Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the financials of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word’, which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Read more

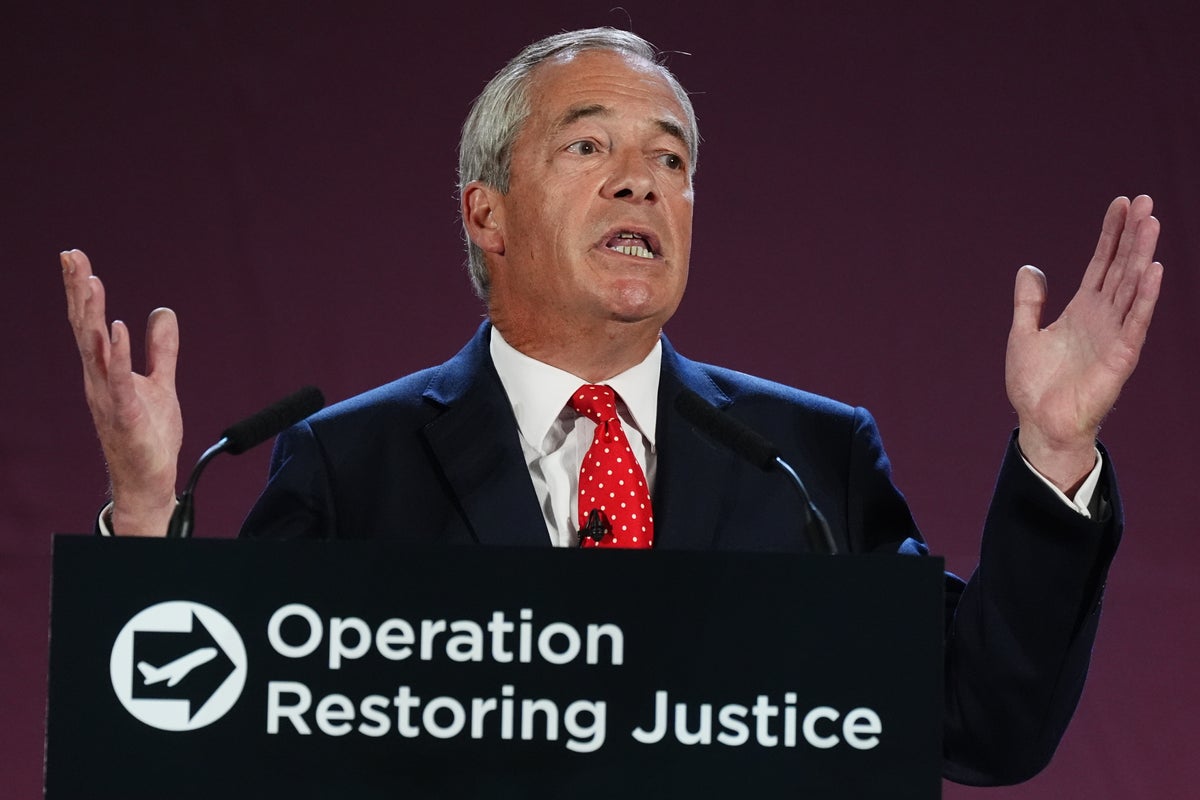

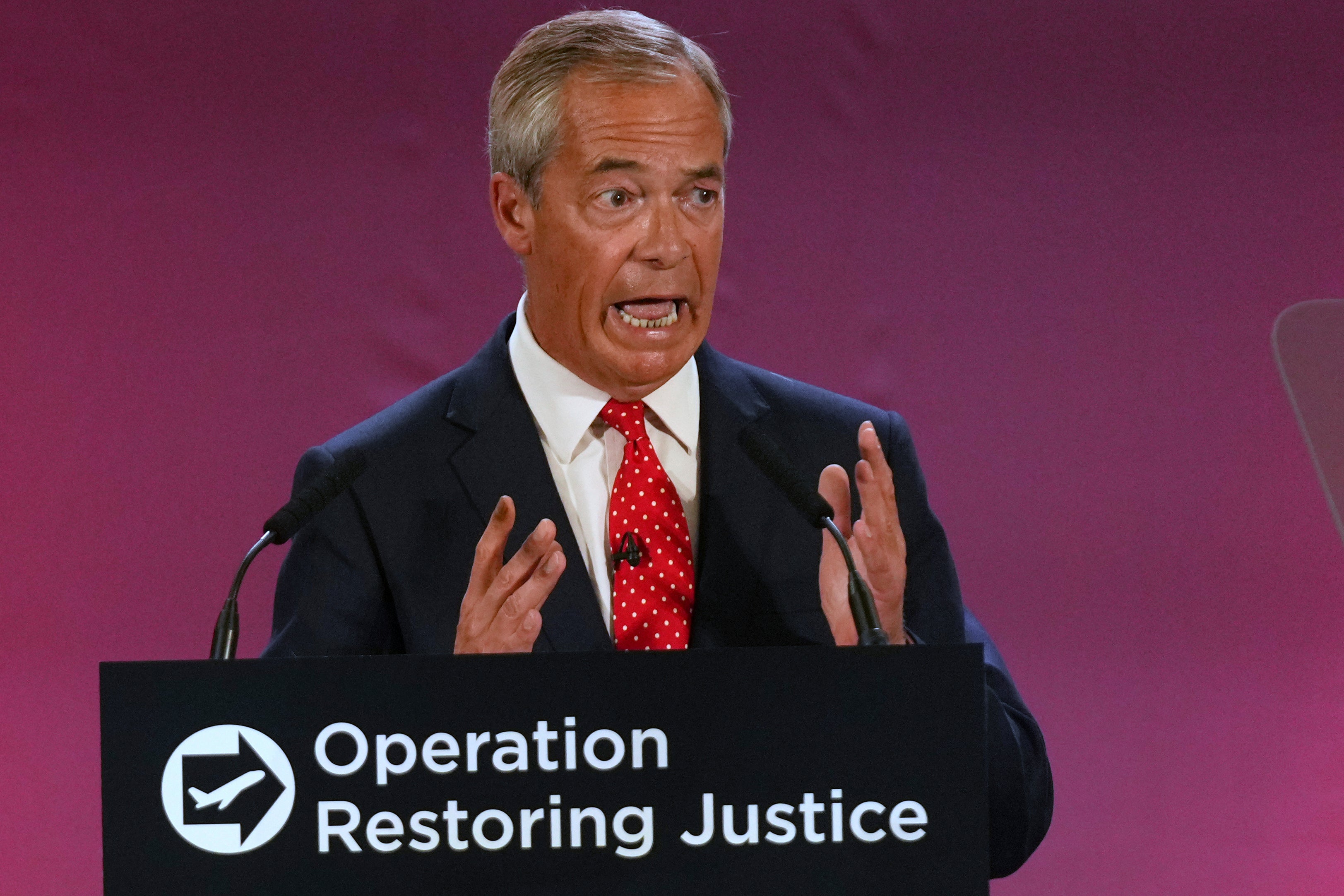

As Nigel Farage stood in front of a giant union flag in an aircraft hangar at Oxford airport, the Reform UK leader laid out his solution to one of British voters’ biggest concerns – illegal migration and the growing number of asylum seekers arriving in the UK on small boats.

But for those who have been listening to Mr Farage for many years in his now long political career, there was something very familiar about today’s announcement. In fact, it was a well-trodden formula for the man who hopes to be Britain’s next prime minister.

What Mr Farage offered was, in fact, a repackaging of what could be termed as the “Brexit formula”. In other words, isolate the UK internationally by withdrawing from foundational global agreements, and then expect the rest of the world to simply do what Britain wants.

This sort of solution worked when Lord Palmerston was able to send a gunboat to sit outside a foreign port in the 19th century, but it is quite a lot more complicated now.

open image in gallery

Farage laid out his mass deportation plans (AP)

The grand plan

Essentially, Farage argues that once he is prime minister, he can force countries like Pakistan, Iran, Syria and Afghanistan to take back thousands of irregular migrants.

Those arriving in the UK illegally will be arrested, detained and then deported, the Reform leader said, as he admitted that he cares more about the frustrated British people than the fate of those who will be persecuted.

He will achieve his goal by withdrawing from the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR), making the UK an outlier along with Russia and Belarus. He will also suspend other international agreements, like the Refugee Convention, for five years.

Zia Yusuf, the party’s former chairman, added that Reform will bring in a watertight law which would mean no judge will be able to block a single enforced departure.

Giving the people what they want

There is no doubt, though, that the polished sales pitch today did offer many voters what they want.

The two traditional main parties have left a gaping hole in the political world by failing to tackle the small boats issue, and the blueprint outlined by Farage on Tuesday leaves Keir Starmer and Tory leader Kemi Badenoch playing catch-up.

Both Labour and the Tories may be criticising Farage’s approach, but they are beginning to copy his policies.

Already the Tories are planning to formally introduce a policy of abandoning the ECHR – a document originally drawn up by Conservatives – while over the weekend, Labour announced plans to water down the “over-interpretation” of human rights by judges.

Government ministers are looking at the polling and listening to the focus groups and know the hardline rhetoric of the Reform UK leader is working.

