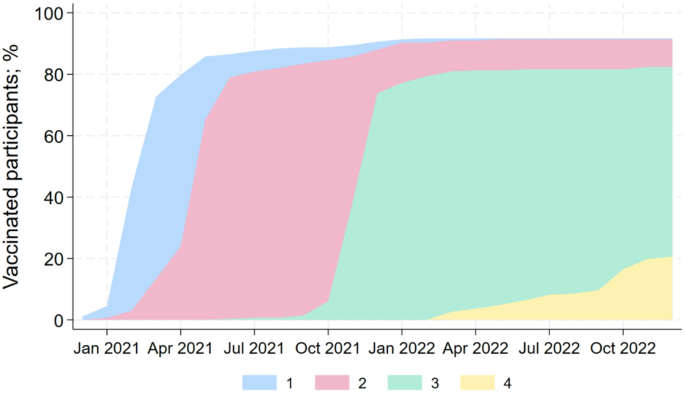

Vaccination rates among the dental team members in Germany were much higher than in the general population. The vaccination rate in the dental team was very high, 82% of the team had at least 3 vaccinations. By contrast, by April 2023 62.6% of the German population had been vaccinated twice and only 15.2% had been vaccinated three times25.

The dental team witnessed a turning point in March-April 2020 after the outbreak of the pandemic. Forced closure and shortage of personal protective equipment caused fear and anxiety among dental teams and their patients26. Authorization of the first vaccine promised a milder course of disease and enhanced protection from future infection27. This achievement was embraced with optimism, offering a relief in time of uncertainty. Despite emerging reports of serious side effects following vaccine administration, dentists and their teams were not reluctant to follow the recommendations of national and international health agencies28. The acceptance rate of the COVID vaccine varied greatly across countries (33-97.5%), showing a significant positive association between country income and vaccine acceptance29,30. Other studies suggest that the intention to be vaccinated is correlated with the perceived risk of infection31. Globally, the perceived risk of infection among dental healthcare personnel was extremely high32,33, which explains the notably high percentage of vaccination rate among our sample compared to the general population.

In our sample, we noticed a slightly higher vaccination rate among dentists (95.5%) compared to 84.2% among dental auxiliary personnel. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers is a known complicated multidimensional matter. In Europe, previous research has shown that low socioeconomic status has been a significant obstacle to vaccination against various diseases34,35. Additionally, an access to scientifically accurate and up-to-date vaccine information leads to a positive attitude towards vaccination36. Our results align with various studies that reported higher vaccination rates among general practitioners and dentists compared to nurses and dental assistants37. Although there is not a definite explanation for this phenomenon, several factors may contribute to the differences between these two crucial occupational groups. We presume that a lower socioeconomic status, less vaccination literacy, adverse influence by media coverage, and less trust in pharmaceutical industry / health authorities might be possible explanations for the lower vaccination rates among dental auxiliary personnel.

Unfortunately, there are multiple definitions for long COVID, varying in their time frame for symptoms onset and duration. The WHO defines long COVID symptoms lasting for at least 2 months11, whereas the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) requires symptoms to be present for at least 3 months38. However, neither organization specifies the nature or number of symptoms required to make a diagnosis. Based on extensive follow-up studies conducted since the outbreak of the pandemic, researchers have compiled a list of over 200 symptoms observed in patients suffering from long COVID39. The broad definition of long COVID on one hand and the lack of a specific biomarker or exclusive symptoms on the other hand, poses a challenge for establishing a consensus in research approaches. This variability makes the comparability and generalization of results across different studies particularly difficult. Symptoms of long COVID may resolve over a period of months for most patients or can persist for years40. A limitation to our results is that we do not know if our participants have a confirmed medical diagnosis for long COVID or if they fit the global definition. However, our results align with published research examining common long COVID symptoms. Fatigue and exhaustion are the most frequently reported symptoms in our sample (Table 2), leading in almost 40% of the cases to a decrease in daily activities. Interestingly, those symptoms were more pronounced among dental assistants than among dentists. Furthermore, 7 out of 32 (21.9%) participants reported reducing working hours due to long COVID. Several studies have discussed the association between employment status and sickness presenteeism (going to work while being ill)41. In the pandemic era, the number of sick notes increased and sick notes were more frequently issued to people with a COVID-19 infection than those without, even in times when most people were already vaccinated42. Considering those findings, we can only assume that auxiliary team members tend to take longer to return to work whilst the owner of the practice might return earlier to work.

