Any country would be lucky to have a vast record of its social and technological history to pass down the generations. Even if its files, put together over a century with public money, were regularly opened up.

The BBC Written Archives Centre was just such a rare trove of information – an accessible public catalogue of British attitudes and habits. But this summer, historians and researchers have been dismayed by moves to permanently alter and limit the available files. Following an audit, the BBC has switched to releasing the contents in an orchestrated way, instead of in response to specific research queries. It claims this is more efficient and offers better value to licence fee payers.

An open letter published this weekend, signed by more than 400 influential writers, researchers and academics, argues the BBC’s decision is sounding the death knell for “independent and exploratory research”.

One signatory, social historian David Kynaston, told The Observer he suspects “a serious scandal is unfolding”, as the old request system is ditched. “It is a terrible situation,” he said. “It is intolerable that a researcher can no longer go in and straightforwardly explain to the excellent archivists that worked there what they are interested in having cleared for their research.”

Scholars who have regularly drawn on the archive are also worried it will now chiefly be used to promote mainstream subjects, providing the public with what the BBC calls “content moments”, tied to key dates or anniversaries. Access to hidden, complex or contested events will be lost, academics fear. Among these threatened narratives, they argue, would be such topics as early coverage of immigration, live jazz recordings or the domestic detail of postwar lives that Kynaston specialises in uncovering.

‘The closing off of its written archive from genuine independent research is a self-inflicted wound that may never heal’

Prof John Wyver

“It may be driven by a squeeze on budgets, but it is a move away from the pure world of the BBC’s founder, John Reith,” said Kynaston, who is finishing work on the latest in his Tales of a New Jerusalem series of books about postwar Britain. “The BBC has public responsibilities.”

But the changes at the archive, held in Caversham, Berkshire, are already under way, despite the growing list of leading academics opposed to them. Access has been reduced from three days a week to two, and inquiries from the general public are closed.

“It is a really important, extensive archive of political and social history,” said Prof John Wyver, a specialist in art on screen at Westminster University. “The BBC has slipped out these revised conditions without asking the academic community. They simply changed the rules.”

He organised the open letter of protest with author Ian Greaves and Dr Kate Murphy of Bournemouth University, who all hope the BBC will think again. Wyver has been cheered by the support the letter has attracted, including from the leading Cambridge historian Peter Mandler. Many who have signed believe the restrictions will now make it difficult for PhD students and authors to research the BBC’s back catalogue.

“They have clearly shifted to it being a resource for BBC business priorities,” said Wyver. “The corporation no longer recognises the value that working with scholars brings, despite the fact this is an archive of how public money was spent over most of a century.”

The BBC argues that its new system will “make a wider selection of BBC history accessible and searchable, with an ambition to open up more of the written archive from 30% to 50% over the next five years”.

A spokesperson said: “Given the level of resource available, we are moving to a series of structured content releases rather than individual requests for specific content, which will open up the written archive further and deliver greater value for licence fee payers.”

Wyver claims the BBC has not explained when the promised extra 20% of files will be released, or what they will include. Fellow campaigner Greaves, whose new book, Penda’s Fen: Scene by Scene, was written after extensive archive research, is also unconvinced. “The BBC is seeking to present a cut to its services as good news for the licence fee-payer,” he said. “The closing off of its written archive from genuine independent and exploratory research is a self-inflicted wound that may never heal. It has been driven through without consultation and in the hope of going unnoticed. It buries the hidden stories that deserve to be heard.” Greaves wants the BBC’s charter, which is up for renewal in December 2027, to enshrine a commitment to restore and protect this “vital national asset, so that the many stories it contains can be told”.

Wyver says much of the external research over the past 30 years that has opened up areas of study, such as Murphy’s work on women at the BBC and Stephen Bourne’s on black artists and production staff, would have been impossible under the new rules.

The BBC said the archive will continue to offer reading room visits and will support legal freedom of information and subject access requests.

