Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art opened in Gateshead on the stroke of midnight in a blaze of halogen glory one summer night in 2002. The thrill of it shines in memory. The new museum was all bright promise: it was going to be international and yet local; ever-changing but uniquely itself. It was going to bring shows to the north-east before anywhere else, and without any of your London hauteur. It was going to stay free for all – and so it has. Baltic has truly succeeded.

It did not look that way at the start. The transformation of the old flour mill was frustratingly slow, finishing two years after that other brick fortress of contemporary art had already opened in London. Parallels between Baltic and Tate Modern were hard to ignore. Both were industrial buildings, once abandoned on the south side of city rivers but now connected to the north by spectacular Millennium bridges, one swaying over the Thames, the other tilting above the Tyne to let vessels through. Both initially had Swedish directors, who returned home suspiciously fast, and both have internal spaces so vast as to require a certain scale of art.

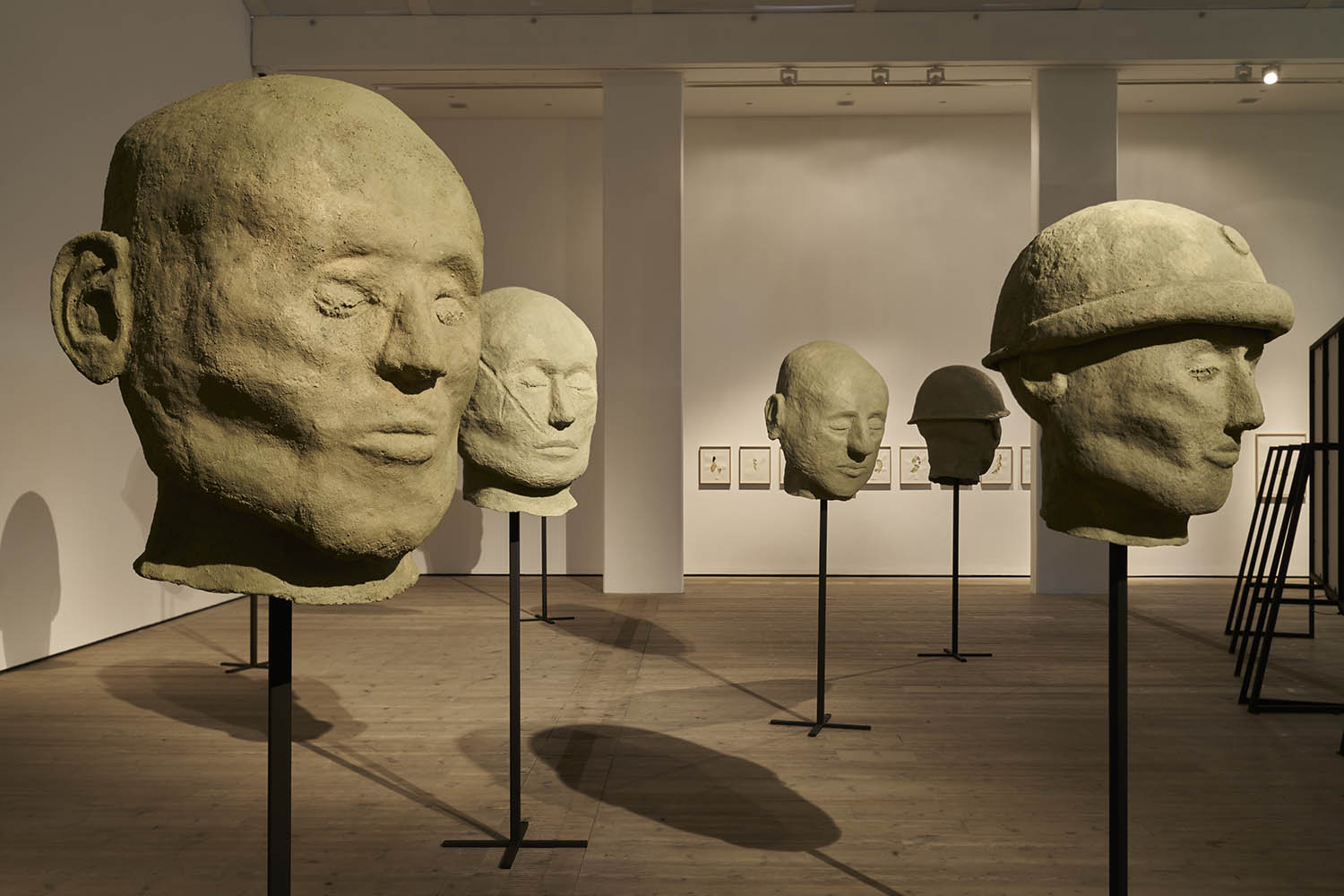

Ali Cherri’s ‘extraordinary sculptural ancient/modern hybrids’ made from mud and legally acquired antiquities

But Baltic is light and airy, its glass-panelled lifts shooting up and down their glass shafts, all the way from the atrium to the 360-degree viewing platform at the very top. Here you can see Tyneside near and far, from swooping hawk to distant spire. Windows on internal staircases offer views into each of the five galleries, stacked above each other, and another platform even allows you to look down into the topmost gallery. At present, this means you can see the work of the Lebanese-born, Paris-based artist Ali Cherri – as never before – from high above.

