Syria wants them back. Germany will pay them to go.

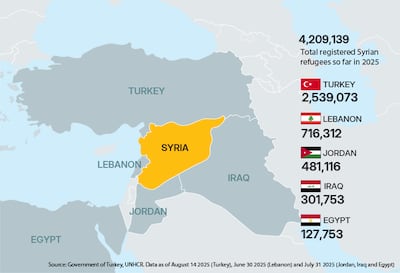

But a generation of one million Syrian refugees is choosing new German roots over the allure of their homeland, with fewer than 2,000 taking up a cash offer to return since the fall of Bashar Al Assad, The National has been told.

Many are marking 10 years in Germany, since the dramatic scenes of 2015, when masses of people, carrying little but the clothes on their backs across Europe, slept at train stations, lit campfires in the streets and persuaded Germans to open their doors.

In interviews, Syrian-Germans say much has changed since. A new government in Berlin preaches border closures and deportations. A new government in Damascus has begun rebuilding from civil war, raising the question of whether Syrians still need asylum in Europe.

Yet many now have deep roots in Germany, with children born and raised there who never knew the old Syria. “We are not between two worlds – we are the bridge that connects them,” one of the 2015 generation, Ahmad Al Hamidi, likes to tell his two children.

Since January, Syrian asylum seekers who return voluntarily have been able to claim travel costs plus €1,000 ($1,160) in “start-up assistance” from the German government. But as of last month, only 1,337 people had done so, Interior Ministry figures obtained by The National show.

A further 227 have had their costs covered by Germany’s 16 state governments, who in turn are reimbursed by Berlin. There are talks on deporting Syrians linked to crime or violence. Right-wing politicians seize on ugly cases to call for “remigration”.

Mr Al Hamidi worries, though, that a purge of bad apples will unsettle the flourishing ones, too. “Someone who lives here, pays taxes here and raises their children here is not a temporary guest,” he said.

‘We can do it’

Jala El Jazairi used to work for a UN refugee agency in Damascus. After Syria’s civil war broke out in 2011, she became a refugee herself.

Once in Germany, she took up work for a refugee council in Potsdam. In the summer of 2015 she witnessed an extraordinary outpouring of sympathy for the hundreds of thousands of people fleeing the Middle East for Europe.

In chaotic scenes, many refugees arrived by boat in Turkey and Greece, then headed north by train or on foot, braving border fences and tear gas. Germans donated clothes and mobilised to put up the new arrivals. There were cheering crowds with “refugees welcome” signs at stations.

“I had more German volunteers coming than I needed at the beginning,” Ms El Jazairi told The National.

Then-chancellor Angela Merkel was the face of Germany’s open-door policy – sometimes literally, with grateful migrants clutching her portrait as they travelled. Her mantra was “wir schaffen das”, meaning “we can do it” or “we’ll manage it”.

Mr Al Hamidi left his birthplace of Aleppo after his home was bombed in the Syrian war, eventually reaching Friedrichshafen in the far south of Germany. He recalls that summer as a time of “euphoria”, when Germany “opened its heart wide”.

It is hard to imagine that euphoria now. But ISIS was on the march in Syria and Iraq, and migrant boats washing up on European shores was a newer and more shocking sight. Mrs Merkel had recently been panned for telling a Palestinian girl that some migrants would have to “go back”, reducing her to tears. And German authorities became overwhelmed, at one point admitting on Twitter, now X, that asylum rules were “effectively no longer being adhered to”.

Some saw a deeper element, an act of atonement for Germany’s past. Mrs Merkel hinted at that, saying she was moved by the opening words of Germany’s post-1945 constitution: “Human dignity is inviolable.” Sigmar Gabriel, her vice chancellor, recognised a Christian impulse. “You can accuse her of some mistakes in handling that challenge in 2015 but certainly not of departing from her inner compass,” he wrote in an essay on Mrs Merkel’s tenure that he shared with The National when she left office.

Whatever its motives, Germany had a practical issue on its hands. How could it handle more than 1.2 million people whose asylum claims were registered in 2015 and 2016? How could it unite Germans with Syrians uprooted from vastly different backgrounds?

“When many of us arrived in 2015, we were individuals – quiet, scattered, often grateful for invisibility or for finding one another while navigating shared uncertainty,” said Khaled Barakeh, a Syrian artist who now has a studio in Berlin.