Reported incidence of long COVID varies greatly (8–35%)14,39. Those variation can be attributed to several factors including definition of long COVID, study design, diagnostic methods, targeted demographics and duration of follow-up. Higher incidences were reported among hospitalized cases and particularly among adults aged ≥ 65 years43. The exact pathophysiology causing long COVID is still unknown challenging clinicians and researchers alike. Several hypotheses have been presented, each suggesting potential overlapping mechanisms contributing to the persistence of symptoms beyond the acute phase of infection. One hypothesis suggests the presence of a lingering reservoir of SARS-CoV-2 in specific tissues, evading clearance by the immune system and perpetuating ongoing symptoms44. Additionally, immunological dysfunction has been implicated as a potential cause of long COVID symptoms45. Dysregulated immune responses may result in prolonged inflammation and tissue damage, contributing to the chronicity of symptoms experienced by affected individuals. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests a potential link between alterations in the gut microbiota and persistence of COVID-19 symptoms46. Moreover, the reactivation of underlying pathogens has been proposed as another potential mechanism contributing to the prolonged course of illness observed in some individuals47.

We observed a 10% difference in the incidence of long COVID between vaccinated and non-vaccinated dental team members. However, due to the small number of subjects with long COVID, we can not conclusively determine if unvaccinated dental healthcare personnel are more susceptible to suffer from long COVID or experience more severe symptoms. Al-Aly et al.48 conducted a comprehensive analysis using data from the electronic healthcare database of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs examining long COVID symptoms 6-months post infection in 33,940 individuals with a breakthrough COVID infection and several controls without evidence of COVID infection, including contemporary (n = 4,983,491), historical (n = 5,785,273) and vaccinated (n = 2,566,369) controls. The study compared the risk for long COVID symptoms among vaccinated and unvaccinated participants. Participants who were previously vaccinated showed lower risk of developing 24 of the 47 examined symptoms. This risk mitigation became more evident as the care setting changed from non-hospitalized to requiring ICU-admission. Our results confirm established knowledge and are in line with the findings from Al-Aly et al.48. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that while vaccination offers partial protection against the development of long COVID and mortality, it does not guarantee complete immunity. Consequently, relying solely on vaccination to contain the consequences of COVID infection would not be an optimal approach.

Our study focused on a specific occupational cohort. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the prevalence and severity of long COVID among dental healthcare personnel in Germany. As a follow-up investigation, this study has some limitations. The selection of our participants was not representative, because we were bound by the informed consent of participants of our baseline examination. Another larger limitation is the low response rate for the follow-up questionnaire. Furthermore, data on symptoms of long COVID were based on self-reported response and may not be medically confirmed. It was also not possible to accurately calculate the time from infection to onset of symptoms of long COVID and how long it lasted. Despite these limitations, our study offers valuable insights into the prevalence and characteristics of long COVID within the dental healthcare sector in Germany. For following projects, it would be interesting to focus on individuals reporting long COVID symptoms who have received professional medical therapy and to examine its long-term effects.

Conclusion and clinical implication

Our findings indicate that vaccination rates were lower among dental auxiliary personnel compared to dentists. Furthermore, individuals experiencing long COVID symptoms were more frequently dental assistants or dental hygienists than dentists when compared to those without long COVID symptoms. Additionally, our results suggest that dental healthcare personnel are not at a higher risk of experiencing more severe long COVID symptoms than the general population.