Research into curing and diagnosing cancers is being delayed for years because international researchers are rejecting job offers in the UK due to high visa costs.

Cancer Research UK told The Observer that several pieces of research had been affected by soaring immigration costs, which have risen by 126% since 2019 and are up to 17 times higher than the average of comparable countries including France, Australia, the US and South Korea.

Analysis of Cancer Research UK’s annual spending on immigration costs shows that the amount the charity has paid the government in visa fees and other surcharges has nearly doubled since 2022-23, rising from £477,244 to £872,044 this year. The money would be enough to train 40 PhD students, according to Dr Iain Foulkes, executive director of research and innovation at Cancer Research UK.

‘High fees are putting off some of the world’s most talented scientists’

Iain Foulkes, Cancer Research UK

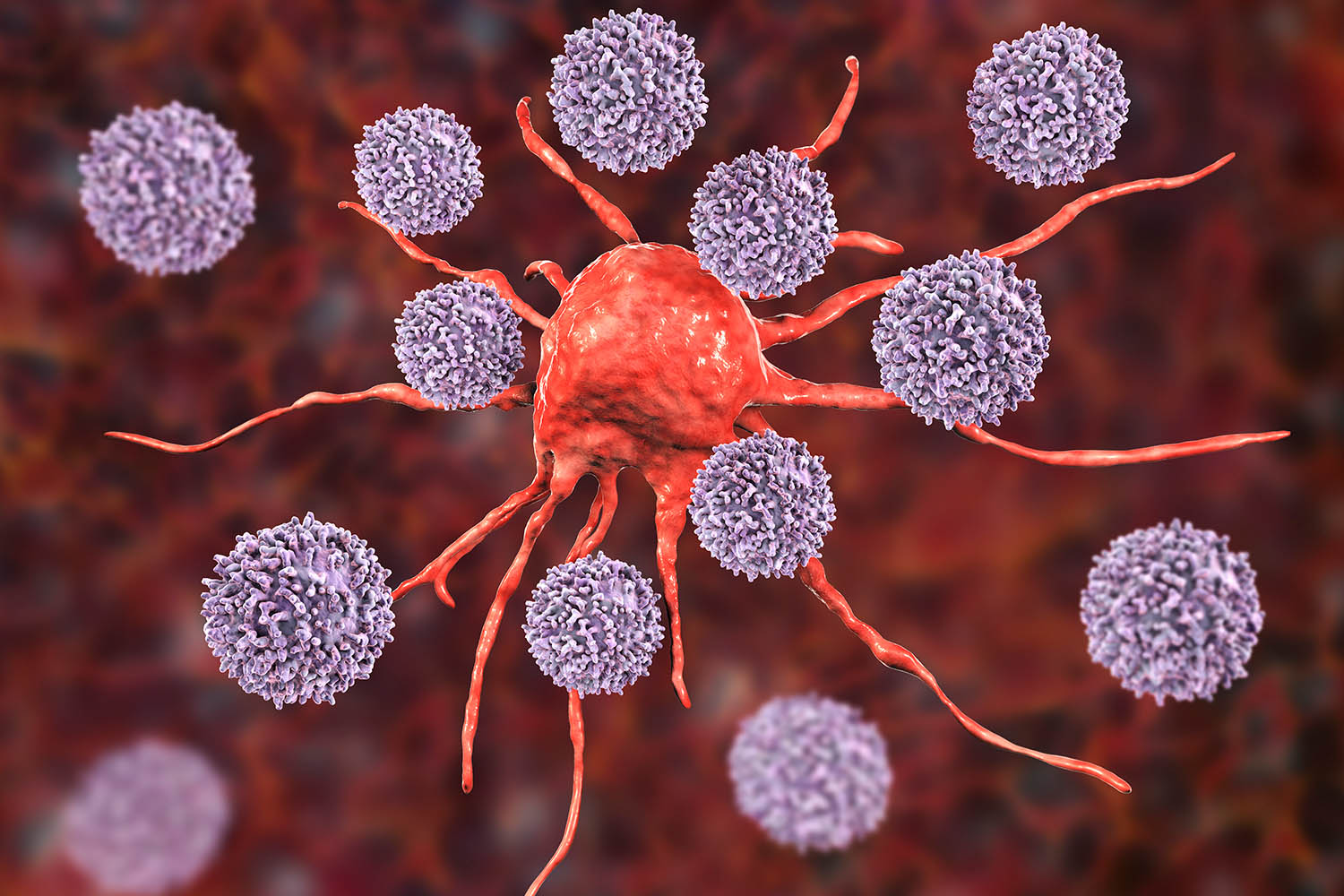

The charity, one of the country’s largest private research funders, was forced to mothball a study in Scotland examining how to encourage a patient’s T-cells to attack colon cancer cells. The results could lead to new immunotherapy treatments to help some of the 44,100 people diagnosed with bowel cancer every year in the UK.

Another study in Manchester, attempting to create liquid biopsies that would enable the early detection of lung cancer, has been delayed by more than six months after a leading researcher turned down a job offer because he could not afford to bring his family to the UK. Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute saw 12 job offers rejected by international candidates in 2024.

Although the charity reimburses candidates once they start work, they need to pay the entire cost of the visa upfront. A researcher arriving on a five-year skilled worker visa would need to pay £6,694, says the charity, and on a five-year global talent visa £5,941. This means scientists with a family of four would need to cover costs of more than £20,000.

“High visa fees are putting off some of the world’s most talented scientists from coming to the UK,” said Foulkes, with “We need to be able to compete for the world’s best scientists.” research institutes forced to divert funds from labs to pay fees.

In May the government published a white paper on immigration aimed at cutting arrivals by 100,000 each year. Polling for British Future found that most people supported using migration policies to address shortages of highly skilled roles. Only 11% of UK adults did not, rising to 23% among Reform voters.