But the “welcome culture” of 2015, he says, would soon turn out to have conditions attached – an expectation from Germans that their new neighbours would be grateful, bring in useful tax revenue and keep quiet politically.

Integration

Whether Germany did “manage it” is a matter of political debate. The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party surged into parliament at the 2017 election, on an anti-immigrant platform that warned of “Islamic parallel societies”. Others prefer to highlight success stories.

A Syrian view is that sticking together has often brought results. Under the Assad regime “the Syrians had to learn to organise themselves, to protect themselves, to offer services”, Ms El Jazairi said, especially during the war. “This experience that they had there, they brought it with them everywhere they went in Europe.”

One victory for the “Syrian lobby”, she said, was a change to German passport rules that cut the waiting time from eight years to five. Many Syrians have gone down that road: more than 80,000 became German citizens in 2024, far more than any other nationality. Syrians “often apply for citizenship as soon as they meet the conditions”, Germany’s statistics office noted in June.

Mr Al Hamidi, one of those new citizens, also praises the Syrian community spirit. As more refugees arrived, Syrians already in Germany “took up a key role, not just as interpreters but also as mentors, neighbours and members of societies”, he said.

He sees progress, too, in the job market, where Syrians were often held back by a lack of language skills or recognised qualifications. “The German labour market is like a castle with many doors and not all of them open easily,” said Mr Al Hamidi, a lawyer. “The labour market needs us and we need fair opportunities.”

Economists say Syrians are vital for plugging labour shortages in an ageing German population. The AfD likes to mock that idea, often using “skilled workers” as sardonic code for migrants involved in crime.

From 2020 onwards, the number of Syrian asylum seekers climbed again, arriving either from their battered country or from limbo in refugee camps. Some arrive in Europe unable to read their own language, never mind German.

“A lot of people came from Syria with a literacy problem – they couldn’t write and read,” Ms El Jazairi said. “The level of literacy in Syria is better than other countries, like Afghanistan, for example, but still it was a challenge.” She helped set up courses for mothers and carers with little time for German lessons.

Even while Mr Al Assad was still in power, Germany was eyeing up ways to return the poorly integrated and those denied asylum. Most of the 2015 intake were granted three-year refugee status. More recent arrivals have been given only one year of “subsidiary protection” because they were not at individual risk.

Mr Barakeh, the artist in Berlin, says the war in Gaza has also shrunk the “ideological space to manoeuvre” for refugees, with Germany’s always twitchy anti-Semitism radar on particularly high alert. German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier was criticised for telling Arabs in Germany to distance themselves from Hamas.

“Integration is no longer imagined as a two-way process of mutual transformation but as an obligation to assimilate, to become palatable,” Mr Barakeh said. “We are all painted with the same brush as if we are one thing, without looking into our complex individual being.”

There is a “gap between what Germany wants Syrians to be – integrated, post-conflict, grateful – and what we know ourselves to be”, namely survivors of an unresolved war and bearers of stories the West has grown tired of hearing, he added.

The future

Some Syrians celebrated on German streets when Mr Al Assad was overthrown in December. But he had barely begun his exile in Russia before European politicians were discussing their return.

Asylum claims were frozen and most are still in limbo while Germany monitors developments. While only 70 Syrians have been rejected outright so far this year, more than 51,000 are awaiting a decision. Having resumed deportations to Afghanistan, Germany is studying its options for Syria, and even those with a secure footing wonder about the future.

“The discussion about deportations affects a small minority and it must not lead to millions of people having to wonder if they really belong,” said Mr Al Hamidi. He sees Syrians as “part of the solution” to Germany’s economic problems. “We bring our energy, our education, our children – Germany gives us security, opportunities and community,” he said.

The German government that took office in May has explicitly turned its back on the spirit of 2015. Chancellor Friedrich Merz, an old rival of Mrs Merkel, says his Christian Democratic Union party “made mistakes” that year. Alexander Dobrindt, the current Interior Minister, withdrew a Merkel-era instruction that police should not turn away asylum seekers at the border.

The Syrian government under President Ahmad Al Shara is meanwhile striking eye-catching investment deals with Gulf countries and has encouraged refugees to come home. But its efforts to rebuild have been marred by sectarian violence and regional power struggles.

At least one man, Youssef Al Labbad, was allegedly tortured and killed on his return from Germany. A humanitarian official who visited Syria last week was dismayed to find that people who returned “brimming with ideas” had “hardly any assistance to help people rebuild lives, homes and livelihoods”.

