In 1976, the year the United States celebrated its bicentennial, Donald J. Trump, thirty, leonine, and three-piece-suited, was chauffeured around Manhattan by an armed laid-off city cop in a silver Cadillac with “DJT” plates, while talking on his hot-shot car phone and making deals. “He could sell sand to the Arabs and refrigerators to the Eskimos,” an architect told the Times. That architect was drawing up plans for a convention center that Trump hoped to build in midtown. Trump called it the “Miracle on 34th Street,” promising a cultural showpiece, with fountains, pools, a giant movie theatre, half a million square feet of exhibition space, and rooftop solar panels.

The Culture Industry: A Centenary Issue

Subscribers get full access. Read the issue »

On the Fourth of July of that red-white-and-blue year, the Tall Ships—a flotilla of more than two hundred vessels from more than a dozen countries—sailed into New York Harbor. Three days later, Trump was in Washington, D.C., presenting to the city’s redevelopment board his plan to build another gargantuan convention center, this one near the U.S. Capitol. Encountering stiff resistance, according to the Evening Star, a visibly “miffed” Trump left the meeting “in a huff.”

The paper did not report whether, before leaving D.C., Trump stopped by the Smithsonian’s Museum of History and Technology to tour its thirty-five-thousand-square-foot bicentennial exhibition, “A Nation of Nations.” Five years in the making, it told the twinned stories of American union and disunion with five thousand objects, from a Ute flute and Muhammad Ali’s boxing gloves to a Klan robe and a sign that read “Japs Keep Out You Rats.” The show aimed to demonstrate how people “came to America, from prehistoric times to the present,” and “how experiences in the new land changed them.”

It is also unknown whether Trump, huffy and miffed, walked along the National Mall to see the Smithsonian’s Bicentennial Festival of American Folklife, the product of years of field work conducted on a scale not seen since the nineteen-thirties. One field worker, for instance, found a Cajun crawfish peeler in Louisiana, and recommended giving her a booth: “She can peel very fast.” The festival featured what organizers described as a “cultural sea” of cooks, dancers, and artisans; musicians, from fife-and-drum bands to Ghanaian gonje players; and a truckers’ “roadeo.” Margaret Mead called it “a people-to-people celebration” that revealed how Americans “have links—through people—to the whole world.”

Neither of Trump’s lavish bicentennial projects came to pass. In September, 1976, a little more than a year after the Trump family business settled a lawsuit alleging that it had refused to rent to Black and Puerto Rican tenants in housing complexes in Brooklyn and Queens, marking their rental applications “C” for “colored” (the company settled without admitting wrongdoing), Trump’s father was arrested in Maryland and briefly jailed, having been charged with housing-code violations in apartments he rented to primarily Black tenants. (The elder Trump pleaded no contest and paid a fine.) And D.J.T., having sought tax abatements and municipal subsidies, lost out in his bids to build convention centers in New York and D.C. The Tall Ships sailed away. The moment passed.

