously directed Mysterious Island, a much different kind of lost-aircraft adventure. Ray Harryhausen’s fantastic monsters were almost endearing. Here in the Kalahari, Endfield and his crew give us a mob of baboons that brandish frightening dagger-like teeth. →

With such impressive baboon footage we wonder why no animal wrangler is credited. There are no phony cutaways to fake docu footage or nature film. These powerful, intelligent monkeys are a constant threat. The baboons seem to wait for an opportunity to retaliate. They tenderly care for their infants. None is disloyal to the tribe, behavior that contrasts strongly with that of the human intruders.

To Endfield’s credit, the extreme survivalist madness is not endorsed. The thesis strains but does not break when Grace elects to passively let the strongest man claim her. O’Brien becomes a modern Tarzan, lording it over the savage animals. What he’s going to do when the cartridges run out, only he can say — he purposely throws himself into dangerous situations, as if craving the thrill of combat and not caring if anybody survives. The repeated image is that of O’Brien running barebacked through the rocks to blast away at his simian foes. The least credible aspect is O’Brien’s skin: under that sun, one would think he would be blistering after only an hour.

The ugly proceedings never seem to let up. Doctor Bondrachai is alone and unarmed when he is confronted by a wary band of Bushmen. When Sturdevan reaches the coast and is ‘rescued,’ he finds out the hard way that his plane crashed in territory set aside for diamond mining, and that anyone caught within the perimeter is presumed to be a smuggler. Brutal company security men proceed to torment him for information. ↑ Back with the other survivors, Bain finally realizes that he must find a way to disarm the murderous O’Brien.

Elements of Kalahari seem to presage more famous directors’ films about the struggle for survival. O’Brien’s standoff against the aggressive baboons on a small outcropping of rock looks very much like the ‘Dawn of Man’ waterhole scene in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, released three years later. Susannah York’s silent response to the desolation of the desert reminds us of Jenny Agutter in Nicolas Roeg’s later Walkabout.

The last thing Cy Endfield offers is a conventional hero or heroine. We’re only given character detail that motivates the narrative; people don’t step up to ‘explain themselves.’ We must decide on our own why Grace behaves as she does, and why Bain remains passive for so long. O’Brien, the man of action, may be Stuart Whitman’s best screen performance. The next year’s An American Dream signaled his descent into less important roles and television work. None of the passengers is a standard type, not even Harry Andrews’ ex-Wehrmacht officer. Theodore Bikel is especially likable as the kind Doctor, an inoffensive fellow who isn’t as helpless as he appears.

When first announced, every film project seems to have tried to attract superstar actors, and when MGM was involved Kalahari announced that Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton were interested. Although dropping out of projects was the norm for the famous acting couple, other cast positions went through abrupt changes as well. George Peppard almost made it to filming, but he and director Endfield didn’t get along. When Peppard left Stanley Baker moved in to play O’Brien, which would have given the producer-star yet another villainous role to play. But Stuart Whitman asked to swap parts, a change that gave the survivor group a much better personality dynamic.

Stanley Baker spent ten years playing cruel, sneering villains, especially in Biblical epics. He’s a great cop in Val Guest’s Hell is a City, but Hollywood’s idea of a breakthrough in a big pictures was a supporting role as a psychotic commando. Baker’s stalwart hero in Zulu was magnificent, but after the failure of Sands of Kalahari he went back to criminals. As a producer he was a positive force in the English film industry.

The movie’s unrelenting negativity can be disconcerting. The U.S. advertising campaign was accompanied by the kind of ‘not recommended for children…’ viewer warnings associated with a horror film, a gambit that would prove successful with Cornel Wilde’s The Naked Prey and Beach Red. A couple of years later, the ‘violence breakthrough’ of Bonnie & Clyde, Point Blank and The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre was enough to ensure the adoption of a ratings system, and the abandonment of the increasingly unworkable Production Code guidelines.

The KL Studio Classics Blu-ray of Sands of the Kalahari is described as a new HD Master from a 4K Scan of the 35mm original camera negative. As such it betters by far Olive Films’ release from 2011. The new disc is sharper overall, with desert textures that emphasize the harsh, clean environment. As noted before, Erwin Hillier’s cinematography is so precise that we wince at a shot of the airplane flying into the sun. John Dankworth’s serviceable score underlines the film’s emotional highlights, especially the grim finale.

A new commentary from Kino regulars Howard S. Berger and Nathaniel Thompson is the main extra. There’s a lot to say about Enfield & Baker’s Diamond Films company, which hit paydirt with Zulu but miscalculated with this one: maybe the filmgoing audience that year just had its fill of cruel negativity.

Viewers with survivalist leanings may relish Kalahari’s ideas about the territorial imperative, and the notion that savagery is always waiting beneath the veneer of civilization. Other audiences will find Cy Endfield’s survivalist ideas to be far too cynical. As far as big lessons learned, my personal takeaway is to always carry Gatorade and to stay away from hostile diamond-country security police.

Reviewed by Glenn Erickson

Sands of the Kalahari

Blu-ray rates:

Movie: Good ++

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements:

Audio commentary by Howard S. Berger and Nathaniel Thompson.

Deaf and Hearing-impaired Friendly? YES; Subtitles: English (feature only)

Packaging: One Blu-ray in Keep case

Reviewed: August 19, 2025

(7380kala)

Visit CineSavant’s Main Column Page

Glenn Erickson answers most reader mail: cinesavant@gmail.com

Text © Copyright 2025 Glenn Erickson