As one of the foremost architectural historians of his generation, Andrew Saint presented an unflinching view of the practitioners who touch all lives with all their noble intentions and human foibles. Unpicking the vaunted reputations of the great architects in books such as The Image of the Architect (1983), Saint channelled the vanity, pretentiousness and arrogance, as well as the brilliance, with the cautionary rider that “the powers, attributes and aims assumed by architects have often been at odds with reality”.

Edwin Lutyens was therefore “the foremost natural talent English architecture ever produced. His buildings were better conceived than Wren’s or Adam’s and better made than those of Frank Lloyd Wright (an admirer). Against modernist barbarities, they say, Lutyens held up the banner of humanism”. There was always a but. “Part of the trouble is that Lutyens resists intellectualisation. His buildings were seldom about ideas that could be put into words. Lutyens was among the last architects who built for a set. The sentimentality and rootlessness of the Edwardian classes whom he served is mirrored in the brittle brilliance of the villas (seldom landed country houses) he created for them.”

Of James Stirling, who gave his name to the Riba annual prize for Britain’s best new building, he said: “Architects love him, while those who use his most notorious buildings loathe him. Today when engineers can twist structures to any shape an architect likes, it’s hard to recreate the impact made by the Leicester Engineering Building in 1962. Hitherto most modern British architecture had been dour, colourless and rectangular. Here it went wild. It is a tumultuous, exuberant performance, sometimes comic, sometimes perverse.” And yet, according to Saint, its utility was undermined by “a hard-driving, hard-drinking womaniser, a mixture of brutal and sensitive, kindly and selfish, greedy and funny. He had all the charm and confidence that architects must have to win jobs, but lacked any grain of social sensibility. His goal was to be a great architect, and sod almost everything else. In short he was a charismatic monster, as artists often are”.

The Engineering Building at the University of Leicester, above and below

ALAMY

Of the German-American founder of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, he said: “A period of eclipse often overtakes those whose ideas have become familiar to the point of cliché, but have yet to be detached from us by the processes of history. Gropius is certainly suffering from such a phase. In the air of bitterness and resentment still informing criticism of the Modern Movement, the most persistent theorist and organiser of its heyday has reaped his due share of derision.”

Tall and bespectacled with scholarly, bushy eyebrows, Saint looked not unlike the traditional Anglican clergyman that his father was. One might have been forgiven for thinking that he was about to deliver a sermon and he could give the impression of intellectual austerity on first encounter. Yet his young fogeyism was a front for a hinterland of fun and frivolity that would burst forth on better acquaintance. An invitation to collaborate with Saint would be a voyage of rigour around his beetling longhand and pinpoint-accurate notes. His friend Gillian Darley, the architectural historian, said that being in Saint’s company “always involved an exchange of recent reading, a dash of gossip and exasperation at yet another misstep by a familiar institution or bureaucracy”.

Friends would be treated to tours of hidden London, particularly Victorian treasures south of the Thames such as at Brockwell Park or Streatham Common. If there was a characterful old pub in the vicinity to end the excursion with a foaming pint of ale, so much the better. He had a wide circle of friends, many of them with interests far removed from his own, and he was, one friend recalls, “always interested in what made people tick”.

Andrew John Saint was born in Shrewsbury in 1946, one of two children to the Rev AJM Saint and Elisabeth (née Butterfield). His father was the vicar of St Philip and St James, Oxford, a grade I listed gothic revival masterpiece by George Edmund Street that helped to inspire Saint’s love of buildings.

After education at Christ’s Hospital in West Sussex, Saint remained unrepentantly bookish at Balliol College, Oxford, while all about him were growing their hair. And rather than listen to blues or rock at student hops, he contented himself with playing the cello to a high standard in trios and quartets.

He remained unstirred by the radicalism of the University of Essex in three years as a young lecturer there from 1971. He was appointed architectural editor of the Survey of London for 12 years from 1974.