My book relied on these records. Keep them open, says Erica Wagner

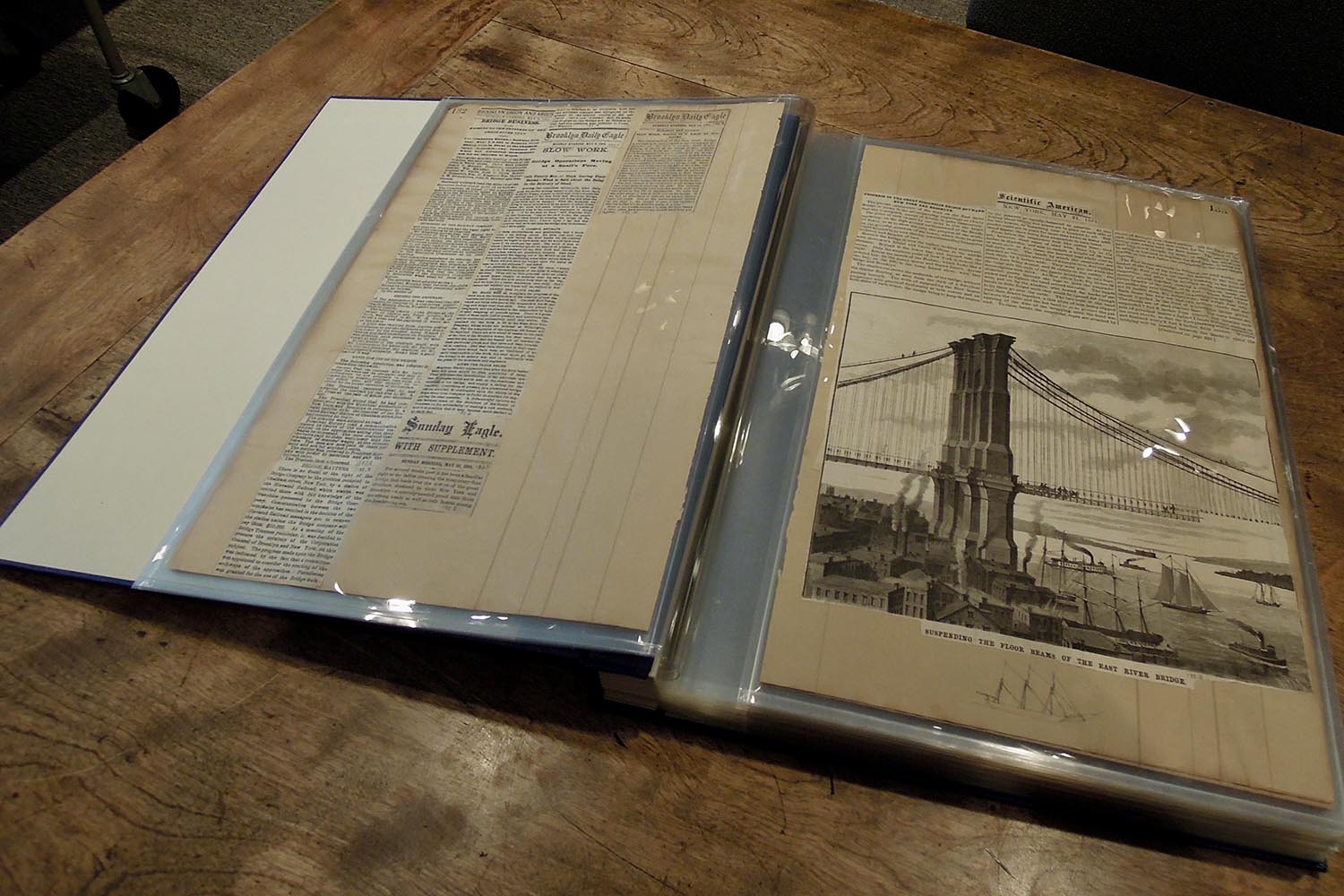

‘Using an archive was the only way I could write my book about Washington Roebling, chief engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge’

As a passionate devotee of the BBC and a lover – and user – of archives, I feel like weeping with despair at our national broadcaster’s statement about its sudden restriction of access to its written archives: “Given the level of resource available, we are moving to a series of structured content releases rather than individual requests for specific content, which will open up the written archive further and deliver greater value for licence fee payers.”

It’s worth explaining how an archive works, because many people don’t have the chance to use them. “Individual requests for specific content” is the whole ballgame. I wrote a book about Washington Roebling, chief engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge; his family’s archive is split between Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in upstate New York and Rutgers University in New Jersey. In order to see these papers , I arranged to visit the archive, made an individual request and was handed a sequence of grey archival boxes, rolls of microfilm and photographs. This was the only way I could write my book. This is what an archive is, and how it functions.

Think about it. “Structured” content releases about the Roebling family (say) would have been no use to me at all. I’d have got slivers of information; I might only have seen what the institution – for whatever reason – wanted me to see. This is no bloody good at all.

An archive is the raw material of history. It is heritage. It is what we need to make sense of who and what we are as we head for an uncertain future. Furthermore, if that archive is the archive of the BBC – the British Broadcasting Corporation, paid for by you and me over the last century – it belongs to us. It is our history. Our heritage. It must not be kept from us.

An archive is history and heritage. We need it to make sense of who and what we are

Believe me, I understand the first part of this shady disclaimer: “Given the level of resource available”. Times are tough. But important decisions must be made as to how available resources are allocated – and how arguments are made for increasing those resources. “Greater value for the licence payer”? Not all value – real value, lasting value – is immediately apparent. Again: that’s the whole darn point of an archive.

The writers and academics who have signed the open letter are right to be alarmed. This is a decision that must be reversed, and fast.

Photograph by Bert Hardy/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images