Dr Ed Roberts, a group leader at the Cancer Research UK Scotland Institute, tried to recruit a senior scientific officer in 2022 to work on designing a genetic probe to examine why particular parts of a tumour are vulnerable to a patient’s T-cells. “We had this very well-qualified candidate from Hong Kong,” Roberts said. “The salary was competitive but the visa fees [and] the NHS surcharge gradually eroded what we were offering.

“He said ‘it doesn’t make sense for me to move my family from Hong Kong based on that’. So we had to put out another advert and recruit again.” Eventually the team recruited a researcher from Brazil with no dependants. “Everything just got frozen and put away for a bit more than two years. We’ve now got several probes that are promising, but it is several years after.”

The charity’s National Biomarker Centre in Manchester is looking for ways to diagnose cancer more quickly using fragments of cancer DNA found in the bloodstream. Late diagnosis means treatments such as chemotherapy are less likely to succeed in some cancers.

Scientist remove biological samples from a liquid nitrogen storage tank at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute

Professor Seva Makeev said they had been trying to recruit a bioinformatician, with expertise in computer science and biology, to run analyses of DNA sequencing data. “Every research lab now wants at least one bioinformatician, but supply can’t keep up with demand,” Makeev said.

“We had an outstanding candidate for a bioinformatician position– a leader in the field – and we made the highest possible salary offer we could with the resources available to attract him,” he said. “Yet he declined because he couldn’t afford the visa costs of bringing his family to the UK.”

A government spokesperson said it was “committed to ensuring the UK remains the home for world-leading science and research. The £54m Global Talent Fund will enable leading UK universities and research institutions to attract top researchers and their teams – particularly in high-priority sectors such as life sciences that are central to the modern Industrial Strategy – as part of a wider £115m investment aimed at securing the world’s best scientific and research talent for the UK.

“Visa fees remain under ongoing review and all revenue generated is strictly ringfenced for funding the UK’s migration and borders system.”

Photographs by Science Photo Library/Getty, Dan Kitwood/Getty Images/Cancer Research UK