Aged 30, he cemented his reputation with a fine study of the Victorian architect Richard Norman Shaw, whose buildings included New Scotland Yard and the Piccadilly Hotel on Regent Street. John Betjeman was among the book’s admirers. In 1986 the Survey of London was shifted from the auspices of the Greater London Council — on its abolition by Margaret Thatcher — to English Heritage (now Historic England), where Saint remained for the next nine years.

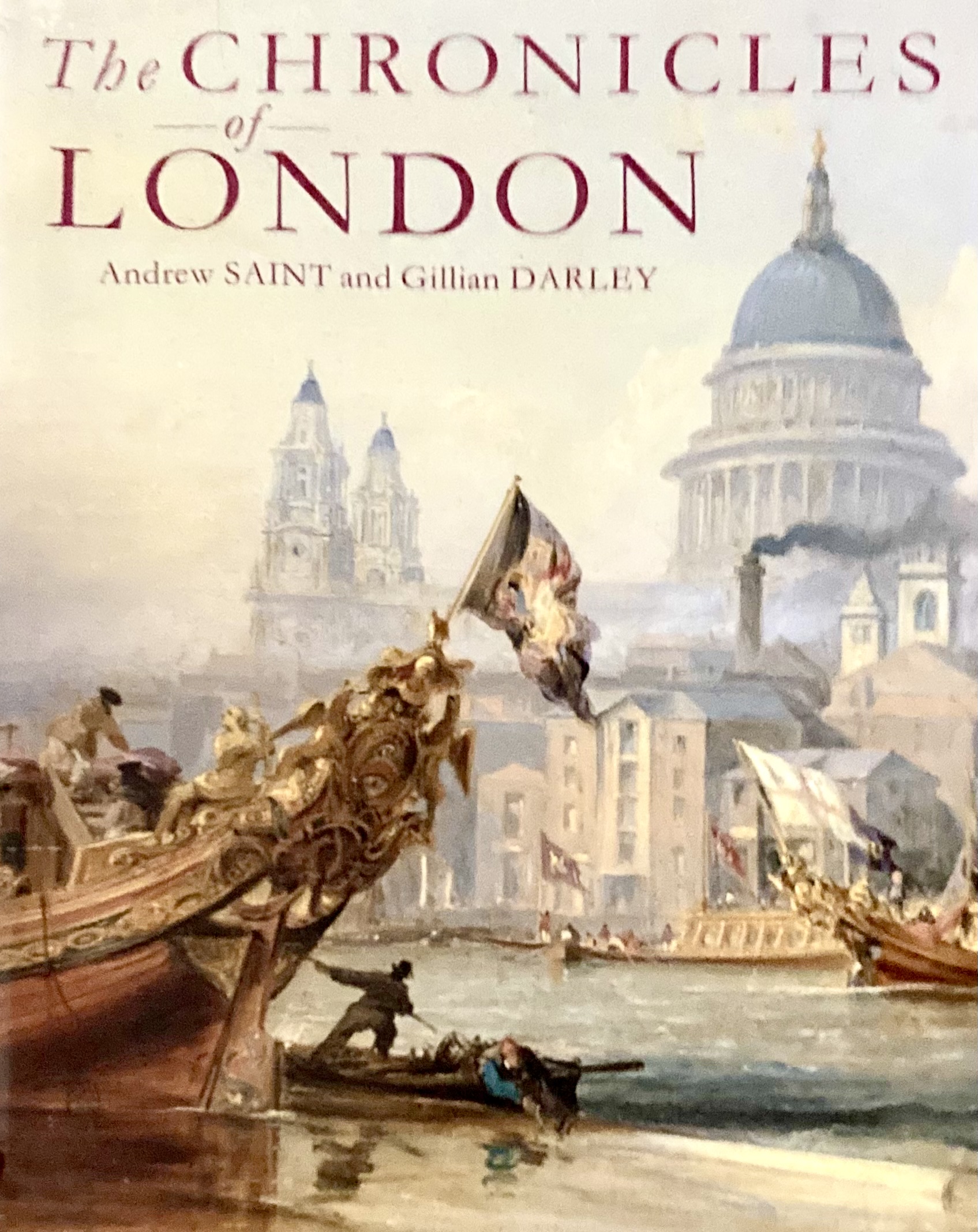

One of his works published in 1994

Canonisation of sorts, in an academic milieu, was conferred on Saint in 1995 when he took up a professorship at Cambridge University to teach architectural history. He taught his doctoral students that if they must be orthodox in their appreciation of the modern movement, then not to be dogmatic and never to ape the architect’s cardinal sin of using pretentious, meaningless language. Prose should be clear and accessible: he never bought into the high-handed attitude that if you don’t understand you’re not clever enough.

And if he never felt that he had quite found his spiritual home, he fought on the front line against attempts to close the department in the late Noughties as an act of academic vandalism based on flawed research. He did not wish for a fellowship and continued to live in London, in a terraced house on a crescent in Kennington, south London. Built in 1913, it was an artisan’s cottage resplendent in red brick and gabled windows.

Despite being steeped in historicism as a doyen of the Victorian Society, and a general evangeliser of the merits of that’s century’s buildings, Saint wrote one of his best books — Not Buildings but a Method of Building — The Achievement of the Post-War Hertfordshire School Building Programme (1990) — on the architects at Hertfordshire county council in the Fifties and Sixties who revolutionised postwar school building and architecture in general with a humanist vision of modernism. Saint wrote a compelling narrative of how Britain’s baby-booming population, a severe shortage of labour and materials after the Second World War and progressive educationists were the mother of invention in use of materials and flexible, modular system-based building concepts.

Yet London, a place he dearly loved and understood instinctively, remained his specialism. Returning to the Survey of London in 2006 to take up the position of general editor, Saint tried to remain true to the socially reforming roots of CR Ashbee, who had founded the Survey in 1894 to record the historic fabric of the capital. He safeguarded the Survey’s future when it was under threat and oversaw its move from English Heritage to University College London and Yale.