Almost one in four Syrians in Germany are too young to have known life before the civil war, analysis by The National revealed last year. Syrian television has reported on people struggling to register their children once they return home.

One 55-year-old resident of Damascus predicted that most exiles who come back to Syria would “consider it a temporary return and will return to the countries they came from, because they have adapted to life in European countries and Syria has become, for them, a visitor’s destination only.

“First, in their opinion, the country is currently unstable, and second, they like life in countries that grant people and citizens full rights,” he said. “This is my opinion, I could be wrong.”

Another Syrian exile, a human rights researcher, arrived in France in May 2024, months before the Assad regime fell. Will he go back? “Of course I want to, and I want to go back to all my memories and my family,” he said.

His sister’s husband was executed under the old regime in 2013. The new authorities “haven’t shown in their behaviour that they represent a danger to rights researchers or journalists,” he said. “Will the situation stay that way? I don’t know.”

Then there is the economic situation. From Europe the researcher sends between $400 and $500 a month to relatives who earn far less in Syria.

“If I go back to Syria, I can’t cover expenses for my family and my family is my responsibility,” he said. “Most of them don’t have any work, meanwhile me here in Europe, I can work. And I can send them a large chunk of my income so they can live.”

Many more are still in limbo elsewhere, in countries such as Turkey and Lebanon. Malik, a bazaar worker in the Turkish city of Gaziantep who is originally from Aleppo province, said: “I was going to go to Syria but there is no work there now. I will stay here working. When things improve in Syria, I will go.”

In Germany, the verdict so far is clear. Although the 1,564 people who have taken the cash offer to return to Syria may not be the whole number – others could have slipped out quietly – most are staying into a second decade of the German-Syrian story that began in 2015.

Mr Barakeh plans to keep one foot in each country. His projects include a first Syrian Biennale, and an initiative called Little Syria in Jaramana, near Damascus, that aims to be a model for post-Assad civic life. Back in Germany, he wants to help people resist deportations through legal advocacy.

“The logic is quite coercive,” he said. “If Damascus is no longer a war zone, why are you still here?

“Many Syrians live in limbo – not because they haven’t rebuilt their lives in Germany but because Germany at any point might decide arbitrarily that Syria is ‘safe enough’.”

Pharaoh’s curse

British aristocrat Lord Carnarvon, who funded the expedition to find the Tutankhamun tomb, died in a Cairo hotel four months after the crypt was opened.

He had been in poor health for many years after a car crash, and a mosquito bite made worse by a shaving cut led to blood poisoning and pneumonia.

Reports at the time said Lord Carnarvon suffered from “pain as the inflammation affected the nasal passages and eyes”.

Decades later, scientists contended he had died of aspergillosis after inhaling spores of the fungus aspergillus in the tomb, which can lie dormant for months. The fact several others who entered were also found dead withiin a short time led to the myth of the curse.

The specs

Engine: 5.2-litre V10

Power: 640hp at 8,000rpm

Torque: 565Nm at 6,500rpm

Transmission: 7-speed dual-clutch auto

Price: From Dh1 million

On sale: Q3 or Q4 2022

GAC GS8 Specs

Engine: 2.0-litre 4cyl turbo

Power: 248hp at 5,200rpm

Torque: 400Nm at 1,750-4,000rpm

Transmission: 8-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 9.1L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh149,900

Ziina users can donate to relief efforts in Beirut

Ziina users will be able to use the app to help relief efforts in Beirut, which has been left reeling after an August blast caused an estimated $15 billion in damage and left thousands homeless. Ziina has partnered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to raise money for the Lebanese capital, co-founder Faisal Toukan says. “As of October 1, the UNHCR has the first certified badge on Ziina and is automatically part of user’s top friends’ list during this campaign. Users can now donate any amount to the Beirut relief with two clicks. The money raised will go towards rebuilding houses for the families that were impacted by the explosion.”

Specs

Engine: Dual-motor all-wheel-drive electric

Range: Up to 610km

Power: 905hp

Torque: 985Nm

Price: From Dh439,000

Available: Now

The specs

AT4 Ultimate, as tested

Engine: 6.2-litre V8

Power: 420hp

Torque: 623Nm

Transmission: 10-speed automatic

Price: From Dh330,800 (Elevation: Dh236,400; AT4: Dh286,800; Denali: Dh345,800)

On sale: Now