Cherri won the Silver Lion at the 2022 Venice Biennale for his extraordinary sculptural ancient/modern hybrids. In How I am Monument at Baltic, he is showing monumental figures that appear to be formed from mud – a winged sphinx, a seated goddess, a bird man – each with a carved face of exquisite sophistication. Which is older, the inchoate mud or the subtle carving? The disjuncture (look closely and you can see the glue and stitches) is at the exact faultline of our cultural preconceptions. For it turns out that the mud is contemporary, whereas the faces are legally acquired antiquities.

A winged sphinx, a seated goddess, a bird man. Each is carved with exquisite sophistication

A three-screen film installation shows men making mud bricks in present-day Sudan. Or might this too be the past? The spectacle of hands and feet, water and clay; of moulds, shovels and barrows, the sun beating down and the builders waiting for the wherewithal to dam up water, is both mesmerising – each screen choreographed so that its movements overflow into the next – and appallingly Sisyphean. The longer you watch, the more you sense that somehow all this labour will by stymied by fate; otherwise the old dams of Sudan would survive today.

Cabinets contain what appear to be immaculately crafted wooden buildings: the seats of capital cities, as it seems. Each is in fact a model of the plinth of toppled monuments in Kharkiv, Aleppo and Baghdad. And in Cherri’s central film, The Watchman, a lone Turkish sentry mans the border between the two sides of Cyprus, his eyes red with the exhaustion of watching.

A bird flies into the window; strange lights appear on the horizon; perhaps soldiers are coming. The 26-minute film is extremely gradual, and superbly composed, shot by shot. A study of hallucination, dread and tension, what strikes is its Beckettian circularity. The enemy never arrives.