We saw over the weekend a YouGov poll saying 71 per cent believe Starmer has handled the issue badly, and it remains a key concern among voters, along with the economy.

open image in gallery

Small boats are still crossing the Channel (Getty)

Mr Farage’s most cogent response to his many critics was: “What is being done isn’t working.”

It is very hard to argue with. But will his plan actually work?

Brexit revisited

For those of us still scarred by the political battles that followed the 2016 EU referendum, the naive proposals being outlined by Farage in Oxford had a familiar ring.

Back in 2016, British voters were told that if they voted to leave, then there would be no problem getting a departure deal from the EU and countries would be “lining up” to do trade deals, headed by the United States.

The reality was somewhat different. The departure took four years, two prime ministers and two elections to negotiate, and left the UK in a much weaker position economically. Just to underline the point, Starmer has effectively negotiated the second reset of that original 2020 deal after Rishi Sunak had an effort at a first one in 2023.

As far as trade deals are concerned, it has taken years to get anything with the US, and the deal with Trump is effectively one to lessen the impact of the US president’s tariffs. It took years to get the much-vaunted deal with India, while there are serious questions over the impact of the hastily arranged ones with Australia and New Zealand.

All these are warning notes for any UK government’s future negotiating powers on returns. After all, why has it been so hard to get a deal on returning migrants to France? Because the UK does not have the muscle to force the EU to accept.

open image in gallery

Dominic Grieve outlined the legal barriers to Farage’s deportation plans (PA Archive)

Other problems

Former attorney general Dominic Grieve made it clear that judges could use the British common law vaunted by Farage and his supporters to block deportations.

While Yusuf was confident that no judge could block a deportation, he is no legal expert.

Added to that, there will be the inevitable political upheaval of protests against the draconian measures at a time when Farage himself warned that the UK is on the brink of civil unrest.

Then there will be questions over the fate of those sent back, with even children being packed onto planes.

But the biggest fear will be international isolation. The UK will look like a pariah state withdrawing from human rights and international law. In the short term, it will cancel the agreements with the EU on trade, data sharing and security.

So while Farage was able to trot out the same glib lines that won him the Brexit referendum, there is a danger that the consequences of him actually doing it could be extremely damaging for the country, with the added possibility that he will not even succeed.