Saint made it his mission to oversee works on the West End of London, which had been surprisingly neglected by the survey, such as two volumes on Marylebone (2017) after securing funding from the Howard de Walden Estate, which owns much of the high street. He added other volumes on Oxford Street (2020), Battersea and Woolwich, the first of which was written entirely by Saint and praised for its detail and elegance — it sold out.

He retired in 2019, but never from the pen. Two years later he published London 1870-1914: A City at its Zenith, which according to one reviewer was “enlivened with a rich line-up of colourful characters, including Baron Albert Grant; Henry Mayers Hyndman and his connections with Karl Marx, William Morris and George Bernard Shaw; John Burns; Octavia Hill; Aubrey Beardsley and the artistic bohemians”. He wrote to the end. His final book, Waterloo Bridge and London River: Investigations and Reflections, will be published posthumously later this year.

Saint is survived by his two daughters, Catherine and Lily, from his relationship to Ellen Leopold, a fellow author and “radical”, and a third daughter, Leonora, from another relationship. After his separation from Leopold his long-term partner was Ida Jager, who also survives him.

He never tired of recording the rapidly changing city of London. He did not buy into the idea that the capital was properly planned, but that it was a series of villages. Within 10km of Trafalgar Square there is “something that binds the fabric of London together in a loose but definite way” — a feeling strengthened by the vernacular character of the London terrace. Saint said in 2021: “I’ve been living in London for 50 years now and I have no plans to leave, despite Brexit, Covid, the desertion of a few old friends to the countryside and a rash of absolutely dreadful new tall buildings. Its secrets are more various than other European cities.”

Architecture was endlessly compelling, he said, because it was one of the few disciplines that was both a science and an art in hopefully equal measure. “If you treat it just as science, you will be ignored. If you treat it just as art, it may well pay you back.”

Andrew Saint, architectural historian, was born on November 30, 1946. He died after a long illness on July 16, 2025, aged 78