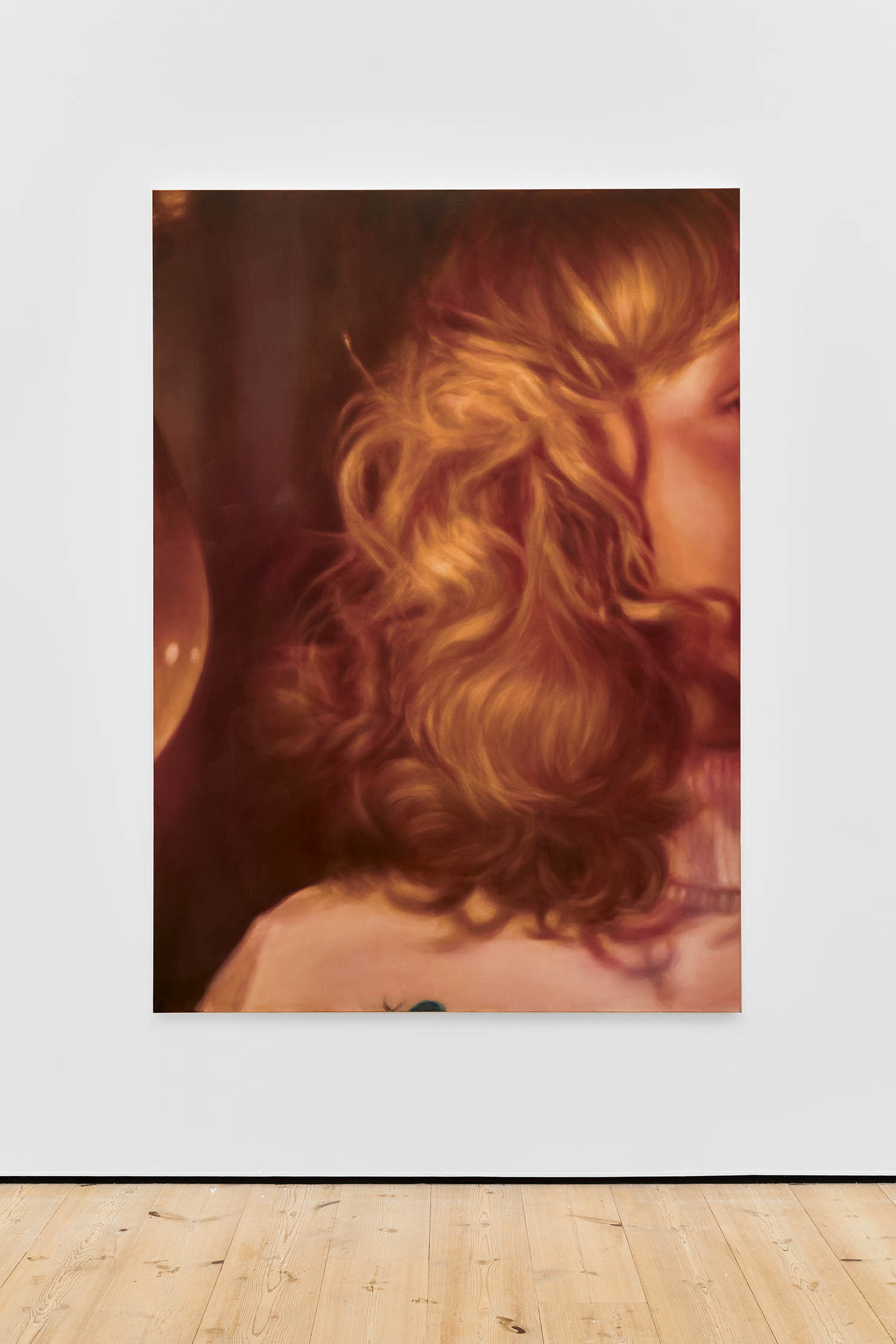

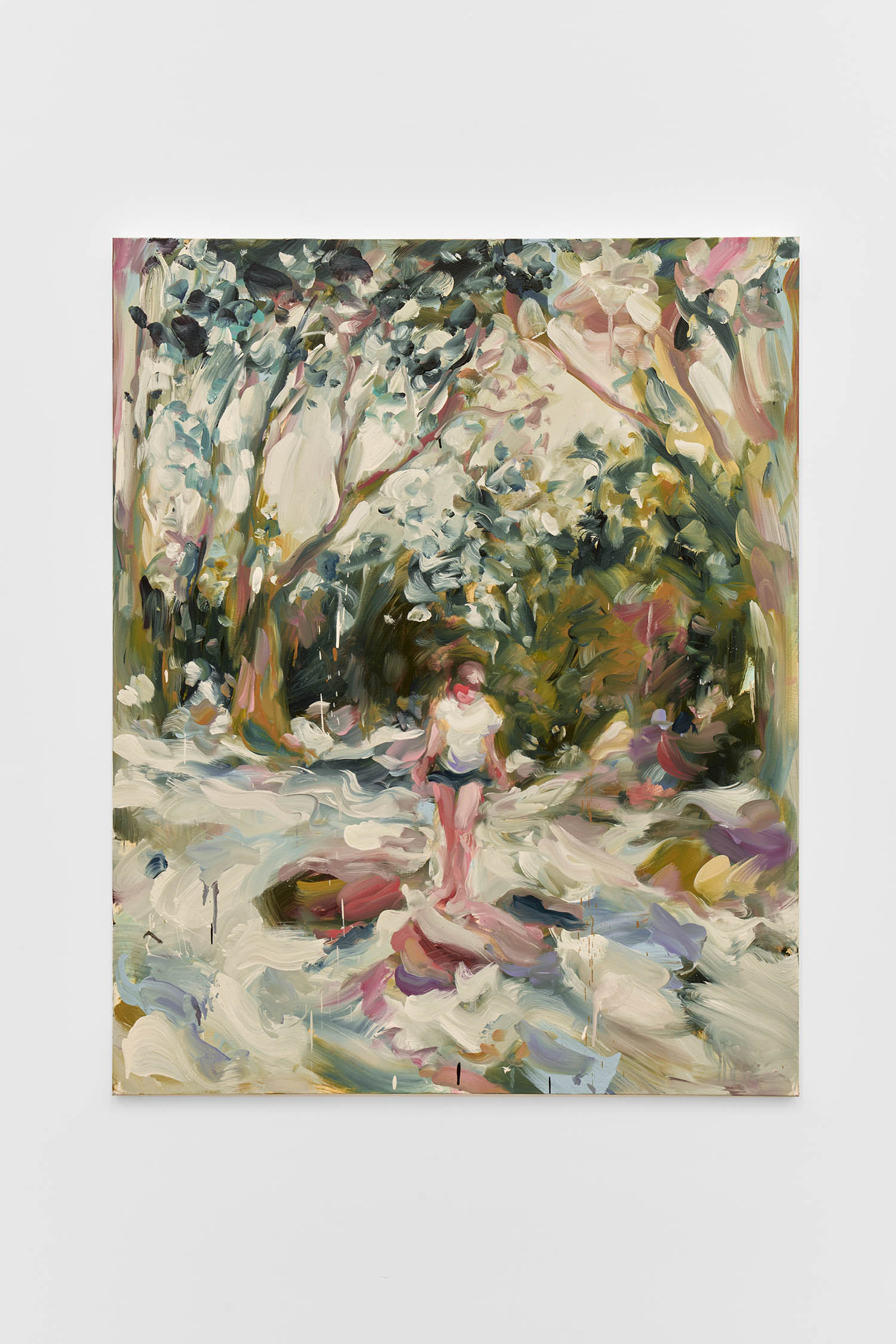

The floor below has enormous paintings by Laura and Rachel Lancaster, twins who share a studio in the nearby Ouseburn area of Newcastle. Each image holds a memory intact – sisters holding hands, a long-ago picnic, sunlight on a woman’s hair – but in different idioms. Laura’s wet-on-wet technique keeps the act of trying to remember in play; Rachel’s transparent smoothness has the gentleness of a hovering vignette.

Rachel Lancaster’s Searcher

‘Each image holds a memory intact’: Laura Lancaster’s Wake Up Dreaming

In another gallery, the brilliantly smart Harold Offeh has taken the Baltic’s famous warmth of welcome yet further with a playscape for children and adults (The Mothership Collective 2.0). Visitors can walk into a sunny yellow film set, and make new sentences, games and visions with a range of media from music to light. One in three children in the north-east grows up in poverty. At Baltic their imaginations can run free.

Mark Wallinger, Ed Kienholz and Judy Chicago, Fiona Tan, Susan Hiller, Jenny Holzer and Yoko Ono (long before Tate Modern): Baltic has presented some terrific shows, with a high proportion of hits against acknowledged duds. It charged nothing to see the 2011 Turner prize exhibition, unlike Tate Britain (£14 last year). To help keep it free, Wallsend-born Sting recently made a huge donation to its new endowment campaign and will perform at October’s fundraising gala.

Baltic has no permanent collection and survives by a constant rotation of exhibitions. If you don’t care for one, you might like the art on a different floor. This takes the pressure off expectation and encourages roving curiosity, up and down the building from one ticketless show to another. I have never had a bad time at Baltic down the years, but I have had plenty at Tate Modern.

Harold Offeh: Mmm Gotta Try a Little Harder, It Could Be Sweet is at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, from 15 November 2025 to 1 March 2026. His Mothership Collective 2.0 runs at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art until 1 February 2026

Ali Cherri: How I am Monument and Laura Lancaster and Rachel Lancaster: Remember, Somewhere are at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art until 12 October

Photographs courtesy of Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art