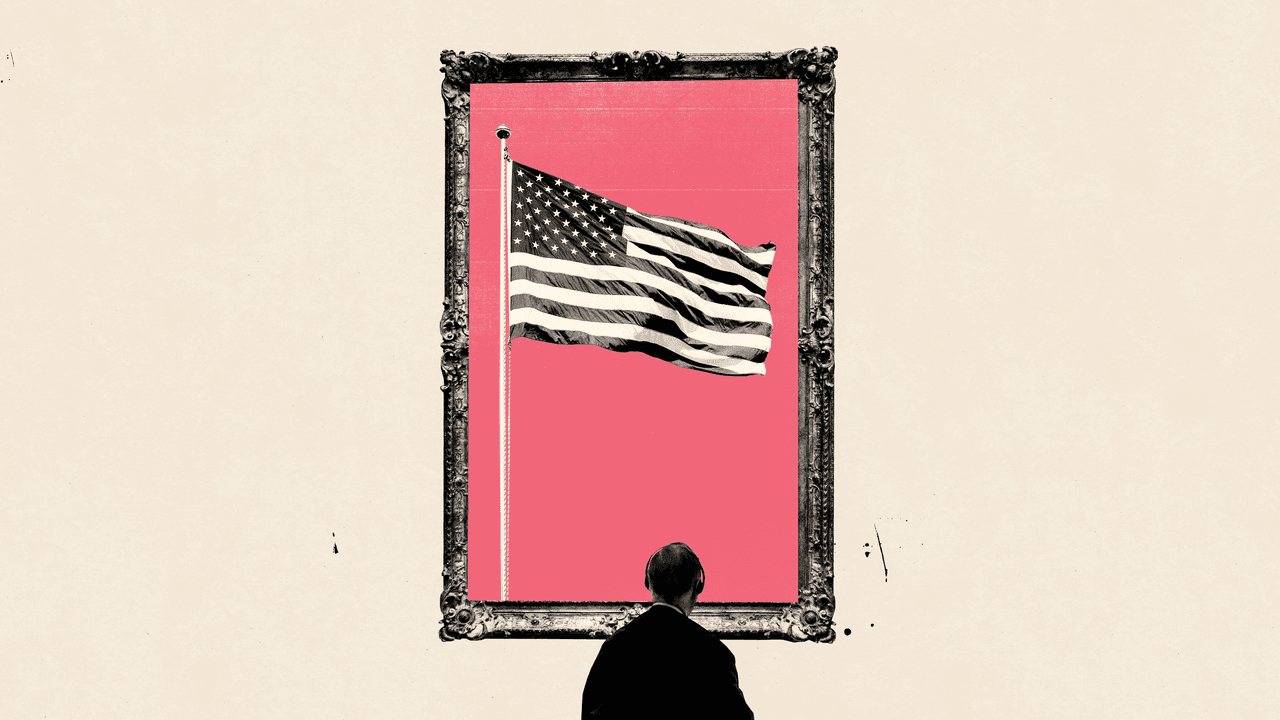

This summer, in advance of next year’s two-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the Trump White House sent a letter to the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, announcing its intention to conduct an extensive review of all semiquincentennial plans. The review will require the museums to provide the President with information including “internal guidelines used in exhibition development”; “exhibition text, wall didactics, websites, educational materials, and digital and social media content”; and “proposed artwork, descriptive placards, exhibition catalogs, event themes, and lists of invited speakers and events.” The Administration, deploying the same strategy that it has used in menacing and extorting universities, did not specify in the letter how it intends to review these materials, or what standards it will apply. It did say that the purpose is to “ensure alignment with the President’s directive to celebrate American exceptionalism, remove divisive or partisan narratives, and restore confidence in our shared cultural institutions,” with “historically accurate, uplifting, and inclusive portrayals of America’s heritage” and especially of “Americanism—the people, principles, and progress that define our nation.” That the President of the United States doesn’t get to decide what is true and what is not is apparently no longer among those principles.

Even before the White House announced the review, the Presidential purge of American cultural institutions had begun. Trump sacked the national archivist, the Librarian of Congress, and the board of the Kennedy Center, and said, on social media, that he had fired the director of the National Portrait Gallery. (He lacks the authority to do so, but she subsequently resigned.) His Administration killed the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, hobbled the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts, and cut federal funding to thousands of state and local programs that support arts and music education for children.

The Smithsonian letter followed an executive order called “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” one of whose directives is “Saving Our Smithsonian,” by “seeking to remove improper ideology” from its museums. The Smithsonian’s twenty-one institutions, whose role in the culture of the nation is invaluable and unparalleled, have had their share of lame exhibits and programs over the years, including a few that have been torridly inflamed by ideological ardor, as is true of any museum or cultural organization. That is the nature of culture. But it’s not in the nature of democracy for the government to intimidate and censor curators who have spent years preparing to do the always difficult and critical work of telling the nation’s story.

“Perhaps our most significant achievement as a nation is the very fact that we are one people,” the Smithsonian proclaimed in a press release in the spring of 1976, at the opening of “A Nation of Nations.” “So many ancient and modern states composed of conflicting tribes, languages, and religious factions have failed to unite and remain whole.” How has this country lasted so long? the Smithsonian asked. “How is it that people representing cultures and traditions of literally every part of the world could come to think of themselves as one nation of Americans?” Those questions wouldn’t pass muster with this White House. They’re still excellent questions, though. How has this lasted so long? ♦