The High Court has recently considered whether an exchange of

WhatsApp messages can create a contract.

Jaevee Homes v Fincham [2025] EWHC 942

(TCC) arose from a dispute between a property

developer, Jaevee Homes Limited (“the developer”), and

demolition contractor Mr Steve Fincham (“Steve”)

regarding the terms of a construction contract.

The parties had agreed that Steve would carry out demolition

work, but they disagreed over the terms of their agreement. They

had started negotiating via email and then moved to WhatsApp

messages. Steve argued that a sub-contract with the developer was

formed by this exchange of WhatsApp messages. The developer

countered that a sub-contract had been agreed based on its standard

terms of business, having sent Steve these standard terms after the

WhatsApp exchange but before Steve started work.

Steve started the demolition work on 30 May 2023 and completed

it by July. The developer failed to pay any of his four invoices in

full. Following a disagreement over the amount of work Steve had

completed, the developer purported to terminate the sub-contract

that was (supposedly) based on its standard terms of business. The

developer also argued that the four invoices Steve had submitted

– on 9 June, 23 June, 14 July and 27 July 2023, totalling

almost £200,000 + VAT – did not comply with its

standard terms of business and were therefore invalid.

After a complex background of legal proceedings, the dispute

ended up for consideration before Judge Roger ter Haar in the High

Court.

How was a contract formed?

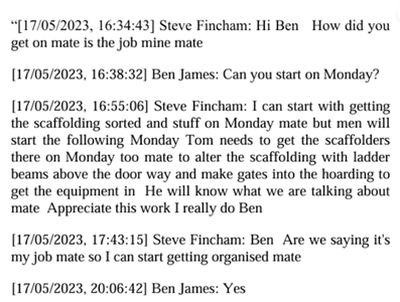

Judge ter Haar found that the parties had agreed a contract by

the following exchange of WhatsApp messages:

The judge said that this exchange, “whilst informal,

evidenced and constituted a concluded contract”. There was by

this point clear agreement on the identities of the parties, on the

scope of the works that Steve was to perform and on the price.

These being sufficient to bring a contract into existence, the

developer’s reply “Yes” brought a contract into

existence.

The judge went on to find that the parties had also agreed

payment terms (monthly payment applications using invoices) but

that this was not essential to create a contract. And, if the

parties had not considered the payment terms, legislation would in

any event have implied payment terms into the sub-contract, it

being a construction contract (on which, see below).

The developer had argued that there was no agreement on the

duration of the works. The judge commented that this was not

essential to form a contract, noting that the law implies a term

that the contractor will complete their work within a reasonable

time.

The developer had also complained that no start date had been

agreed. The judge said that a precise start date was not “an

essential term of the contract”. It was therefore not needed

to create a binding sub-contract.

Peculiarities of construction contracts

In isolation, this case may not seem especially noteworthy. It

is well established that contracts can be concluded without much

formality. Provided the usual tests are met (clearly identified

parties, agreement on what is to be done, consideration such as a

promise to pay a price, an intention to create legal relations and

sufficiently certain material terms), there is no legal principle

against concluding a contract through WhatsApp messages.

However, this case is particularly interesting for businesses

involved in the construction sector. It highlights the significance

of the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996

(“the Construction Act”). Just as the Consumer Rights Act

2015 implies terms into consumer contracts – such as that

goods sold must be of satisfactory quality and as described –

that are not necessarily in the parties’ minds when concluding

a consumer contract, so the Construction Act implies important

terms into construction contracts. Many terms.

Part II of the Construction Act defines what a

“construction contract” is. This is broader than you

might expect. It encompasses, not just stereotypical building work,

but also professional services (such as landscape design) and a

plethora of other activities, such as painting or the fitting of

air conditioning – except contracts with residential

occupiers.

Until 2011, “construction contracts” had to be in

writing. That is no longer the case. Now, even oral construction

contracts, such as Steve’s sub-contract, are captured by the

Construction Act.

The Construction Act implies a unique right to refer disputes to

an adjudicator. This is the right that Steve used to bring a

– successful – adjudication against the developer to

enforce his four payment applications, which the developer then

sought to challenge in the High Court, including before Judge ter

Haar.

Adjudication, which applies only to construction contracts (and

to other forms of contract where parties have expressly opted in),

is a rapid and (compared to litigation in the courts) low-cost

method of resolving disputes. Each party must pay its own costs and

the process is widely regarded as effective. Very rarely do courts

allow appeals from adjudicators’ decisions. Instead of a judge

deciding the dispute by following the courts’ usual slow

timescales, an independent adjudicator reaches a decision within

weeks of a dispute being referred to them. Adjudicators are often

construction professionals such as quantity surveyors, rather than

lawyers.

If a construction contract does not contain written provisions

regulating the adjudication process – such as oral contracts

and Steve’s WhatsApp contract – rules are implied by the

Scheme for Construction Contracts (England and Wales) Regulations

1998 (“the Scheme”). Additionally, the Construction Act

tightly regulates payments in construction contracts. Where parties

do not expressly agree payment terms, comprehensive terms are

implied by the Scheme.

In Steve’s case, the developer had sought to argue that no

contract could have been formed by the exchange of WhatsApp

messages because of an (alleged) absence of terms regulating the

payment process, and that instead its standard terms of business

applied. Because Steve had not complied with the stringent payment

provisions of those standard terms, this argument would have

allowed the developer to set aside the payment applications that

Steve had enforced via adjudication.

The judge dismissed the developer’s arguments, noting that

comprehensive payment terms are implied by the Scheme and that

Steve, in making payment applications by issuing his invoices, had

complied with those implied terms. Therefore, three of Steve’s

four payment applications were valid. (The fourth was invalid

because Steve had made two applications that month, and the judge

found that the parties had agreed in their WhatsApp messages that a

maximum of one payment application would be made in any monthly

payment cycle. Notwithstanding this, Steve was the successful party

overall, having succeeded on every other point.)

What does this case mean for you?

This case provides a timely reminder of the ease with which

contracts can be created. In the construction sector and other

areas with complex legislation, such as the processing of personal

data, these can automatically be subject to a wide range of

unfamiliar terms and processes.

As a business, it is important to make sure that you know when

you have formed a contract. To avoid creating contracts

unexpectedly:

- ensure that, wherever possible, your staff use work emails and

not social media channels - make sure all communications – both written and oral

– are stated to be “subject to contract” - require your staff to document business arrangements properly

and refer all new relationships through your business’ legal

team - where you intend to conclude a contract, ensure that you

formalise its terms and conditions in writing, and include an

“entire agreement” clause that prevents pre-contract

negotiations and communications from influencing the contract’s

terms - if your business operates in sectors such as IT or construction

where it is common practice to start some work before the final

contract has been fully agreed, use letters of intent or similar

such arrangements to formalise the terms that apply to those

initial services before the final contract is agreed and

signed.

If in doubt – and particularly if a new contract might be

a construction contract and you are unfamiliar with the

Construction Act’s requirements – seek legal advice. At

Lewis Silkin, we have experts in construction law, data law and a

plethora of other areas. They are ready to help your business

comply with the law’s requirements and avoid costly

mistakes.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.